After Snowden fled US, asylum seekers in Hong Kong took him in

About two weeks later he turned up in Moscow

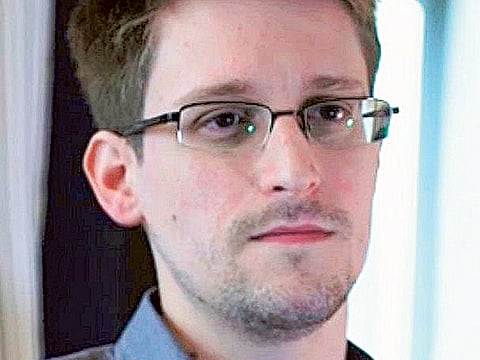

Hong Kong: When the 42-year-old Filipino woman opened the door of her tiny Hong Kong apartment three years ago, two lawyers stood outside with a man she had never seen before. They explained that he needed a place to hide, and they introduced him as Edward Snowden.

“The first time I see him, I don’t know who he is,” the woman, Vanessa Mae Bondalian Rodel, recalled in an interview. “I don’t have any idea.”

Rodel is one of at least four residents of Hong Kong who took in Snowden, the former National Security Agency contractor, when he fled the United States in June 2013. Only now have they decided to speak about the experience, revealing a new chapter in the odyssey that riveted the world after Snowden disclosed that the NSA had been monitoring the calls, emails and web activity of millions of Americans and others.

At the time, governments and news outlets were scrambling to find the source of the leaks, which were published in The Guardian and The Washington Post.

In an interview recorded in a hotel room, Snowden identified himself and revealed he was in Hong Kong. Then he went into hiding. About two weeks later he turned up in Moscow.

It was never clear where Snowden was holed up during those critical days after leaving his room at the five-star Mira Hotel, when the United States was demanding his return. As it turns out, he was staying with Rodel and others like her — men and women seeking political asylum in Hong Kong who live in cramped, substandard apartment blocks in some of the city’s poorest districts.

They were all clients of one of Snowden’s Hong Kong lawyers, Robert Tibbo, who arranged for him to stay with them.

Rodel said Snowden slept in her bedroom while she and her 1-year-old daughter moved into their apartment’s only other room. Not knowing what he would eat, she bought him an Egg McMuffin and an iced tea from McDonald’s.

“My first impression of his face was that he was scared, very worried,” she recalled.

Rodel said her unexpected guest “was using his computer all day, all night.” She said that she did not have internet service but that Tibbo provided him with mobile access.

On Snowden’s second day there, he asked Rodel whether she could buy him a copy of The South China Morning Post, the city’s main English-language newspaper, she said. When she picked up the paper, she saw his picture on the front page.

“Oh my God, unbelievable,” she recalled saying to herself. “The most wanted man in the world is in my house.”

Jonathan Man, another of Snowden’s lawyers in Hong Kong, said that he had initially considered hiding him in a warehouse but that he and Tibbo quickly dismissed the idea. Instead, after taking him to the United Nations office that handles refugee claims in Hong Kong and filing an application, they brought him to the apartment of a client seeking asylum.

“It was clear that if Mr. Snowden was placed with a refugee family, this was the last place the government and the majority of Hong Kong society would expect him to be,” Tibbo said. “Nobody would look for him there. Even if they caught a glimpse of him, it was highly unlikely that they would recognise him.”

There are about 11,000 registered asylum seekers living in Hong Kong, mostly from South and Southeast Asia. They generally cannot work legally and survive on monthly stipends that rarely cover living costs.

Tibbo said he turned to these clients for help in part because he expected them to understand Snowden’s plight. “These were people who went through the same process when they were fleeing other countries,” he said. “They had to rely on other people for refuge, safety, comfort and support.”

He noted that Snowden was not wanted by the Hong Kong police at the time and that he had advised his clients to cooperate with the police if they showed up. He said his clients had decided come forward in the hope that the publicity would put pressure on the Hong Kong authorities to expedite their applications for refugee status and resettlement.

Rodel, for example, has been waiting nearly six years for a final decision on her application, which she declined to describe.

After a few days with Rodel and her daughter, Snowden spent a night with Ajith Pushpakumara, 44, who said he fled to Hong Kong after being chained to a wall and tortured for deserting the army in his native Sri Lanka.

Pushpakumara said he had listened to online radio broadcasts about Snowden and was surprised to suddenly find him in the dingy apartment that he shared with several men. He realised Snowden was in the same situation he was, hiding in a small room. “I was worried about him,” he said.

Supun Thilina Kellapatha, his wife and their toddler also sheltered Snowden, putting him up for about three days in their 250-square-foot apartment.

Kellapatha, 32, who said he sought protection in Hong Kong after being tortured in Sri Lanka, described their guest as a tired man who was unfailingly polite.

“He said, ‘You are a good man,’” when he arrived at the apartment, Kellapatha recalled. “But I feel he is better than me, because he respected me.”

Kellapatha and his wife, Nadeeka Dilrukshi Nonis, said they were not worried about hosting Snowden. “I don’t think I take the risk,” he said. “He is the one who take the big risk.”

When Snowden left, he left the couple $200 under a pillow, which they said they used to buy necessities for their daughter. “Sometimes I tell Supun, maybe he forgot us,” Nonis said. “I want to tell him, ‘Edward, how are you? We will never forget you.’”

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox