Amazon reimagines the bookstore format

Not just that, e-retailer wants to get its way with book bestseller lists

New York

Jeff Bezos, the chief executive of Amazon, has often struck a defiant tone when asked about the company’s dominance of the book industry.

“Amazon is not happening to book selling,” he said in a 2013 interview. “The future is happening to book selling.”

But when he made that remark four years ago, even a visionary like Bezos might not have imagined that the future would look so retro. After contributing to the demise of many bricks-and-mortar bookstores, Amazon has made a surprising pivot, with plans for a growing constellation of bookstores around the country.

Now, Amazon is bringing its experimental, data-driven approach to physical retail to midtown Manhattan, the heart of the publishing industry. Amazon has opened a store — its seventh — in the Time Warner Centre at Columbus Circle. The 4,000-square-foot space, near the site of a now-shuttered Borders store, is just a few blocks from Penguin Random House, and walking distance from Simon & Schuster and Hachette’s Midtown headquarters.

This summer, the company plans to open another store on 34th Street.

In a city that prides itself on being a literary mecca, the response to Amazon’s arrival was, unsurprisingly, mixed.

“I’m happy there’s a new store where people can see books and encounter them, but I’d rather we were in there,” said Chris Doeblin, the owner of Book Culture, an independent bookstore on the Upper West Side. “If I had the money, I would go and open a store right next to Jeff Bezos’ store.”

Amazon is planning to open six more stores this year, including outlets in Bellevue, Washington; Paramus, New Jersey; and San Jose, California.

The company’s push into physical stores might seem at odds with its origins as an online retailer. But it fits with Amazon’s continuing expansion into nearly every corner of the publishing industry. Since its founding more than 20 years ago, Amazon has become the dominant book retailer, and has created niches along the way.

It accounts for nearly half of all book sales in the US, including print and e-books, according to the Codex Group, which analyses the industry. With the introduction of the Kindle in 2007, Amazon drove the e-book and self-publishing boom.

It bought Audible, the audiobook producer and retailer, and Goodreads, the popular book review sharing site. It started a publishing company, and now has nine imprints.

The company introduced Amazon Charts, weekly best-seller lists that track not only the top-selling digital and print books on Amazon, but the ones that customers spend the most time reading. Drawing on data collected from Kindle users and Audible listeners, the most-read list compiles which books are most popular with its customers across digital formats. It is data that Amazon has long collected but never made widely public.

“This is the first time we’re sharing this information with readers,” said Susan Stockman, who oversees Amazon Charts.

With its lists, Amazon aims to redefine the notion of a best-seller, expanding it to include books that are “borrowed” from its e-book subscription service, and ones that are streamed on Audible. As a result, the lists give increased visibility to books that might not typically appear on other best-seller lists, like “The New York Times” or “The Wall Street Journal’s”.

The inaugural Amazon Charts list for most-sold fiction features five books from Amazon Publishing, out of 20 on the list.

“This is their attempt to push back and say, We’re legitimate,” said Peter Hildick-Smith, the president of the Codex Group.

All of Amazon’s acquisitions and new features are having a cumulative effect, allowing the company to draw on its vast customer base and troves of data to discover what is popular, and return that information to customers, creating a lucrative feedback loop.

Eventually, the weekly best-seller lists may be incorporated into displays in Amazon’s bookstores, and perhaps posted on Goodreads. They are already available on Alexa, Amazon’s virtual assistant, which will recite the new best-seller lists when asked.

“Amazon created a new model, and now they are hijacking the best-seller list idea to conform to what they were doing,” said Mike Shatzkin, the chief of Idea Logical Co., a book industry consulting firm. “It’s definitely an intrusion of their business model into the overall ecosystem.”

The new lists have led to speculation that they might eventually challenge more established best-seller lists like The Times’. David Naggar, Amazon’s vice-president, while not referring to a specific competing list, said, “Many of the weekly lists that are out there today tend to curate, they re-rank or add or remove books.” He described Amazon’s new lists as “unfiltered and unedited.”

Danielle Rhoades Ha, a Times spokeswoman, said that readers “value the rigour and independence of The New York Times Best-Seller Lists.”

“Unlike lists from individual retailers, our best-seller lists are based on a detailed analysis of book sales from a wide range of retailers in markets nationwide who provide us with specific and confidential context of their sales each week,” she said. “These standards are applied consistently, across the board in order to provide readers the best assessment of what books are the most broadly purchased at that time.”

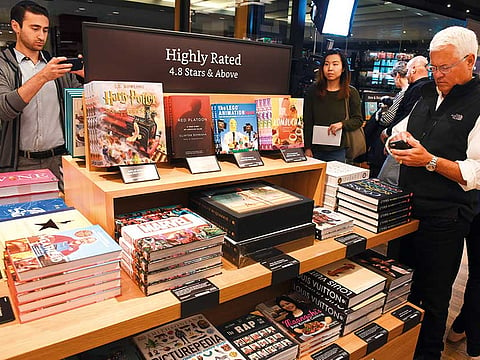

Crowdsourcing and data mining are also driving the company’s approach to its bookstores, which act as showcases for books popular with customers on the site. While the stores have traditional categories, like fiction, nonfiction and travel, the most eye-catching shelves feature categories culled from Amazon’s customer data.

“We call this a physical extension of Amazon.com,” said Jennifer Cast, vice-president of Amazon Books, during a tour of the Manhattan store. “We incorporate data about what people read, how they read it and why they read it.”

New York Times News Service