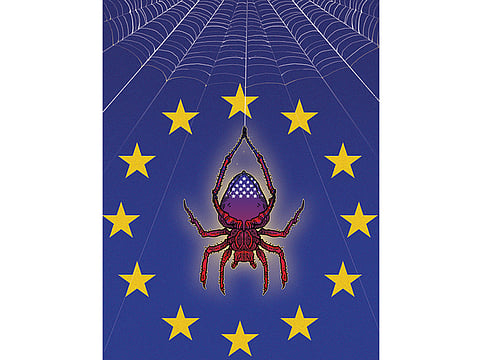

Europe gets draconian with its data privacy

Policy will only undermine Continent’s web-based entrepreneurship and benefit US tech giants

When it comes to crafting good digital policy, Europe has failed its first big test.

In May, the European Commission announced that it would create a unified digital market of 500 million consumers that would add €415 billion (Dh1.6 trillion, $463 billion) to the European Union’s GDP and create some 3.8 million jobs.

Unfortunately, a recent decision on one key digital issue — data privacy — threatens to derail that effort.

In June, the EU’s home and justice ministers voted to retain significant national powers over the protection of digital privacy, rather than creating a single set of rules that would apply in all 28 EU countries. If the European Parliament approves their proposal, divergent national rules would be reintroduced.

Even more worryingly, this would open the door for provisions outlawing the benign, low-risk data mining that drives online advertising.

Online advertising allows EU citizens to access information, educational material, commerce channels, and entertainment sites without paying for them directly, and the amount being spent on it in Europe is growing fast.

The industry’s revenues have more than quadrupled since 2006, even as the overall European economy has stagnated.

Business model

The EU’s privacy crackdown threatens to undermine all of this. Not only will it create an administrative burden through additional costs and bureaucratic hassles, it also raises the real possibility that the new rules will undermine the business model of many of Europe’s most prominent online companies.

That would be a pity — one that could have been easily avoided. In 2012, the European Commission presented a proposal to replace the EU’s existing data protection legislation, the latest version of which had been drafted in 1995, when the internet played only a tiny role in the economy.

The initial text was promising. It aimed to harmonise Europe’s fragmented legal framework, provide businesses with a helpful “one-stop shop”, and reassure consumers that their data were being used properly.

Unfortunately, many of the most benevolent provisions have since been discarded. At the June ministerial meeting, the important one-stop-shop principle was gutted.

Instead of allowing businesses to deal with the data protection authority in the country where they are headquartered or have their main European base, member-states are insisting that national regulators maintain control.

Under the newly proposed rules, any “concerned” authority could object to a decision by another national regulator, triggering a complex arbitration procedure involving all 28 agencies.

Strict data rules

The ministers also adopted a broad definition of personal data. Both cookies (small pieces of data stored on a web surfer’s computer) and IP addresses (a code used to identify a computer when it is connected to the internet) would be included — even though neither provides a link to a particular individual.

At best, this broad, indiscriminate definition of personal data threatens to create unnecessary obstacles for EU-based digital advertisers. At worst, it will outlaw their business model.

Unnecessarily strict data rules will hurt European companies disproportionately. Google, Facebook, and other American internet giants are in a position to receive explicit consent from users.

But Europe’s online sector is dominated by business-to-business companies with little-known brands that process consumer data but lack direct contact with users. As a result, the only real alternative for European internet companies will be to work with large American platforms and become even more dependent on them.

The UK, Sweden, Norway, and the Netherlands are global online leaders, but many other European countries are lagging far behind. As a result, the digital economy contributes about 4 per cent to the EU’s GDP, compared to 5 per cent in the US and 7.3 per cent in South Korea.

International competitors

These new regulations will ensure that European companies will be left trailing far behind their international competitors.

Europe is facing an important choice. To be sure, the EU needs to reassure its citizens that their data will be used properly; measures that do this will help the digital economy grow.

But the continent’s policymakers must remember that a digital single market cannot exist as long as there are rules that reinforce divergent national approaches to privacy and hinder the internet’s use of anonymous data for digital advertising.

At stake is an entire generation of European digital entrepreneurs.