Did ancient human Lucy fall from a tree?

Mystery that is 3.2m years old may finally be close to being solved

In 1974, the palaeoanthropologist Donald C. Johanson led an expedition to Ethiopia to look for fossils of ancient human relatives.

In an expanse of arid badlands, he spotted an arm bone. Then, in the area surrounding it, Johanson and his colleagues found hundreds of other skeletal fragments.

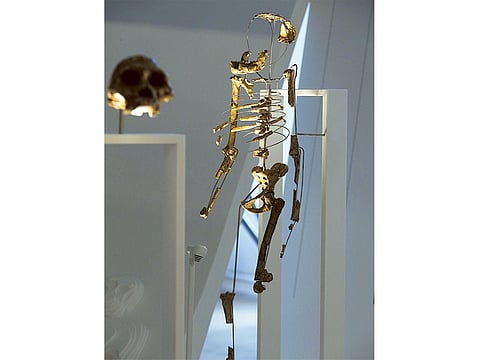

The fossils turned out to have come from a single 1-metre-tall female who lived 3.2 million years ago. The scientists named her species Australopithecus afarensis, and the skeleton was dubbed Lucy.

Four decades later, Lucy remains one of the most famous discoveries in palaeontology. Finding a single bone of that age would have been reason to celebrate; finding so much from a skeleton revealed a tremendous amount about Lucy — and about human evolution in general.

Her death, on the other hand, has been a mystery. Now, after poring over the celebrated bones, a team of scientists has concluded that Lucy died most unceremoniously: killed by a long fall out of a tree.

If they’re right, the discovery could yield an important clue to how our ancestors evolved from tree-dwelling apes into bipeds that walked the African savannah. But the new study has experts deeply divided. Some researchers are praising the research, while others, including Johanson, think the authors have failed to adequately make their case.

The new study, published Monday in the journal Nature, came about because Lucy’s skeleton — normally housed at the National Museum of Ethiopia — was taken on a tour of the United States in 2007. After a show at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, Lucy spent 10 days at the University of Texas at Austin, where scientists put her bones through a CAT scanner.

“We just decided, by golly, we were going to scan every little bit of Lucy because it may never be done again,” said John Kappelman, a palaeoanthropologist at the university.

Since then, Kappelman and his colleagues have painstakingly turned the scans into three-dimensional models, piecing together the virtual fragments to get a more accurate idea of their original shapes. Last December, he noticed a puzzling break in Lucy’s upper right arm.

A look through surgical journals suggested that the break might be a so-called compressive fracture, in which a force pushes down on a bone, sometimes even driving one bone into another.

What intrigued Kappelman was what could have caused such a compressive fracture: a fall from a great height. “It’s not something that would happen if you just tripped and fell,” he said.

Kappelman printed out a human-sized, three-dimensional model of Lucy’s shoulder and took it to Dr. Stephen Pearce, an orthopaedic surgeon at the Austin Bone and Joint Clinic. Pearce agreed that the break was a compressive fracture. Other orthopaedic surgeons consulted by Kappelman made the same diagnosis.

Kappelman and his colleagues decided to inspect all of Lucy’s bones for fractures that might have been caused by a fall. In addition to studying the virtual models, Kappelman also examined the original fossils in Ethiopia.

They found a number of breaks that looked as if they had occurred after Lucy died. But he also observed more compressive fractures, as well as so-called greenstick fractures, in which a bone only cracks on one side, much like what happens when a living tree branch breaks. Both kinds of fractures can happen during falls.

Lucy sustained many such fractures, the scientists concluded, from her ankles to her jaw. The fractures suggest that she came down feet-first and then tumbled forward, holding out her hands in a futile hope of protecting herself.

“It tells us she was conscious when she reached the ground,” Kappelman said.

If so, Lucy didn’t stay conscious for long. The fractures to her rib cage suggest crushing injuries to her internal organs that would have killed her.

Kappelman and his colleagues believe Lucy must have fallen from a tree. They base that conclusion on what geologists have determined about the environment where she lived: at the time, it was a low-lying wooded area around a stream, with no cliffs nearby.

William L. Jungers, a palaeoanthropologist at Stony Brook University who was not involved in the research, called it “a provocative but plausible scenario.”

Laura Martin-Frances, a postdoctoral researcher at the National Research Centre on Human Evolution in Burgos, Spain, also said she was impressed with the level of detail in the new study.

“For me, it’s quite accurate what they have done,” Martin-Frances said.

But other experts said Kappelman and his colleagues had not done enough to rule out other explanations for the fractures.

Ericka N. L’Abbe, a professor of anthropology at the University of Pretoria in South Africa, said that when living bones break, some parts bend. A close inspection of Lucy’s bones might have revealed traces of that bending.

“The major drawback is that they didn’t look under a microscope,” L’Abbe said.

Johanson said it was far more likely that the fractures Koppelman attributes to a fall actually came long after her death, as her skeleton was buried under sand.

“Elephant bones and hippo ribs appear to have the same kind of breakage,” Johanson said. “It’s unlikely they fell out of a tree.”

Monkeys and apes spend a lot of time in trees and have impressive adaptations for that sort of life. One of the most striking features of Lucy’s skeleton is the shape of her leg and knee bones, which look suited for walking on the ground instead.

Since the discovery of Lucy, palaeoanthropologists have found more fossils from Australopithecus afarensis. They suggest Lucy had flat feet and other traits needed for walking.