Governments should not take onus of job creation

Responsibility should rest with private sector even in a time of extreme stress

How big can a government be? Or in other words, how much should the state contribute to the economy, or GDP, via government spending?

Now don’t take what I say as a criticism to Maynard Keynes’s theories, not at all. As a matter of fact, I am an advocate of his theories. And what made me think of this was mainly a series of events, extending over the past five years or so.

No one is interested in short run growth or limited spikes in employment. If a government is to be actively involved in employment, its contribution should be minimal and extremely efficient. That is, the government, any government to be frank, should be stricter in its selection and recruitment processes than publicly-owned companies.

This is for a very simple reason, in that there is no way any government in the world can create enough jobs, even in a sluggish or no-growth environment. Neither can it sustain an increase in employment through recessions.

The concept of austerity is bitter any way you put it. And people’s psychology has been shaped to negatively take in any sort of news that includes the concept. No one can blame them.

Throughout Europe, the norm has been to fire people from the public sector every time austerity is mentioned, and additional lay-offs were scheduled if the initial phase didn’t work as the European Central Bank, or worse, the IMF had hoped. It’s a vicious cycle how employment is dealt with during recessions: people default on payments and more defaults increase the risk for companies.

When companies default and are to announce bankruptcy, what should governments do? If you are in the “too big to fail” list, you would receive loans, or grants, or you could be nationalised. Jobs would be initially saved, but what will happen when a new recession knocks at the door and the government payroll is blown out of its normal proportion?

As for the remaining companies, they start cutting down costs to try to survive or at least make financial statements look appealing enough for crisis survivors to acquire them. Additional layoffs might be on the new owner’s agenda anyway.

When governments act tough, austerity measures are applied. Payroll lists are reviewed and people are laid off the next day. In Greece, over 2,000 employees had their services ended as part of Greece’s obligation to cut off 15,000 state jobs by 2015. Unemployment among the Greeks has reached 27 per cent, with unemployment among the youth at a peak of 62 per cent.

Because these numbers are in one way or another similar throughout Europe, what kind of message do they communicate? If the public sector had no more on its payroll than were needed to carry out the functions at ministries and institutions, would countries face such high unemployment levels?

And this is not it. The only way out after excessive government recruitment is either by people being patient and tolerant until the government starts hiring again, or until the private sector gets into investment mood again. One last resort would be for government-owned entities to be privatised. This comes through foreign direct investments which countries in distress are trying to attract.

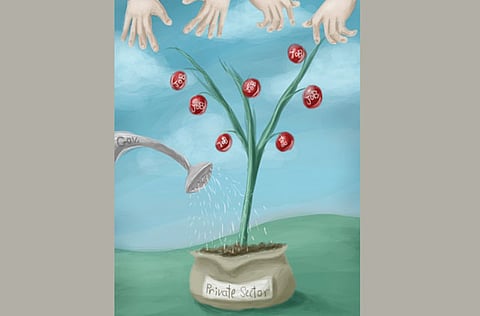

A government should not go out of its way to create jobs; neither should it be the main job creator in any economy. The private sector needs to grow with governments involved only in guarding its national interests, as well as ensuring the recruitment of its national citizens. Reasonable percentages should be required in different industries, with no pressures exerted on hiring the non-qualified.

The money saved from public current accounts should be spent on training people to compete normally for available jobs. Accordingly, a government’s role should be more of promoting an investment-friendly atmosphere by introducing laws that encourage local investments and others that attract foreign ones. These would normally include protection of investments and avoidance of double taxation.

Finally, a government’s direct intervention in the jobs market should be limited to creating employment spikes that would make up for shortfalls when various reasons might slow down the creation of jobs by the private sector. Now the last thought that I want to leave you with is this: how can governments maintain employment levels created by its public projects once these are completed? (Hint: consider the effect on public capital and current accounts).

— The writer is a commercial consultant and a commentator on economic affairs. You can follow him on Twitter at www.twitter.com/aj_alshaali.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox