These are not fun times to be a coral reef researcher.

Like so much of environmental science, the field can be a dismal one, often devoted to documenting decline. There are mass die-offs, worldwide bleaching events, plagues of sea stars, the ominous “warm blob,” the “godzilla” El Nino and devastating oil slicks. Not to mention the ever-looming threat of climate change.

“In the coral reef world, the situation can seem dire a lot of the time,” Julia Baum, a marine biologist at the University of Victoria, told The Washington Post last year.

Which is why the discovery that some pristine reefs still exist near the uninhabited islands in the Pacific brought ecologist Jennifer Smith so much joy.

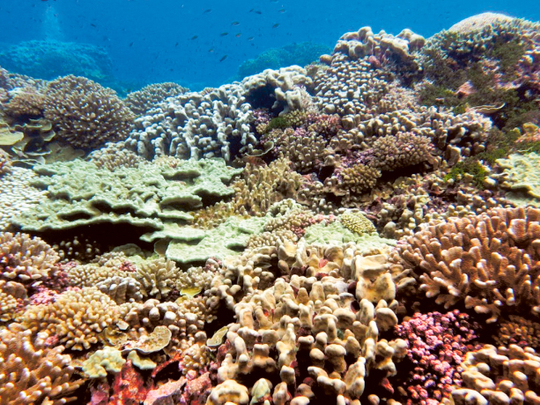

“It’s hard to fathom,” Smith, the lead author of a sweeping 10-year evaluation of central Pacific reefs, told The Washington Post. “I would jump into the water and there would be so much coral, so many different species of fish, so much complexity and colour.”

For Smith and her colleagues — their senses dulled by years of working in dying and degraded ecosystems — it was almost “a religious experience.” The scientists were very nearly moved to tears.

“I would find myself underwater, shaking my head, looking around in disbelief that these places still existed,” Smith said.

Smith’s report, which was published recently in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, examined reefs at 450 sites spanning the Pacific from Hawaii to American Samoa. The researchers wanted to determine how the reefs responded to climate change and a 1998 El Nino event that lead to widespread bleaching (a phenomenon in which stressed corals banish the symbiotic algae that give them their brilliant colours).

Some of the findings were the same, grim statistics so familiar to coral researchers. Most of the reefs around inhabited islands had been colonised by smothering macroalgae and fleshy algae — big seaweeds whose growth was likely spurred by the absence of fish (nature’s lawnmowers) and the presence of fertiliser runoff in the water. These reefs were less complex, less colourful, less developed — a monotonous suburban subdivision to a healthy reef’s thriving city.

But another discovery surprised them. If the reefs existed around uninhabited islands — away from localised problems like overfishing and pollution — they were often able to bounce back from global stressors relatively unscathed. They were covered with healthy populations of coral and coralline algae, the tiny organisms that secrete the reef’s calcium carbonate skeleton and give it its colour, and provide homes to a brilliant array plant and animal life.

“Going to these uninhabited locations, you can still find reefs that look the way they did 1,000 years ago,” Smith said.

Because the researchers had no baseline measure of the reefs’ well-being, they can’t say for sure whether the reefs near inhabited islands were always dominated by seaweed. It’s possible that the presence of macroalgae is just a natural outcome of their environment.

But if their arrival is a more recent change spurred by human interference, which seems likely, those habitats “may be losing ... one of the most significant ecological services that they are known for, their capacity to build carbonate reefs,” the authors write.

That’s because a reef is not just a reef. The calcium carbonate skeletons and the tiny creatures that constitute them provide the foundation for a habitat that is home to a quarter of all marine life, even though corals cover just 2 per cent of the ocean bottom. Their global contribution to fisheries, tourism, medicine, even shoreline protection is estimated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to be in the vicinity of $30 billion per year.

According to NOAA, a host of problems threatens to destroy some 45 per cent of reefs in the next 20 to 40 years. Many of those threats are global: Climate change makes the oceans warmer, more acidic and less hospitable to corals regardless of how far they are from the closest human.

But Smith’s findings suggest that reefs may be able to survive that menace if they are sufficiently insulated from human activity. Which, by the relatively low standards of often-grim coral research, is great news.

“It gives us incentive and motivation to believe that by managing these local impacts we can build a healthier reef ecosystem,” Smith said. “Warming events, El Nino — they’re impending. But the remote reefs show that if we can build these living organisms to be as healthy as they can be, they’re going to be much more likely to recover.”

That may be true, coral reef biologist Nancy Knowlton told the San Diego Union-Tribune, but localised efforts probably can’t insulate reefs from the effects of climate change forever. At the very best, they buy time until scientists can figure out how to address the global threat.

“The question is, how long will reefs be able to stay healthy in the context of much more frequent warming events and ocean acidification?” said Knowlton, who previously worked at Scripps and took part in the coral reef project’s initial research. “I think most reef scientists will say there are limits.”

And counterbalancing Smith’s optimism is the fact that she hasn’t visited her pristine reefs since this winter’s “godzilla” El Nino event, which NOAA said last month is prolonging a global bleaching event that was already the longest in world history.

“The corals are being hit again and again,” the agency’s Coral Reef Watch coordinator Mark Eakin said in a news release at the time.

It’s likely that even the most remote reefs in Smith’s survey are being hit too.

“Unfortunately, we don’t know whether these islands are suffering bleaching right now,” Smith acknowledged. “But given how healthy they were when we visited them our belief and hope is they will recover.”

— Washington Post