Expect income and wealth inequality to be a prominent theme for the candidates who declare an interest in running for US president in 2016, whether they are Republicans or Democrats.

The issue is important on its own merits, but also because of its connections to economics, politics, demographics, race, gender and geopolitical extremism. It will resonate throughout the campaign, and beyond, and will inevitably be vulnerable to catchy yet misleading political rhetoric.

Here are nine things to remember as the presidential race heats up:

1. Global inequality (that is, across countries) has declined thanks to the development spurt of emerging economies such as China and India. Within individual countries, however, it has worsened in a remarkably consistent fashion in both the advanced and developing worlds.

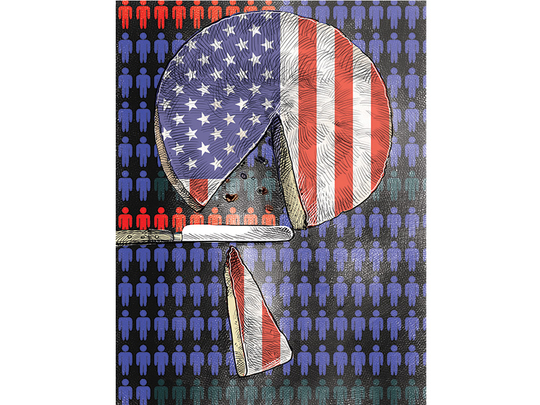

A very large portion of the income generated in the last few years has accrued to the highest earners (in the US, for example, the top 1 per cent has captured 95 per cent of the income gains since the 2008 global financial crisis). And the richest of the rich have increased their share of national wealth. (In the US, the top 0.1 per cent owns a remarkable 22 per cent of the wealth, three times as much as 40 years ago, and almost as much as the 25 per cent belonging to 95 per cent of the population.)

2. This pronounced worsening of inequality in both wealth and income is caused by an unusual combination of drivers — structural, secular and cyclical. On the production side, the displacement impacts of globalisation and technological innovations have tended to hit hardest among the lower-middle and lower class segments of the population.

The same is true of the disappointing growth and job recovery in many Western economies, whether you consider this weakness to be cyclical or part of a secular stagnation. Meanwhile, the most influential — and perhaps only — cyclical policy response, that of central banks, aims to promote growth through higher prices for financial assets (which have made the rich even richer).

3. The normal redistribution mechanisms are functioning inadequately, if at all. This is particularly the case for active fiscal policy, which has been rendered largely inoperative by real or perceived worries about debt. This tool has been further paralysed in countries such as the US by what Mark Blyth of Brown University calls a “can’t, won’t, shouldn’t” Congress.

4. The longer this type of inequality persists, the greater the risk that it will erode future opportunities for already challenged segments of society. This is especially true of access to education and health care, two important components of a remunerative employment career.

5. Inequality’s effects have moved far beyond questions of fairness and morality. The worsening imbalance is now fuelling political extremism and accentuating gender and race divides. It is also undermining economic recovery by holding back demand (the rich spend a lower portion of their income) and harming productivity and supply potential.

6. The problem is of increasing interest to society, including the rich. Case in point: A 700-plus page tome by a relatively unknown French economist (‘Capital in the Twenty- First Century’, by Thomas Piketty) surged to the top of the New York Times Best Seller list last year and has been a topic of discussion for a growing number of billionaires and millionaires.

7. There are solutions, starting with macro and sectoral improvements. A spurt in growth would help greatly, as would greater emphasis on infrastructure programmes, which enhance both productivity and employment (and possibly wages, too) and can be financed at very low interest rates.

8. There also is a long list of micro measures, offering not just a menu for politicians from both parties but also areas where bipartisan agreement could be achieved in a more functional political system.

If most of these measures were implemented — and this is a huge if — they would constitute a critical mass that would not only counter a further worsening in inequality but also materially improve the situation.

There would still be a trade-off at the margins between equity and efficiency, though without undermining growth in any consequential way. Going from the least controversial to the most contentious, this list includes: progress in equalising wages between genders; closing tax loopholes that tend to favour the rich; increasing the taxation of carried interest; making mortgage relief more progressive; raising the minimum wage; increasing the inheritance tax, and raising top marginal tax rates.

To be effective, such measures would need to be combined with pro-growth reform of the corporate tax system and the targeted allocation of incremental revenues to efficient spending on social sectors, such as education and health.

9. Despite a rather large menu of possible macro, sectoral and micro measures, the likelihood of policy action in the short run is quite low, if not minimal. But that doesn’t mean there is no scope for improvement.

There are steps that individuals and companies can, and should, take. Enhancing education materially improves employment prospects (compare the 8.6 per cent jobless rate for those without a high school diploma to the 2.5 per cent rate for those with college degrees).

Companies can use technology and behavioural finance to promote productivity-enhancing access to cost-effective financial services for the more vulnerable segments of society. And they can certainly do more in the areas of worker training and apprenticeships.

As we assess how well our politicians reflect these nine issues in their campaign promises, there is one central fact to keep in mind: The “inequality trifecta” (income, wealth and opportunity) has worsened so much that it is in the interest of the vast majority of Americans to support corrective actions.

— Washington Post