Massive cyber attack shocks world

Audacious global blackmail attempt underscores the vulnerabilities of the digital age

San Francisco/Washington: Hackers exploiting malicious software stolen from the National Security Agency executed damaging cyberattacks Friday that hit dozens of countries worldwide, forcing Britain’s public health system to send patients away, freezing computers at Russia’s Interior Ministry and wreaking havoc on tens of thousands of computers elsewhere.

The attacks amounted to an audacious global blackmail attempt spread by the internet and underscored the vulnerabilities of the digital age.

Transmitted via email, the malicious software locked British hospitals out of their computer systems and demanded ransom before users could be let back in — with a threat that data would be destroyed if the demands were not met.

By late Friday the attacks had spread to more than 74 countries, according to security firms tracking the spread. Kaspersky Lab, a Russian cybersecurity firm, said Russia was the worst-hit, followed by Ukraine, India and Taiwan. Reports of attacks also came from Latin America and Africa.

The attacks appeared to be the largest ransomware assault on record, but the scope of the damage was hard to measure. It was not clear if victims were paying the ransom, which began at about $300 (Dh1,101) to unlock individual computers, or even if those who did pay would regain access to their data.

Security experts described the attacks as the digital equivalent of a perfect storm. They began with a simple phishing email, similar to the one Russian hackers used in the attacks on the Democratic National Committee and other targets last year.

They then quickly spread through victims’ systems using a hacking method that the NSA is believed to have developed as part of its arsenal of cyberweapons. And finally they encrypted the computer systems of the victims, locking them out of critical data, including patient records in Britain.

The connection to the NSA was particularly chilling. Starting last summer, a group calling itself the ‘Shadow Brokers’ began to post software tools that came from the United States government’s stockpile of hacking weapons.

The attacks on Friday appeared to be the first time a cyberweapon developed by the NSA, funded by US taxpayers and stolen by an adversary had been unleashed by cybercriminals against patients, hospitals, businesses, governments and ordinary citizens.

Targets

The attacks Friday are likely to raise significant questions about whether the growing number of countries developing and stockpiling cyberweapons can avoid having those same tools purloined and turned against their own citizens.

They also showed how easily a cyberweapon can wreak havoc, even without shutting off a country’s power grid or its cell phone network.

In Britain, hospitals were locked out of their systems, and doctors could not call up patient files. Emergency rooms were forced to divert people seeking urgent care.

In Russia, the country’s powerful Interior Ministry, after denying reports that its computers had been targeted, confirmed in a statement that “around 1,000 computers were infected,” which it described as less than 1 per cent of its total. The ministry, which oversees Russia’s police forces, said technicians had contained the attack.

Some intelligence officials were dubious about that announcement because they suspect Russian involvement in the theft of the NSA tools.

But James Lewis, a cybersecurity expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, said he suspected that criminals operating from Eastern Europe acting on their own were responsible. “This doesn’t look like state activity, given the targets that were hit,” he said.

Those targets included corporate computer systems in many other countries — including FedEx in the United States, one of the world’s leading international shippers, as well as Spain’s Telefonica and Russia’s MegaFon telecom giant.

It could take months to find who was behind the attacks — a mystery that may go unsolved. But they alarmed cybersecurity experts everywhere, reflecting the enormous vulnerabilities to internet invasions faced by disjointed networks of computer systems.

There is no automatic way to “patch” their weaknesses around the world.

“When people ask what keeps you up at night, it’s this,” said Chris Camacho, the chief strategy officer at Flashpoint, a New York security firm tracking the attacks. Camacho said he was particularly disturbed at how the attacks spread like wildfire through corporate, hospital and government networks.

Another security expert, Rohyt Belani, the chief executive of PhishMe, an email security company, said the wormlike capability of the malware was a significant shift from previous ransom attacks. “This is almost like the atom bomb of ransomware,” Belani said, warning that the attack “may be a sign of things to come.”

Weapon of choice

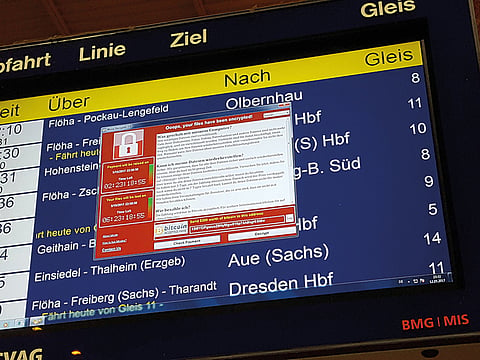

The hackers’ weapon of choice Friday was Wanna Decryptor, a new variant of the WannaCry ransomware, which encrypts victims’ data, locks them out of their systems and demands ransoms.

Hours after the Shadow Brokers released the tool last month, Microsoft assured users that it had already included a patch for the underlying vulnerability in a software update in March.

But Microsoft, which regularly credits researchers who discover holes in its products, curiously would not say who had tipped the company off to the issue. Many suspected that the US government itself had told Microsoft, after the NSA realised that its hacking method exploiting the vulnerability had been stolen.

Privacy activists said if that were the case, the government would be to blame for the fact that so many companies were left vulnerable to Friday’s attacks. It takes time for companies to roll out systemwide patches, and by notifying Microsoft of the hole only after the NSA’s hacking tool was stolen, activists say the government would have left many hospitals, businesses and governments susceptible.

“It would be deeply troubling if the NSA knew about this vulnerability but failed to disclose it to Microsoft until after it was stolen,” Patrick Toomey, a lawyer at the American Civil Liberties Union, said Friday. “These attacks underscore the fact that vulnerabilities will be exploited not just by our security agencies, but by hackers and criminals around the world.”

On Friday, hackers took advantage of the fact that vulnerable targets — particularly hospitals — had yet to patch their systems, either because they had ignored advisories from Microsoft or because they were using outdated software that Microsoft no longer supports or updates.

The malware was circulated by email. Targets were sent an encrypted, compressed file that, once loaded, allowed the ransomware to infiltrate its targets. The fact that the files were encrypted ensured that the ransomware would not be detected by security systems until employees opened them, inadvertently allowing the ransomware to replicate across their employers’ networks.

Employees at Britain’s National Health Service had been warned about the ransomware threat earlier Friday. But it was too late. As the disruptions rippled through at least 36 hospitals, doctors’ offices and ambulance companies across Britain, the health service declared the attack a “major incident,” warning that local health services could be overwhelmed.

Britain’s health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, was briefed by cybersecurity experts, while Prime Minister Theresa May’s office said on television that “we’re not aware of any evidence that patient data has been compromised.”

As the day wore on, dozens of companies across Europe, Asia and the United States discovered that they had been hit with the ransomware when they saw criminals’ messages on their computer screens demanding $300 to unlock their data. But the criminals designed their ransomware to increase the ransom amount on a set schedule and threatened to erase the hostage data after a predetermined cut-off time, raising the urgency of the attack and increasing the likelihood that victims would pay.