Leafy rushfoil shivered in the breeze, the morning sun bounced off the murky depths of a nearby watering hole, and my legs ached from crouching, and waiting. “Here they come,” the keeper eventually whispered.

I glanced up, following the direction of his gaze to the well-trod, winding trail ahead. I imagined I would feel tremors and be deafened by the sounds of trumpeting, as I witnessed the world’s biggest terrestrial beasts crashing through the bush.

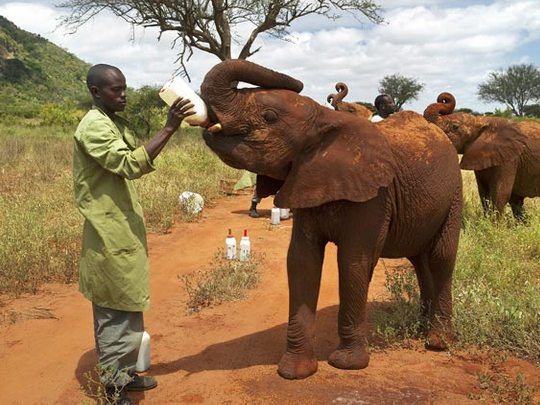

Instead, the warm Kenyan air was gently filled with the playful rumbling noises of happy infants, a herd of ten baby elephants, their big brown ears flapping as they trundled down the path towards us. Under the fragmented shade of the acacia trees, I leaned down to stroke one of the wrinkly creatures.

Barsilinga’s skin was rough despite his youth, and interspersed with small wiry black hairs. His clumsy trunk moved constantly around me, exploring the new and unfamiliar scent. Whether it was approval of my new French perfume, Chance, or not, Barsilinga left a long gooey trail of elephant mucus all the way up my arm.

I took the act as endorsement, a sign that chance had indeed intervened in this little calf’s life. A violent encounter with ruthless ivory poachers left his mother riddled with bullets and could have dimmed the lights forever of the deep brown eyes that were blinking up at me now.

Ivory poaching is the principal reason the orphaned elephants have found their way to the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. Most have lost their mothers and herds at the hands of a brutal, violent trade supplying an insatiable demand across Asia. Considerable work to address the issue is being carried out by governments and non-governmental organisations across Africa, but if more is not done, and quickly, these much-loved animals may soon be lost forever. It would be a travesty, especially as Amboseli Trust for Elephants’ research associate Dr Vicki Fishlock, says, “E is for the elephant in every child’s alphabet book across the globe for a reason.”

Extinct by 2020?

Africa has found itself embroiled in a new form of annihilation, one that could be termed ‘elephant genocide’. Annually, tens of thousands of these intrinsically ‘human’ animals are being wiped out at the hands of ivory poachers.

Experts say demand for the coveted tusks has led to poaching levels unseen since an international ban on ivory trade took effect in 1989. Today the continent is home to an estimated 472,000 elephants, a slim number when compared to the estimated 5 million in existence some 60 years ago.

“Poaching is worse now across the continent than it ever has been,” says Dr Fishlock. “In five years the elephant population has halved in central Africa… 2011 was the worst year for ivory seizures we have ever seen. It looks like this year is going to be even worse.”

Last year, according to the New York Times, 38.8 tonnes of ivory, or the equivalent of tusks from more than 4,000 dead elephants, was uncovered, breaking the record for the amount of illegal ivory seized worldwide. The figures compare sharply to the year before when hauls weighing a little under 10 tonnes were seized.

The escalating demand for ivory and its ever-increasing worth has led to a severe depletion in elephant numbers. In Tanzania, officials have documented a 43 per cent decline in the country’s elephant population in the last three years alone; with authorities saying 30 elephants a day are being slaughtered. And, Fishlock points out, “that’s just Tanzania. We don’t even know what’s happening in parts of central Africa”. With such unprecedented figures reflecting the state of elephant populations across Africa, the possibility of extinction by 2020 could rapidly become a grave reality.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, illegal wildlife trade, which is valued at between $8 billion and $10 billion (Dh29 billion and Dh37 billion) a year, ranks as the fifth most profitable illicit activity across the globe behind drugs, guns, human trafficking and counterfeit goods. Last month, in a little under two weeks, police in Africa and Hong Kong seized elephant tusks worth millions of dollars. The Hong Kong consignment (worth $3.4 million), destined for the Chinese black market from Kenya and Tanzania, was the largest seizure ever in the history of China. Approximately 600 African elephants died to make up the 3.8-tonne haul, but experts say these kinds of numbers only scratch the surface, not least because of the illicit nature of the trade. Most evidence attributes the rise in the ever-growing demand for ivory to the Far East. China recently overtook Japan as the world’s largest ivory consumer and a recent report in the New York Times suggests as much as 70 per cent of illegal consignments are headed to the East Asian country.

China’s recent economic boom has seen a vast widening of its affluent middle class and although it has a long history of coveting ivory, this is the first time so many have had the means to own the sought-after commodity.

Soaring market value

The cycle of demand versus availability has sent market prices spiralling; today one kilo of ivory can have a price tag of between $1,000 and $1,500 on the Asian market. A staggering figure when an elephant tusk can weigh up to 10 kilograms.

For millennia ivory has been a symbol of wealth in the Far East. Traditionally it was carved into delicate, ornate artefacts or transformed into tools, buckles and jewels for the wealthy. Prior to the introduction of plastic, ivory was often the chosen material for everyday objects such as chopsticks, dominoes and hair accessories. To this day, mass-market trinkets and jewellery can be found across Asia, while in Japan, ivory remains the popular choice for ‘hankos’, or name seals, which enable the owner to uniquely “sign” documents.

More recently it was consistently used to make piano keys, with Steinway famously using ivory until 1982. Alongside ornamentation, many in the Far East believe tusks have medicinal properties to cure fevers and other illnesses, but as veteran elephant expert Dr Dame Daphne Sheldrick from Kenya’s David Sheldrick Trust for Elephants explains, “its just a myth, there is no scientific proof. It is just keratin, if people chewed their fingernails they would get the same thing.”

The task of educating the Asian market, whose belief in myth and tradition is a deeply ingrained cultural phenomenon, is gargantuan. The Chinese word for ivory translates as “elephant tooth” and many believe that, as in humans, these teeth simply fall out. James Isiche of the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) told the Wall Street Journal that a recent survey suggests “70 per cent of Chinese consumers did not know that elephants were killed for ivory”.

Many organisations are working hard to raise awareness that retrieving ivory from elephants is horrifying and that poachers shoot elephants with automatic weapons and hack off the tusks with axes or chainsaws. But, as Dr Fishlock says, “one conservationist education group in China has programmes running in 250,000 schools across China and they consider that isn’t nearly enough to raise awareness”.

Perhaps Yao Ming, the former NBA star and recent Olympic commentator on Chinese television, will prompt change amongst the younger generations. Earlier this year he travelled to Kenya with charities Save the Elephants and WildAid. The campaign and public service announcements reached one billion people a week assisted by his popular blog where, alongside images from his highly publicised trip, he added, ““I’m told the main destination for illegal ivory is China.”

Underworld links

Until the message hits home, the poaching of elephant tusks is big business. The organisation, transport and smuggling of ivory out of Africa is undertaken, according to many, by organised crime units, a longtime supposition that is becoming increasingly difficult to deny. The methods and the scale of trafficking are unlikely to have had the success they have had without the assistance of both the underworld and corrupt officials.

Huge stashes of ivory are making their way across porous borders into port countries such as Kenya, where they are then shipped in boxes purporting to contain scrap plastic, anchovies or beans, to Asia.

Wealthy crime syndicates have the financial means to easily bribe government officials from economically crippled African countries or intimidate poorly paid customs officials and law enforcement officers. They also have the disposable money to lure residents of poverty-stricken rural areas into the trade and a cash payment offer for a single tusk can be worth ten times a local’s annual salary.

As Dr Fishlock points out, “It’s not just a simple case of people poaching to supplement their livelihood, we’re discovering that the people doing the poaching aren’t trying to pay their child’s school fees or feed their family, they’re doing it for profit.”

Poachers supported by sophisticated criminal gangs are now annihilating entire herds. Earlier this year more than 300 elephants were slaughtered by armed horsemen in the Bouba Ndjida National Park in northern Cameroon, with reports that they hacked off the tusks while the animals were still alive. Within the same month another mass slaying took place in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Here helicopters swooped over a herd of 22 terrified elephants mowing them down one by one with AK-47 rifles, sending panicked babies rushing to the cover of the bush. According to experts, the accuracy and precision of the shots, alongside the use of helicopters, indicates the work of professionals.

Ben Janse van Rensburg, a member of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Cites) says, “The biggest challenge is that in the last few years there has been a big shift from your ordinary poachers to your organised crime groups.’’

Casualties of conflict

The problem has also been exacerbated by conflict in the continent and the overspill of seasoned fighters from war-torn areas like Sudan. As Dame Daphne explains, “Kenya is surrounded by countries in conflict… the country has been invaded by those who have been displaced in their own countries, Somalis, Sudanese, and all of these people are making a living out of ivory”.

Elephants seem to have become the latest casualty of conflict. Journalist Jeffrey Gettleman points out in a New York Times article in September that the recent upsurge in the ivory trade is comparable to that of blood diamonds, “Ivory, it seems,” he writes “is the latest conflict resource in Africa, dragged out of remote battle zones, easily converted into cash and now fuelling conflicts across the continent.”

On the ground the realities of poaching leave not only elephants at risk but also those protecting them. Wildlife wardens in the field put their lives on the line to stem the poaching epidemic and losses amongst anti-poaching teams are a reality.

Protecting wildlife in national parks means coming face to face with the likes of Somalia’s Al Shabab militants and Uganda’s LRA, both of whom are funding their wars with blood ivory.

Last month, rebels in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Virunga National Park assassinated two rangers and a soldier, taking the toll to 150 of those killed there since 1996. One ranger, Paluku Matembela, left behind a six-month-old son and a 14-year-old daughter, both of whom are now orphans having lost their mother six months earlier. Finding a solution to prevent elephant extinction is a fiercely disputed one. Countries across the African continent are at loggerheads depending on their elephant populations.

In South Africa, in contrast to the depleting numbers elsewhere, elephants have grown in number to approximately 20,000. Officials there say they are suffering from over-population and complain that elephants, which can devour 140 kilograms of vegetation each on a daily basis, have turned large swaths of woodland into grassland.

In 2008 South Africa announced it would lift its 1994 ban on elephant culling although it has not yet come into effect much to the relief of elephant-loving conservationists. “There are too many humans in the world but no one talks of culling the human population, although we are destroying the planet,” Dame Daphne retorts.

Lopsided elephant figures across the continent have divided not only governments but also laws enacted by Cites. In 1997, when elephant populations were increasing, despite the best efforts of charities, Cites allowed the sale of 40 tonnes of stockpiled ivory from Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe to Japan as a one-off. Many predicted a surge in poaching and figures from the following years proved them right.

In 2002 the same three countries, along with South Africa, received permission to sell another 60 tonnes of stockpiled ivory and again in 2007, the amount was elevated from 60 to 110 tonnes to generate income for the African states. Many have argued that selling stockpiles fuels further demand for ivory and allows illegal ivory to be laundered through the system, and statistics tend to support these arguments.

The death of elephants rose to nearly 10 per cent and ivory prices ballooned. As IFAW’s Isiche stated at the time, “the correlation between this rise in elephant poaching and the one-off sale of stockpiles by Cites can no longer be ignored”.

If elephants are to be protected from poachers, then, Dame Daphne says, “it has to be banned totally by Cites and the international community has to get involved, its now beyond the capacity of local countries to control.”