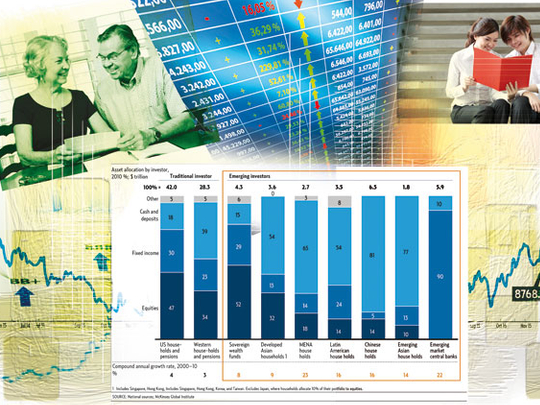

The rapid accumulation of wealth in emerging markets, where households choose to put their money in banks and government bonds, could result in the share of global financial assets in publicly listed stocks falling by a fifth in the next decade.

This will make it difficult for many investors to meet their saving and financial goals. A new study by management consultant McKinsey, noted that emerging market households choose lower allocations of equities — less than 15 per cent — in their portfolios.

In comparison, there is a 42 per cent allocation to equities in the United States and 29 per cent in the European Union (as of 2010). However, several factors, including: aging investors moving out of equities to bonds and cash, the growth of alternative assets such as hedge funds and private equity, new financial regulations and a decade of poor equity market returns and high volatility; have also reduced the appetite for equities in developed economies.

Assuming that these trends in developing and mature economies are not going to change significantly, McKinsey expects a decline in the share of global financial assets held in equities from 28 per cent to 22 per cent by 2020. But, the report points out: "We have seen that ordinary investors in countries with strong equity investing habits consistently earn higher returns on their savings."

It cites the example of US, where in the past 15 years when household equity allocations have averaged nearly 50 per cent, total annual returns on all financial assets have averaged almost 5 per cent. During that period in Germany, where households placed 20 to 25 per cent of their financial wealth in equities, annual returns averaged 1.5 per cent. This helps explain why household financial assets are growing faster in the United States than in Germany despite USA personal savings rate in US less than half of Germany.

While a case is being made for investors to increase their exposure to equities, to generate a return above inflation, the reality is many are not comfortable with the level of risk that comes with this.

In India, for example, there has been a steady shift towards a diversified range of investment options, including equities and insurance, as income has increased over the years. Half of India's population are under the age of 50, but as Nitin Jain, principal fund manager of Kotak Mahindra (UK), points out: "This young India is also insecure. Social security and insurance coverage (both life and health) in India are lacking and the needs of this young population are different from those of their counterparts in the more developed economies." Could one blame them for being more conservative in their approach to investing?

Large sections

The mainland Chinese mentality, with large sections of the population raised from poverty and is now a part of middle class now, is no different.

"We have witnessed a strong burst of savings into low risk vehicles in China over the last few decades," Mark Livingston, investment director, emerging market equities, Fidelity Investments, points out. "This stands to reason as much of the population was barely at subsistence levels before growth accelerated, so the tendency to preserve capital at such an early stage should be considered a rational decision."

But, he advises that attitudes to investing in equities in India, China and Russia, among others, should change if stock prices appreciate in value for an extended period of time. "However, such investments will likely be biased towards the sophisticated large purchaser of securities, while the small scale investor will probably be left behind."

The McKinsey report recommends that all investors need to look beyond their home markets, especially those from mature economies where there holdings are skewed toward their home markets.

"To meet investing goals, households and institutions will need to look to where GDP grows most rapidly, which means focusing on the most promising companies based in developing countries and multinational companies that have successful operations in those markets," it advises. However to go after stocks in such markets is fraught with challenges. One, as the report notes is to find sources of return commensurate with the risk—and to find good values.

Challenges

"Today, with the limited amount of publicly floated shares in emerging markets, valuations can be high. [But] for retail investors, one relatively low risk way of gaining exposure to emerging market growth will be through investing in multinationals that have a strong emerging market presence," Susan Lund, director of research, McKinsey Global Institute and one of the co-authors of the report, told Gulf News.

And, as Catherine Yeung, the Hong Kong-based investment director of Fidelity Investments, argues in times of heightened volatility and risk aversion, emerging markets offer little protection from the fears surrounding growth in developed markets.

"One fundamental explanation for the highly correlated recent performance is that Asia, excluding Japan, is still significantly driven by exports to the developed world and any reassessment of developed world growth has an impact on the region," she says. "An equally persuasive explanation is that, for brief periods, the markets are simply not driven by an assessment of the differing fundamentals of the respective areas but instead by emotion," Yeung says. "When fear levels surge among investors, they tend to act indiscriminately by selling all risk assets to seek safe havens such as gold and the highest-quality government bonds."

Long-term growth

"This ‘risk on-risk off' nature of investor behaviour," Yeung adds, "which has been pronounced in the last several years, means that emerging and especially Asia, excluding Japan, have not decoupled in the very short-term."

Due to the globalisation of capital markets, cross-regional equity correlation has risen steadily over the past 10 - 15 years and that's a challenge too. "More recent high levels [of correlation] have diminished the benefits of cross-regional diversification and macro volatility has been a more significant driver of sector and stock correlation," says Dan Dowding, senior executive officer at Killik and Co. "Whilst yes this has impacted sentiment, equity investors need to seek out areas and sectors of long term growth. They should not merely invest in emerging markets as a place to diversify their portfolios, but because they believe these regions will grow more rapidly than others."

The McKinsey study finally suggests that rather than thinking about equities and fixed-income investments as two completely different asset classes, it may be more useful to "buy both the equity and the debt of companies with the best performance potential." In this regard, bank equities, with their changing characteristics and continuing growth as a share of overall market capitalisation of major exchanges, justify a special approach for investing in them.

Promoting stock investments

To cultivate the emerging investor classes of Asia and other regions, the McKinsey report points out the asset managers will be required to tailor products to fit their preferences and budgets.

The industry needs to develop simple mutual fund products that deliver returns that are higher than traditional products, while encouraging investors to limit stock market risk through portfolio diversification and dollar cost averaging, says Mark Livingston, investment director, emerging markets equities, Fidelity Investments.

"A culture of consistent investment in equities over time needs to be encouraged as to ‘smooth' out the effect of bouts of volatility," he says. "The ease of investment and keeping minimum thresholds within a degree of affordability are of vital importance. And finally, consideration should be made to the needs of the female, who in many developing countries, is increasingly responsible for the investment decisions of the household."

The Systematic Investment Plan (SIP) is an example of a reasonably successful platform in India that has channelled small savings into equities, says Nitin Jain, principal fund manager, Kotak Mahindra (UK). "Indian investors love fixed yielding bank deposits and mutual funds have found a tax efficient alternative in the form of fixed maturity plans. Going forward, we will continuously see innovation by insurance companies and asset management companies to attract the new emerging class of investors."

In mature economies, poor stock market returns and ageing households may work against professional asset management. But, the report points out that: "Individual investors in the United States and other advanced economies have done a poor job accumulating retirement savings in their own accounts and in their employer-sponsored investment programs. Some solutions, such as increasing the personal saving rate, will require policy changes. But asset managers can take steps to increase saving."

Investors must be educated about the financial implications of them living longer, says the McKinsey report. "In this vein, some asset managers may need to redesign target-date mutual funds if they reduce or eliminate equities too early to meet the ongoing accumulation needs of clients today."

Why investors do not like equities

Even if demand for company shares increases until 2020, there will be an "equity gap" between the money invested and what companies will need to fund growth, the Mckinsey report points out. While there is evidence that cultural norms, perceptions, and attitudes do play an important role in households' decisions to invest in equities, there are also structural reasons why equity investing differs across countries, Susan Lund, director of research, McKinsey Global Institute told Gulf News.

In Japan, for example, real returns on equities have actually been quite poor over the last two decades. Thus Japanese household's low equity allocation (now less than 10 per cent) is a rational response to the prospects for returns. In fact bond returns have far exceeded equities there.

Moreover, in many parts of the world, the typical household income is not high enough to make any amount of risk to wealth acceptable to individuals, Lund points out.

Policymakers in emerging markets could also do more to improve the ‘soft' factors that make equity investments attractive, says Lund. "This includes improving corporate transparency and accounting standards, as well as better protection of minority shareholders."

While agreeing that properly functioning equity markets are crucial to ensure increased participation, Tom Stevenson, investment director at Fidelity Investments, is not convinced that preference for bank deposits in emerging markets will last.

"As countries get richer, their citizens increase their propensity to invest in equity markets because they can afford to take higher risks and they seek the higher returns that only stock markets have historically provided," he writes in the Expert Opinions section of the company's website.

Also, Stevenson feels the case for developed economy investors moving out of equities into cash and bonds is overstated. To protect against the "ravages of inflation," he notes, they will continue to keep a higher allocation to shares than has been the conventional wisdom in recent years. The so-called "lost-decade of poor market returns since 2000 and the recent market falls could be close to running its course, he adds. And with investors' memories being short, once equities start rising again, it is likely that they will look at equity markets as "a natural home for long term savings again," Stevenson says.