Hong Kong is running out of space for its dead

It can be a four-year wait for a plot to intern the ashes of a dead relative

HONG KONG: Happy Valley seems like a perfect name for a place to rest in eternal peace. One of the oldest Christian cemeteries in Hong Kong, it’s located on a hillside not too far from the central business district, it overlooks the racecourse with which it shares its name, and the oldest graves here go back to 1845, four years after the British arrived to claim the territory in a treaty and turn into a pulsing trading post and gateway to China. Yes, it’s not a stretch to say that this area is the dead centre of Hong Kong, with final resting places nearby, too, in cemeteries for the departed Muslims, Hindus, Jews, Parsis and others who wove together the rich fabric of the island and its port.

The older the graves, the lower down they are, located near the flatlands and final homestretch of the racecourse, while those dating from the 1930s and 1940s are closer to the top. Either way, there’s simply no room for any more — the cemetery has reached its dead end.

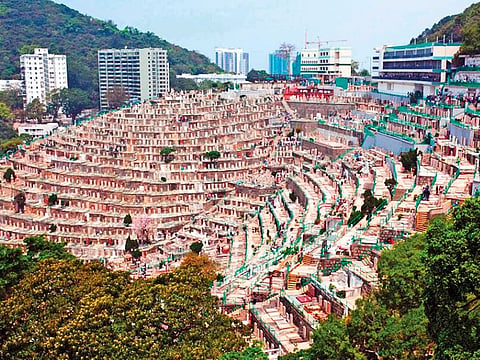

Right now, across Hong Kong, there’s a severe scarcity of places to bury the dead — so much so that local government officials estimate that there are 200,000 human remains waiting for a place to rest in peace. Even if a final plot is found for a relative’s ashes, there’s no guarantee that those there will rest in peace forever — and burial plots for the dead turn out to be even more expensive than finding a place to live in a city that has the most expensive real estate in the world. A plot large enough to permanently contain a relative’s ashes can set families back as much as HK$1.8 million (Dh842,000) — enough to buy an apartment in the UAE.

Highly priced plots

It’s a problem that’s not just unique to Hong Kong.

In Singapore, an eight-lane highway is planned, covering the 100,000 graves of some of the earliest settlers seeking eternal rest in the island-state’s Bukit Brown cemetery.

The choice for families in Hong Kong is to buy one of the highly priced plots in private columbaria, or wait for four years for a plot in a public columbarium to become available.

Right now, there are about 7.4 million living on the island and the population is ageing — meaning that the number of people waiting for burial is expected to double to 400,000 in just four years’ time.

Kenneth Leung Ka-keung, of Hong Kong-based burial company Leung Chun Woon Kee, said it’s an issue that’s not being addressed. “The government doesn’t have a plan after 2022,” he told the South China Morning Post. “We are very concerned about the future shortage and imbalance of urn spaces. At an average wait time of four years it takes longer for people to wait for niches than a public housing flat.”

Green funerals

For families, it’s important that the remains of lost loved ones be buried close to where they lived — and close to living family. The belief is that the dead watch over the living, and the living pay their respect to those deceased to gain favour and good fortune. There’s also a reluctance too in Chinese culture to cremate remains and lay ashes to rest in urns in columbaria, scattering them in gardens of remembrance, or in burials at sea. Yet it’s these options that are being pushed by government officials in promoting “green funerals” in an effort to end the burial crisis.

Whether for scattering cremated ashes of the deceased in gardens of remembrance or at sea, green burial can conserve the environment.Food and Environmental Hygiene Department

Some 90 per cent of those who died in Hong Kong last year were cremated, and the former British-run colony began promoting cremation as a long-term option in the mid-1960s. A resting space in a public columbarium can cost HK$4,000 — but only after that current four-year wait.

Gulf News visited Hong Kong just as the annual Ching Ming grave-sweeping festival wrapped up — a time when relatives visit the graves of their ancestors, make offerings, pray and literally sweep the graves of those gone before. It’s a festival of honouring the dead that has roots in Chinese history going back for more than 2,500 years.

As it stands now, Asia’s ageing population is projected to hit 923 million by mid-century, according to the Asian Development Bank, putting the region on track to become the oldest in the world.

Conflicting traditions

Since 2007, authorities have also been promoting green burials by scattering ashes at sea or in 11 gardens of remembrance. But such practices conflict with Chinese traditions that hold that burying remains in an auspicious spot on a mountainside or near the sea are vital for a family’s fortunes.

The government has been trying to change attitudes with educational videos and seminars at retirement homes. It’s even set up an electronic memorial website where families can post photos and videos of the deceased and send electronic offerings of plums or roast meat. Interest remains limited, with green burials rising from a few dozen in 2005 to more than 12,000 last year.

With more than 46,000 dying each year on Hong Kong island, the government’s Food and Environmental Hygiene Department, responsible for promoting green burials, is eager to get more residents to sign up to their programmes.

“The government spares no efforts to promote green burials,” a spokesman for FEHD said as it launched a green burial register — an initiative to promote the practice and get the living to sign up for when they’re gone. “Whether for scattering cremated ashes of the deceased in gardens of remembrance or at sea, green burial can conserve the environment and help save land resources.”

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox