Mokha: News flash: You’ve been thinking about mocha all wrong. The espresso drink with Hershey’s syrup poured into it? That’s the coffee world’s equivalent of fake news.

To really drink mocha coffee, you’ll have to pay up”-we’re talking up to $240 (Dh881) per pound”-for the hard-to-find, chocolatey beans that hail from Mokha, Yemen.

For decades, coffee insiders have complained that Yemeni coffee had dipped in quality, wasn’t traceable, and had weird quality defects. But most also knew that a good cup of Yemeni Udaini, as the varietal is called, could convert coffee haters into third-wave believers.

Now, these high-quality Yemeni beans are being imported to the United States for the first time since the advent of speciality coffee, thanks to the social enterprise-turned-coffee roaster, Port of Mokha, named for the port in Yemen from which the first coffee shipments began coming in the 1400s. The beans are fast gaining acclaim as some of the best in the world, with industry-wide recognition that is bringing positive headlines to a war-torn nation.

The origin story

“Ninety per cent of the world’s coffee can be traced to Yemen,” said Mokhtar Alkhanshali, who founded the company after building a career in the non-profit sector. “There are a few different organisations like the World Coffee Research Organization and the Coffee Quality Institute that have done studies on coffee genetics.” He says it’s where the words “mocha” and “Arabica” both found their roots.

Alkhanshali’s upbringing sent him rotating among San Francisco, Brooklyn, and his family’s small hometown of Ibb, in central Yemen. Along the way, he got an appreciation for the Arab country’s rich farming traditions”-and the ways that American start-up culture could spur a global marketplace for rural communities.

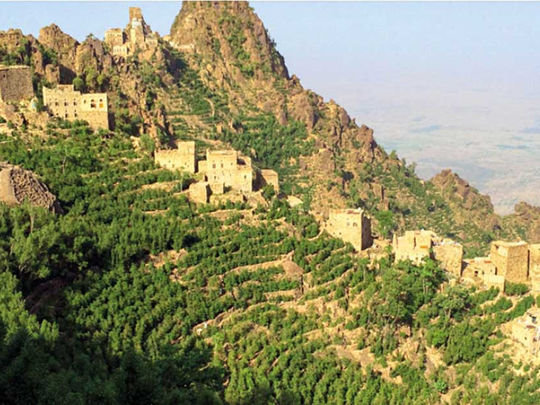

So the young entrepreneur decided to put the two together. “Coffee used to be the main trade in Haraaz,” said Alkhanshali of the 800-year-old village with hillside terraces, where he started his coffee revolution. “But now there’s a drug we have in Yemen called khat that was traditionally grown in East Africa. It’s a mild stimulant, and for every one coffee farm in Yemen now, there are seven of these khat farms.”

A burgeoning narcotics trade isn’t even the worst of the problems associated with khat farming. According to Alkhanshali’s chief finance officer, Ahmad Ebrahim, khat is a water guzzler of a plant”-using up a whopping 40 per cent of the country’s water supply. And this in a region that’s among the world’s most arid. “The capital of Yemen was supposed to run out of water entirely this year,” he said.

A coffee titan reborn

Alkhanshali didn’t know a thing about coffee when he decided to create Port of Mokha. But two years into production, his coffee dropped jaws during its first international competition, the Specialty Coffee Association’s annual meeting in 2015. The story itself is a tale of epic proportions: Alkhanshali was slated to leave Yemen for the big event with 90 kilos of beans in late March when suddenly, a violent civil war broke out.

A day before his flight, Yemen’s airports were bombed. So Alkhanshali had to reroute himself by rowboat to Djibouti in order to get to Seattle in time for judging. He made it, and after closed-door tasting sessions, coffee buyers far and wide were captivated. Blue Bottle put in an order, and before long, others came calling as well. Two years later, his East Hayma Single Farmer Lot earned the highest score ever doled out by the Coffee Review in the grading program’s 25-year history.

George Howell, the roaster who created the Frappuccino and cofounded the elite Cup of Excellence coffee grading program, said he used to source Yemeni coffee from one intrepid buyer until the 1980s, and then never saw it again. “The legend of Yemeni coffee being the most ancient, going back to the roots of coffee itself “ it was unique. And sure, when you tried it, there was nothing like it,” he told Bloomberg.

Today, Howell said he can find Yemeni coffee from a select few importers, but the ones he knows of are spotty in both quality and availability”-a problem that’s exacerbated by the ongoing war. Port of Mokha is the exception.

“You rarely get these more subtle nuances of spice and floral that are in Mokhtar’s coffees,” said Howell. “They have something I had never tasted before in a natural lot.” (By “natural,” he means beans that aren’t washed or processed before drying.) “That’s why I was willing to pay the enormous price for this coffee. It’s extraordinary. As a roaster, you just have to get it.”

Where to buy It

Howell is one of 30 roasters worldwide that will be selling Port of Mokha’s beans in the coming weeks; existing clients include Coutume CafA(c) in Paris and Tokyo, Equator Coffees in the San Francisco area, Blue Bottle in New York, and Slate Coffee in Seattle.

Since April, Port of Mokha has also been roasting its own beans and selling them online. The flagship East Hayma Single Farmer Lot brews a surprisingly clear cup full of chocolate and peach flavours”-it really does live up to the “mocha” reputation”-and sells for $42 for four ounces. By the holidays, it will also be sold as part of a $158 sampler box, with four-ounce bags from each the three regions in Yemen that Alkhanshali works in.

As for Howell, he’ll be purveying his first batch of Yemeni beans online and in his Boston-based stores next month”-for roughly $60 per quarter-pound.

Why does it cost so much? Mokhtar pays farmers 12 times the going rate per kilo of coffee ($6 instead of 50 cents) to ensure that they follow his strict picking and sorting protocols, and he provides microloans to finance equipment upgrades and other necessities. It’s a cycle of empowerment that keeps driving up the quality and quantity of Yemeni coffee, year after year and harvest after harvest. Eventually, he hopes, these incentives will convert more khat farmers to coffee growers until the drug trade is eradicated.

“Mokhtar’s success comes from a lot of teaching,” explained Howell. “He has the advantage of being Yemeni, which means he speaks the language, dresses like a local, and therefore acquires a trust and a relationship that others more educated in coffee do not attain.”

“Our first year’s production was a half a ton,” said Alkhanshali. “Six months later, it was one ton. Now, a year after that, we have 120,000 farmers and 10 tons’ worth of production.” According to Howell, the operation’s rapid-fire growth is an incredible feat. “Given the war, the fact that any coffee is coming out of Yemen at all “ it’s really a miracle.”

— Bloomberg