Haji Noor Deen is the first Chinese person to be awarded the Certificate of Arabic Calligrapher in Egypt

On first impression, the calligraphic work Haji Noor Deen is showing me on his laptop appears to be in Chinese. On closer inspection, however, I have to scratch my head as the lettering turns out to be Arabic script. “It looks like Chinese but it is Arabic. Asma ul Husna [99 beautiful names of Allah] has so much Alif Laam [Arabic letters.]” he says.

The calligraphy drawn by this world renowned artist from China very much revolves around an Islamic theme. “Al Bari, Al Jabbar. Al Mutakabbir, Al Khaliq...” he says, reading out to me some of the 99 names of Allah. In 2005 Deen’s work The Ninety Nine names of Allah was acquired by the British Museum for permanent display at their Islamic Gallery. Deen has travelled to many parts of the world to teach and exhibit his work. He has been frequently included in the list of the Top 500 Most Influential Muslims between 2009-2015.

Deen was born in 1963 in eastern China’s Shandong Province. He started learning Arabic calligraphy at the mosque when he was 18 years old. “At that time Islamic knowledge, like Quran or Hadith, should be copied by right hand. From that time [I] started learning calligraphy,” he says. In the 1990s he lived in Cairo, where he studied calligraphy. In 1997 he became the first Chinese person to be awarded the Certificate of Arabic Calligrapher in Egypt. Later he travelled to Turkey where “he followed the most famous Arabic calligrapher” — being the first Chinese to study under the talented Shaikh Hassan Jalabi and Dawoud Baktash.

Chinese calligraphy tends to be read vertically while Arabic is read from the right. Deen shows me another work on his laptop which too resembles Chinese script. “But it is Arabic,” he says. “This looks like Chinese. Bismillah ir Rahman ir Raheem [“In the name of God, the beneficent, the merciful”] This is Chinese tradition. You really should read from top to bottom.”

Some of the calligraphy is in both Chinese and Arabic, blended together using some very clever stylisation of the letters so the same word can be read in two languages.“The Chinese word and Arabic for Allah have same meaning. It is also... look, it is like a person doing dua [supplication] in the salaat [prayer.] This is same. Chinese word also means rasool [messenger]. In Arabic it is rasool.” The artful fusion of two of the world’s most ancient and aesthetically pleasing language scripts is what gives Deen’s work such a unique touch. No wonder he has been described by Professor Hugh Goddard, director of the Alwaleed Centre for the Study of Islam in the Contemporary World at the University of Edinburgh, as “one of the most interesting and dynamic contemporary Muslim artists.”

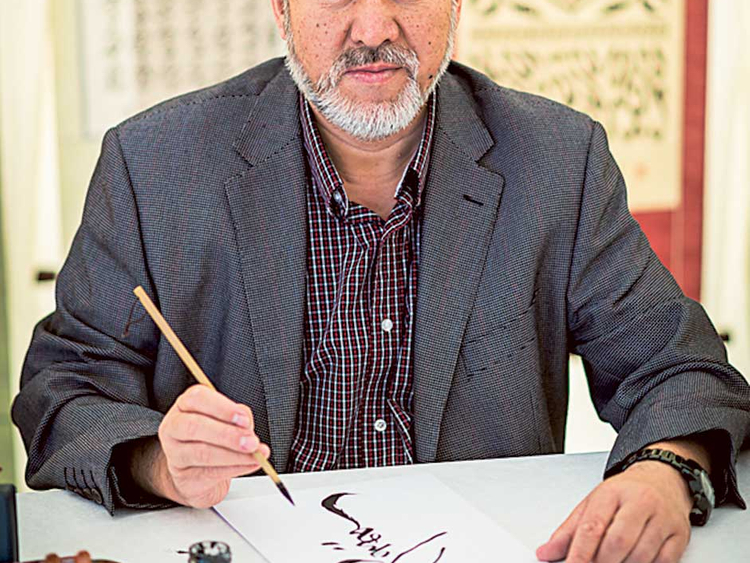

How long does it take to make one of his works? “Some work maybe one month. Some work maybe two minutes...” Deen talks about the pen he uses to draw his calligraphy. “It’s like bamboo. It is actually Chinese style qalam, pen, for writing,” he says.

My interview with Deen took place on the first floor lobby of a hotel in Lahore, Pakistan. Due to the security situation in the country there was a heavy presence of guards outside the building. Deen speaks Mandarin and Arabic — but not English. One of Deen’s students acted as an interpreter for this interview. As someone who is familiar with Quranic Arabic, however, I am struck by Deen’s great skill in fusing the Middle Eastern language with his own distinctive native Chinese.

Deen was in Pakistan for a literary event. “So beautiful. The people are lovely,” he tells me. There is a lot of interest in Islamic calligraphy in the South Asian country which has its own rich calligraphic history. However Deen’s Chinese origins make him something of a curiosity in a country like Pakistan. The ancient Silk Road connected China with the Middle East and Europe — passing through parts of what is today Pakistan. It was also an important route through which Islam spread in China.

Now centuries after those glory days, Pakistan and China have embarked on an ambitious economic corridor project, dubbed the new “Silk Road”, which is estimated to cost about $46 billion (Dh169 billion). In a country shunned by foreigners because of security concerns, there is a noticeable influx of Chinese workers in Lahore these days. It is not an uncommon sight to see photos of the Chinese premier next to his Pakistani counterpart displayed on billboards. As a result of these projects there is a lot of interest in everything related to China — including the distinct culture of its minority Muslim population.

One characteristic feature of Chinese Muslims is Arabic calligraphy. More than 3,000 students have now studied under Deen over a 15 year period. Most of them, I am told, are Muslims. How much interest is there in Arabic calligraphy in China? “There are so many Chinese people who like this [type of] calligraphy. And so many people who like this kind of writing. It has more than 1,000 years history.”

Where does Deen teach? “Masjid [mosque]. We have a very big classroom. And we teach all students free. No fees.” He also has a gallery. Deen lives in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province in China. “In our city there are more than 200,000 Muslims,” he tells me. Deen tells me about his local mosque and the popularity of Arabic calligraphy in the area where he lives. He specialises in the Sini style of Islamic calligraphy, a type of script deeply and intricately rooted in centuries of rich Chinese Muslim tradition. Deen’s Chinese name is Mi Guang Jiang. “All Chinese Muslims have Islamic names,” he says. “[On] ID card they have Chinese name.”

As I wrap up the interview, Deen suddenly speaks to me in English: “And we eat halal food!” he says, referring to our discussion on Chinese Muslims. So he does speak a bit of English. Deen only laughs at my comment.

As we get up I ask permission to take his photo. On one side there is a wall with some paintings of animals. Deen doesn’t want these representations of living beings to be in the photos — presumably out of religious reasons. So instead I ask him to stand in front of a tall plant nearby. Right behind it is a mirror fixed around a pillar. Deen’s gentle features add to his aura of gracefulness. I click the photograph, and having exchanged farewells with the visitor from China, make my way out of the heavily guarded premises of the hotel.

Syed Hamad Ali is a writer based in London.