New York: There’s a $4 billion pot of cash at the Department of Justice for victims of Bernard L. Madoff’s Ponzi scheme. Thousands of them have been trying to tap the fund since it was set up three years ago, without seeing a penny. Many are elderly and live modestly; some have lost their life savings; many are losing their patience.

Daphne Brogdon, a Food Network personality in her late 40s whose family lost about $5 million in the scam, said she was ecstatic when she learned about the Justice Department fund. Now, “we’re in the dark,” she said from her home in Los Angeles, adding that she’s eager to replenish the retirement fund they lost. “It feels like we’re very disrespected. My biggest concern is not eating dog food when I’m 75.”

The more fortunate were able to file claims with Irving Picard, the trustee who is liquidating Madoff’s investment firm in bankruptcy court in Manhattan. Picard has collected $11 billion and paid $8.6 billion to about 2,500 investors since the scheme collapsed in late 2008.

Interminable wait

For those facing a seemingly interminable wait, relief is on the way from the Justice Department’s pool of about $4 billion, its administrator, Richard Breeden, said in an interview on Thursday. As many as 40,000 victims may get initial payments by the end of the year, he estimated, given the rate of claims approved so far.

“The process is more careful and takes longer than any victim might wish,” said Breeden. “The good news is that tens of thousands of victims will get paid at the end of that process who otherwise would not receive anything.”

Perhaps. But what’s taking so long?

After Breeden announced the creation of the Madoff Victim Fund, Brogdon said she and her husband, L.A. chef Mark Peel, estimated they’d soon get back as much as $200,000 — a welcome sum, she said, after the couple was forced to sell their home and take their kids out of private school.

“Obviously, a distribution of any amount would be helpful, but at least give us a timeline,” she said. “It’s been very disappointing.”

Another victim, a 50-year-old technology consultant in California, said he filed a claim in 2013 for $250,000 he lost in the fraud. Two years later, he got a letter telling him a “formal determination notice” would be sent. He’s still waiting.

Claim reviews

Breeden, 66, has hired about 50 staffers to help him review claims from tens of thousands of indirect investors — people who placed money in “feeder funds” that invested with Madoff. Picard didn’t review such claims, treating the feeder funds themselves as the investors and leaving it to them to pay back their customers. He rejected 85 per cent of claims, including almost 11,000 people who had invested with the feeders. Both men have operated within the bounds set for them, whether by the Justice Department or by bankruptcy law.

Hard job

Breeden’s been left analysing 64,000 claims from around the world. His review didn’t begin until after his appointment in December 2012 and involves many more claimants than those eligible for payments by Picard, who has a team of 200 lawyers.

“I hear they got a claim from every Tom, Dick and Harry,” said Daniel Krasner, a lawyer with Wolf Haldenstein Adler Freeman & Herz LLP in New York who represents some Madoff victims in a lawsuit against their feeder fund. “In a sense, they have my sympathy.”

Picard, 74, began work weeks after Madoff’s arrest, unravelling the fraud and piloting masses of litigation to secure funds for the victims. He’s paid out more than $5 billion after about three years.

“We work as hard as we can to complete the claims review accurately and as fast as possible,” Breeden said. “But we can’t short-circuit a careful review of the claims. I can’t just wave a wand and make payments based on guesses.”

How to get paid

To determine whether a claim is eligible, Breeden’s first, simple test is one that Picard must also follow — whether someone put in more money than he or she took out. Breeden will eventually make recommendations to the Justice Department’s Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section in Washington over which claims to pay and which to deny.

Through December 4, the Madoff Victim Fund had reviewed 51,071 claims, with 13,052 to go. Of those reviewed, 20,241, or 40 per cent, have been recommended for approval. Another 47 per cent were still under review, and 13 per cent were deemed ineligible.

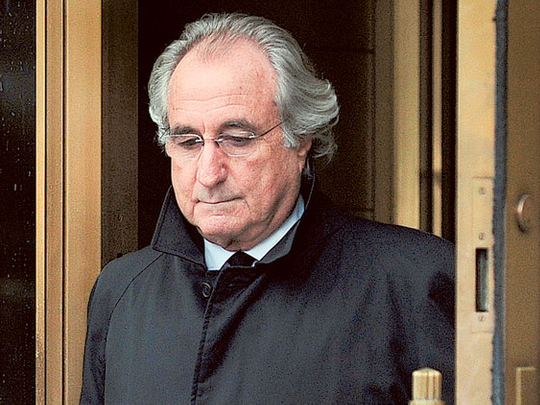

The fraud, which prosecutors said started as early as the 1960s, involved millions of pages of fake trades and account documents that were used to convince customers they owned securities in the biggest US companies. Their final account statements included about $47 billion in fake profit. Madoff, 77, pleaded guilty in 2009 and is serving a 150-year prison term in North Carolina. His case was the subject of a miniseries on ABC this week starring Richard Dreyfuss.

A $7.2b check

Days after Madoff’s arrest, Picard, a lawyer at Baker & Hostetler LLP in New York, was hired by the Securities Investor Protection Corp, an industry-financed group that seeks to make investors whole after frauds. Picard has filed more than 1,000 lawsuits against banks, feeder funds, investors and others who profited from the scam, mostly unwittingly, to help repay victims. He made the first distribution to customers in 2011, doling out $677 million.

In one suit he claimed that Jeffrey Picower, a sophisticated investor who withdrew more than $7.2 billion, should have known it was a fraud. Picower had a heart attack and was found at the bottom of his swimming pool in 2009. The following year, his widow, Barbara Picower, agreed in a settlement to hand over the whole $7.2 billion, saying she hoped it would ease the “tragic impact” the fraud had had on victims.

Picard’s fund got $5 billion, and $2.2 billion went to a fund overseen by US Attorney Preet Bharara in Manhattan, who had prosecuted Madoff. Bharara later added $1.7 billion that JP Morgan Chase & Co. paid to avoid prosecution over its role in the fraud.

Clear direction

Amanda Remus, a spokeswoman for Picard, said she couldn’t compare his work, which is based on the US bankruptcy code, the Securities Investor Protection Act and the courts, with Breeden’s. Picard’s lead lawyer, David Sheehan, said that individual, indirect investors in feeder funds still benefit from those distributions and that Picard took “extensive steps to ensure that the money received by the feeder fund is distributed to its investors.”

“You have this tension between efficiency on one hand and fairness on the other,” said Mark Powers, a lawyer with Bowditch & Dewey in Worcester, Massachusetts. “It’s possible the whole process is even more complex than the DOJ anticipated.”

Art and life

Breeden, once chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, has plenty of experience in helping victims of massive frauds get compensation. He served in similar roles following the collapses of Enron Corp., WorldCom Inc. and Adelphia Communications Inc.

He said one woman invested the bulk of her life savings with a feeder fund three weeks before Madoff’s arrest. Her claims were denied by Picard because she was an indirect investor, and the fund she invested with was denied because it made more money with Madoff than it lost.

“The answer in bankruptcy is ‘We’re sorry, you’re not eligible,’ ” Breeden said. “That’s the right answer under that law. But we can get her a recovery.”

At the end of the interview, on Thursday, Breeden said he needed to get home. He wanted to see how the Madoff story turned out.