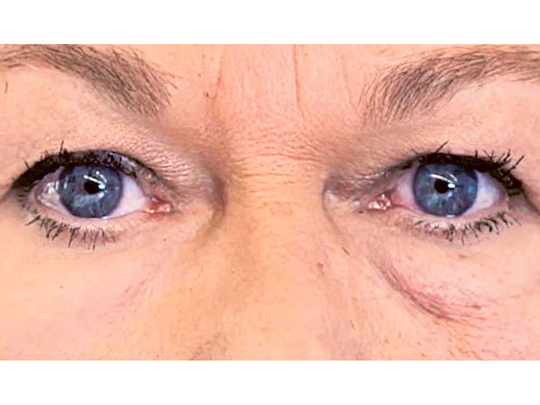

Even if you try to love the skin you’re in, chances are that you’d make a few tweaks if you could. But what if instead of plastic surgery or questionable cosmetic potions, you could slather on a second skin that eliminated some of those imperfections? Scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard say that the material they’ve developed can seamlessly smooth the appearance of wrinkles and sagging under the eye. And the same “second skin” could have a wide range of medical applications.

The material might sound familiar: initially developed by skin and haircare company Living Proof, the so-called Strateris platform (now under development with a spin-off company called Olivo Labs) was briefly introduced to a small number of dermatology practices in 2014. At the time, it was marketed solely as a under-eye solution — and it’s no longer available for sale. But a paper published earlier this month in “Nature Materials” tests the limits of the unique skin coating, and the researchers involved say it could actually find its best use in patients with severe skin problems such as eczema or psoriasis, which can both cause extremely dry and itchy skin.

That’s because the system — which goes on the skin in two steps, each a simple application of a gel or cream — locks in moisture as well as the thickest, stickiest ointments can. And instead of washing off or becoming less effective as it smears away on to clothing and other surfaces, the second skin can stay on for at least 24 hours, or until users deliberately rub and peel it off. In tests of 25 users, just two had visible “edges” after 16 hours of wear.

Study co-author Barbara A. Gilchrest, acting president of the American Skin Association, said that she hopes to see the material used to treat eczema and psoriasis, which can be debilitatingly uncomfortable in the elderly. These conditions largely come down to the skin’s failure as a barrier between the body and the outside world, she explained, and artificially supporting that barrier with a new layer of “skin” could keep patients more comfortable.

“The only thing we have to offer people at present is a heavy moisturiser, which does work temporarily ... but it’s not at all ideal,” Gilchrest said. “This heavy layer of moisturiser looks and feels greasy. It gets all over your clothes and bedclothes. It’s just really not very good.”

The new material acts more like skin than like a layer of ointment. It contains a chemical structure known as siloxane (a chain of alternating atoms of silicon and oxygen) that assembles itself into an interlocked network when exposed to another chemical compound. The siloxane slides on smooth, then hardens when the second layer is added. Still, it retains impressive elasticity: it can return to its original state after being stretched more than 250 per cent, while natural skin can only be elongated about 180 per cent. And the second skin returned to its smooth state much faster than saggy under-eye skin or “invisible” wound coverings currently available on the market. The researchers involved cycled through 100 siloxane-based polymers to find one with such desirable properties. The study reports no negative effects in the test subjects, and Gilchrest claims that the subjects used to test the wrinkle-fighting powers of the polymer absolutely loved it.

In the future, the polymer could even contain medications that otherwise might not properly penetrate the skin.

“Ointments have the same problem that greasy moisturisers have,” Gilchrest explained. Patients often opt to get their topical medications in cream form — ones that slide on and absorb quickly like lotions — to avoid having sticky ointments on their skin. But these don’t usually work as well.

“Having something that would be practical and stay on and be acceptable to patients as a way of delivering more medication where it’s needed could open up a whole area in which we could provide more effective, more practical, more pleasant treatments,” she said.

The researchers wouldn’t comment on projected costs, and when it was offered in limited quantities in 2014 the second skin cost a hefty $500 (Dh1,837) per month for a supply intended to hide under-eye wrinkles. One shudders to think at what it would cost to slather the stuff all over an itchy body, but a scale-up in production could presumably cut the cost. And if the technology makes its way into prescription pharmaceutical products, insurance companies may foot part of the bill for patients in need.

Study author Amir Nashat, who received his PhD in chemical engineering under fellow study author Robert Langer of MIT and who has been involved with Living Proof since its early days, confirmed that Olivo will be focused on medical applications — and primarily skin conditions such as eczema — for the time being. The lab expects to have clinical data within the next year.

“We do know that there are beauty and cosmetic and wellness applications, and over time we’ll explore and commercialise those as well,” Nashat said.

Gilchrest doesn’t think the cosmetic applications are anything to wrinkle your nose at: the under-eye area produces some of the most visibly prominent signs of aging, and large bags make you seem tired and disinterested. Humans are superficial beasts.

“The truth is that appearance matters to people,” Gilchrest said, explaining that there isn’t a particularly effective alternative to surgical intervention on the market. “There are a number of things on the market that work by hydrating the skin, but they have a largely transitive effect,” she said. “People use these things religiously.”

Indeed, one recent survey projected that the global anti-ageing market would be worth $191.7 billion by 2019. But studies have found many of the lotions and potions to be woefully ineffective.

The new second skin seems to provide a more notable, immediate effect — but whether it will ever be an affordable beauty aide is another matter entirely. For now it can’t be layered on or under make-up, which would likely turn off a large portion of its cosmetic customer base. If Olivo Labs moves the product back into the beauty world, material scientists may have to tweak the formula to make it suitable for use with make-up — or just create entirely new make-up products to go with it.

–Washington Post