Sterile mosquitoes released in China to fight dengue

Scientists carry out trial in southern province of Guangdong aimed at reducing population of insects that carry the disease

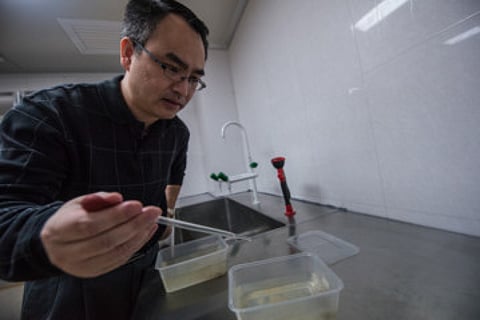

This spring, a team of scientists has been driving around a small island in Guangzhou, southern China, releasing more than half a million mosquitoes from plastic pots on board trucks.

Rather than chasing the researchers away, families have welcomed their incursion: “Some residents have even asked to get mosquitoes from us to release in their own home,” said Xi Zhiyong of Michigan State University, who heads the project.

The sight of the insects might set the skin crawling, but people know the alternative could be worse: this is one of several innovative attempts to tackle dengue fever by diluting the mosquito population with insects that don’t carry the disease.

The mosquito-borne sickness causes pain so agonising it is also known as “breakbone disease” and last year saw China’s worst outbreak in two decades, with more than 47,000 cases, almost all in Guangdong province.

Catch one strain and you will be immune to the virus in future — but if bitten by a mosquito carrying another of the strains, you are more likely to develop severe dengue, also known as dengue haemorrhagic fever. No vaccine or treatment is available and recently it has caused about 22,000 deaths a year worldwide, mostly among children.

Before 1970, only nine countries had severe dengue epidemics; now it is endemic in more than 100 countries. Two-fifths of the global population — across Africa, Asia and Latin America — could be at risk. In the past few years, dengue has reached the United States and Europe.

Yang Zhicong, deputy director of Guangzhou’s centre for disease control and prevention, said authorities had hired anti-mosquito squads and quarantined dengue patients.

But “prevention and control needs international cooperation to make it effective”, warned Chen Xiaoguang, an expert in tropical infectious diseases at Southern Medical University in Guangzhou. Xi and his colleagues have released mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia bacteria, which make the males sterile and limit the insects’ ability to carry dengue.

Last year’s outbreak has helped persuade residents to embrace the pilot scheme, as has Xi’s willingness to plunge his hand into mosquito pots to prove that the males they are releasing do not bite. And while the Chinese government has not approved the release of genetically modified creatures, it accepted this trial because Wolbachia occurs naturally in many insects.

In the first phase, the team aims to reduce the mosquito population, as sterile males breed with wild females. In the second, Wolbachia-infected females — “very few”, Xi promised — will be released to replace the wild, dengue-transmitting population, so mosquitoes from other areas face competition if they try to move in.

“The final outcome in the release site will be that, firstly, there will be few mosquitoes biting people, and secondly, these mosquitoes are resistant to dengue virus,” he predicted.

Dengue has been overlooked by governments and aid donors, said Dr Raman Velayudhan, of WHO’s department of control for neglected tropical diseases. “In terms of the number of people who fall sick, dengue and malaria are very similar. Dengue affects 128 countries; malaria 97. The neglect I think comes because dengue doesn’t kill as many people.”

Annelies Wilder-Smith, coordinator of the Dengue Tools initiative and professor of infectious diseases at the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine in Singapore, said it had also received little attention because it had not affected wealthier or Western countries until recently. “You are talking about 100 million symptomatic cases [annually] ... It poses an incredible burden on healthcare systems and also carries a high economic burden.”

One report estimated that the disease cost India alone £700 million (Dh3.9 billion) annually. More worryingly, noted Velayudhan, “it is a problem of the future: it is a disease of urbanisation — and by 2030, we will have 70 per cent urbanisation globally. We have more and more urban centres and those are the cradles of dengue,” he warned.

Global warming and globalisation are also a factor. Mosquitoes flourish in warmer temperatures and lay eggs in water. Though they fly a few hundred metres at most, their dried eggs can travel across the ocean in cargo and rehydrate months later; and as people travel, they take the illness to new locations, where local mosquitoes can transmit the virus to others.

Now the fightback has begun. Three years ago, the WHO introduced its first strategy to tackle the disease, aiming to cut the number of cases by at least 25 per cent and deaths by at least 50 per cent (from 2010) by 2020. Despite several major outbreaks, Velayudhan said the number of deaths had already fallen by 20 per cent.

And after years of research, experts hope that innovative anti-dengue measures — including population control techniques, a vaccine and treatments — will soon be available. “It’s really an exciting time,” said Wilder-Smith. “I hope that there will be more funding — there’s exponential growth in dengue research.”

Pharmaceutical company Sanofi Pasteur has completed large-scale phase three trials for its vaccine and is filing for registration in several Asian and Latin American countries; it has already started production, so could deliver the first doses by the end of the year. But the vaccine is only partially effective, meaning that its impact will be limited even if it is rolled out widely.

Meanwhile, the disease will continue to affect new countries, warn the experts, with local transmission spreading in Europe and the US. “In Florida they say it’s already established. In Madeira there was a big dengue outbreak in 2012 with more than 2,000 cases,” said Wilder-Smith.

Potential methods

“There’s no single magic bullet. Even if we had a vaccine with close to 100 per cent efficacy, we would never achieve total coverage,” said Wilder-Smith. So controlling the mosquitoes that transmit dengue will remain important, but novel approaches to this side of the problem are still at the research stage. “They are not out there for policymakers to roll out yet,” she noted.

Vector control

The aim is to reduce the population of dengue-spreading mosquitoes. In Singapore, for instance, authorities have urged residents to adopt the “mozzie wipeout” routine, which includes changing water in vases and bowls on alternate days and adding insecticide to roof gutters monthly.

Newer methods include genetically modifying mosquitoes or infecting them with Wolbachia. “Traditional methods of insecticide spraying are expensive, difficult to do and often not very effective,” said Scott O’Neill, dean of science at Monash University and head of the global Eliminate Dengue initiative, which has released Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes in Australia, Vietnam, Brazil and Indonesia in a similar programme to Xi Zhiyong’s. It has just embarked on its first citywide pilot, in Townsville, Queensland.

O’Neill hopes there could be a global spread of the programme in five years. “It would be a challenge, but we definitely think it’s achievable — think about the distribution of impregnated bed nets and how successful it has been in households across sub-Saharan Africa,” he said. “Our expectation of the cost is that it would be much less than insecticides.”

But as Xi pointed out, individuals buy insecticides to protect their own home. Adopting schemes that depend on community-wide changes will almost certainly require government funding.

Protection

At its most basic, this can mean wearing insect repellent and covering up. But after decades of research, it seems that a vaccine may be close to introduction. Sanofi Pasteur has completed phase-three trials involving more than 30,000 people in Asian, Latin America and the Caribbean and is applying for licensing in several countries.

The good news is that the vaccine covers all four strains of the disease, showed protection against severe dengue and a reduction in the risk of hospitalisation. The bad news is that it is only partially effective. “We cannot discontinue dengue vaccine development with this kind of vaccine — but the Sanofi Pasteur vaccine is the only one we have,” said Wilder-Smith.

“The question is: should a partially effective vaccine be rolled out, or should we wait for something better? If you are a country with a very high burden, even 50 per cent reduction may justify introduction. If you are a low burden country, most policymakers will decide not to continue because the benefits are not as measurable.”

Some have raised concerns that the partial efficacy of the vaccine could lead to increased problems in the long run. “Sanofi Pasteur has had years of observation and there were no adverse events seen after a longer time period,” noted Wilder-Smith.

But while experts do not anticipate such problems in the long run, “we can’t rule them out because of antibody enhancement. We don’t know whether the antibodies with the vaccine are identical to the antibodies produced by the disease; they’re probably not totally the same,” she said.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox