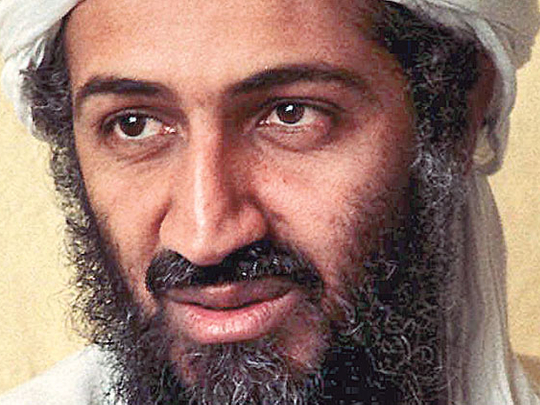

I started writing this business column with Osama Bin Laden on my mind. While many will feel the need to acknowledge his death, I wondered how I should do so. I can only compare the effort it took Arabs to build in Dubai and destroy in New York.

The death of Bin Laden closes the chapter on an era when fundamentalism was seen as an existential threat that justified the continued state of martial law in many Arab states. Sure Hezbollah and Hamas still exist but between an ambitious new-Egypt and a weakened old-Syria, their effectiveness will certainly not be what it was, so far.

Looking at the level of political and social upheaval in the Arab world today, many would argue that Osama was a horrible manifestation of the general discontent in the Arab world. The Arab Spring uprisings are a healthier manifestation of that same discontent.

Related articles:

In pictures: The life of Osama Bin Laden

Global reaction following Bin Laden's death

Al Qaida lost its relevancy years ago

Osama Bin Laden: Most wanted face of terrorism

In focus: Osama Bin Laden

But why did one succeed while the other failed? Why did ‘Death to America' not resonate? I suppose, in the end, nobody wants to live in Tora Bora — not even Bin Laden apparently — but, rather Dubai.

People rose because they wanted to live well. It must have been hard for Egyptians and Tunisians to understand how a city-state like Dubai, and the UAE in general, could develop with none of the resources of their countries, let alone their political and social institutions. It was no longer about being like London or Paris but rather like Dubai.

One of the most memorable scenes that captured the depth of frustration that drove the Arab spring was a few seconds of a YouTube video on the Egyptian revolution. In it a young man says: "Leave all this talk about democracy and freedom. What I really want is when an Egyptian has a good idea he can realise it in here in Egypt and does not have to travel abroad."

For me, this captured the fundamental spirit of not only that revolution, but also the contemporary human condition. People, with a global outlook and cognisant of their self-worth, want a shot at life. They want to make something of themselves.

Think of all the Arabs that left their countries and were able to flourish and grow elsewhere. Perhaps now they are optimistic that their children can return home and succeed.

But their optimism will be tempered by cynicism. The Diaspora proved that the grass is in fact greener on the other side. It will take a lot to convince them to come back.

But what about those who never left? An Arab renaissance may not be upon us but pity those who will oppose it. They will not be able to hide from the fury of those who are demanding a new beginning.

Challenge

The challenge now, not only for governments but nations as a whole, is to become productive, competitive, entrepreneurial and creative. The political and security smokescreens are fading. There is no longer a need for military leadership, but rather a socio-economic one. And, there is little time and much work to be done.

Egypt may re-emerge as a beacon of entrepreneurial might and cultural light. But the Gulf may see oil, its main source of income, lose markets to coal and green energy, among others.

Some have noted recently that this 21st century resembles 12th much more than it does the 20th: a time when no singular power ruled the world unchallenged. In this time, the Arab world must learn to fend for itself. If it does not show up for the competition, the rest of the world won't lament our absence.

They will simply take note and capitalise on it. There are no more political excuses for economic deficiency and there are certainly many answers to how broad prosperity can be pursued and achieved without the oppression of the masses.

Mishaal Al Gergawi is an Emirati current affairs commentator.