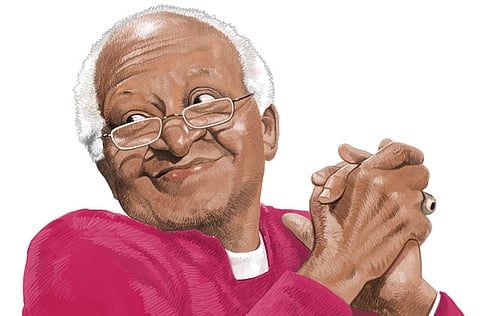

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: ‘The moment I wanted to be a priest’

Priest as loved as Mandela has been able to unite most hostile governments

Dubai: A life can change with the smallest gesture. A kind word, a kind deed, a second thought, a first impression. Most of us are never aware of that moment of transformation, the minutia of a minute that matters most. But Archbishop Desmond Tutu remembers clearly that paradigm shift, where the meaning of life became as clear as the purest water, the bluest sky, the truest truth.

In was Sophiatown, Johannesburg, as the teenaged Tutu walked with his mother. She was a cleaner and cook at a school for the blind, all with the wrong colour skin in a nation determined to carve its being on the inequalities and racist laws of apartheid – white was right.

“A white man in priest’s clothes walked way and tipped his hat to my mother,” Tutu later recounted. “I couldn’t believe my eyes – a white man who greeted a black working-class woman in school.”

For Tutu, the seminal moment confirmed his desire to enter the Anglican seminary, becoming a priest to make the word a better place, carry out the message of Christianity that whatever you do to those who matter least matters most.

Earlier this month, the retired Archbishop of Cape Town was awarded the prestigious Templeton Prize. It’s just the latest of a long string of accolades that this soft-spoken man of the cloth has garnered in a long life of fighting injustice, poverty, racism, prejudices, governments, dictators, detractors and anyone who stands in the way of an unshakeable belief that all are created equal and all are to be be loved as equal.

Each day, in his office above a printing shop in a forgettable suburb of Cape Town, he begins by quietly petitioning the Almighty on behalf of those who have emailed, written and telephoned him for help. And for plenty of others who haven’t.

During what he calls “the dark old days” of apartheid, when travel bans, threats to his life and the killing of close friends were constant challenges to his faith, he never stopped praying daily for each cabinet minister of the white regime - by name.

The Archbishop’s decision to retire from the public stage following his 79th birthday nearly four years ago has provided him with more time for prayer and reflection, he hopes; the democratic South Africa he helped to create is as much in need of his urgent petitions as ever.

He believes that its future is bright. “If I ever had doubts before about the possibilities of this country, they are now gone,” he says. “Truly. We are nothing less than a scintillating success story. That is our destiny.”

In recent years he has directed the fearless moral challenges he once aimed at his apartheid rulers to the African National Congress, which has governed since 1994. Its leadership may now feel relief at his promise “to shut up, keep quiet, say nothing” once he bows out.

“The Arch”, as he is happy to be known, is vexed by what he sees as the enrichment of his country’s well-connected political minority, as well as its appalling crime rate and Aids pandemic - and has made no secret of his views.

His small office is cluttered with cartoons, life-affirming signs such as “We Don’t Believe in Miracles - We RELY on them!” and trophies bestowing the free world’s greatest honours for a lifetime of public service.

“The price of freedom is eternal vigilance,” the Archbishop says in his sing-song voice, setting down his cup which bears the legend “Growing old is inevitable, growing up is optional!”.

“At one time people were squirming in their seat about our handling of the Aids crisis and stories about curing it by eating beetroot, and now they are giving standing ovations for our response. So that is very good turn of events,” he smiles.

The news of his reduction in workload, allowing him to “grow old gracefully” with Leah, his wife of 58 years, was met with resignation and sadness across South Africa.

At the World Cup, the sight of the diminutive priest, enveloped by his national team’s football strip, hat and scarf as he gave the most rousing speech of the tournament, confirmed his place in the world’s affections, which is matched only by that for Nelson Mandela.

But calls on his time have mushroomed in recent years, the more so as an increasingly frail Mandela has faded from the limelight.

In the decades of his steadfast campaigning against apartheid, he presided at the mass funerals of slain activists, and intervened with baying township crowds to stop them “necklacing” their enemies – putting petrol-soaked tyres around the necks of victims and setting fire to them. Throughout it all, he preached peace and forgiveness - setting him on a path to chairmanship of the historic Truth and Reconciliation commission which helped the new South Africa come to terms with its past.

The sight of him breaking down in tears during months of harrowing evidence was beamed around the world.

Only the Archbishop could have ever coined the phrase “the Rainbow Nation”. His gift for uniting enemies and calming fears led to his intervention in some of the world’s most intractable situations.

Robert Mugabe and the Israeli government are just two who have borne the colourful brunt of his conscience.

Robert Mugabe once labelled him “that evil little Bishop” after being cautioned to give up power lest he find himself at The Hague war crimes tribunal. But, in the end, hasn’t the Zimbabwean despot seen the Archbishop off?

“Yes he has!” he replies. “But things will be OK in Zimbabwe. Great good comes out of suffering, even evil suffering.

“Take Nelson Mandela: so many people say ‘What a waste, imagine what he might have achieved if he had been freed earlier’. But he would never have been the person he is today without all of those 27 years in jail.

“He went to jail as an angry young man who believed that the very best white person was a dead white person.

“Those years were crucial in the making of the man who emerged. Suffering is an inescapable ingredient for people with magnanimity.”

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox