Uncharted canvases: Aya Tarek on art, innovation and the future of design

Aya Tarek on how art can shape the future of creative industries

During IBDS 2025, The Kurator spoke with Aya Tarek about her practice, her vision for innovation, and the role of art in shaping the future.

The Innovation by Design Summit (IBDS) returned to Doha in 2025 with Msheireb Properties, gathering global leaders in business, design, and technology to explore how design drives innovation, sustainability, and cultural impact.

“We believe that design is more than just artistic pursuit; it is a driver of innovation, sustainability, and cultural dialogue”, says Dana Kazic, Director of Doha Design District. “That is why we are proud to work with Msheireb Properties to spark meaningful conversations about the future of design.”

Among the voices joining that dialogue is Aya Tarek, Alexandria-born artist and 2024 UNESCO Sharjah Award laureate. Known for fearless experimentation across murals, film, and digital media, Tarek has exhibited internationally from São Paulo to New York, blending classical training with emerging tools like virtual reality to push the boundaries of contemporary art.

THE KURATOR First of all, congratulations on receiving the 20th UNESCO Sharjah Prize for Arab culture. What did that moment mean for you and how do you see it in the context of your journey as an artist?

AYA TAREK That moment was both personal and historic. I became the youngest Arab artist to receive the prize, which marked a milestone in my career. From painting public walls in Alexandria to projects in Geneva and exhibitions in Milan, it felt like recognition that my experimental approach, moving between street, digital, and institutional spaces, had carved out its own relevance.

T.K. In your view, what role does street art or public art more broadly play in shaping cultural narratives today?

A.T. Street art creates visibility in the most direct way, on walls and streets where daily life unfolds. For Arab culture, that visibility is vital, especially when so many narratives are shaped elsewhere. Public art speaks in the language of the people; it provokes, confronts, and tells stories that don’t always find space in mainstream media. It keeps culture alive, authentic, and rooted in its voices.

T.K. You’ve often worked outside the gallery system, on streets, walls, in digital spaces. How do you feel about being recognised by such an established cultural institution?

A.T. It feels like part of a natural curve in art history. Think of the Mexican muralists, once revolutionary, later commissioned by major cities and museums. Or graffiti, once criminalised, now filling institutions like Tate Modern. My practice began on Alexandria’s streets with that same spirit of experimentation. To see museums and cities now commissioning public works shows how what begins outside official outlets can redefine culture. For me, this recognition affirms that public and experimental art isn’t peripheral. It is central to how culture moves forward.

T.K. Your work often turns public space into a dialogue. How do you decide which urban surfaces deserve your attention?

A.T. Scale is important. I choose walls that are bold and visible, but also rooted in the life of a neighbourhood. I care about how a mural speaks to the architecture and rhythm of a street, and sometimes I deliberately break that rhythm to create contrast. What excites me is when a wall becomes more than a surface, when it turns into a place where people pause, talk, and reclaim difficult spaces as part of shared memory.

T.K. You’ve said that you’re “more concerned with technique and style than politics”, yet your work often feels politically charged. How do you navigate that line?

A.T. I may not have used the right wording before. My approach is visual. I don’t try to push a single, direct message. I respect my audience too much to make the work that simplistic. What drives me is creating art that is both intellectual and approachable, pieces that can hold their own in terms of craft and technique. That’s where I differ from many street artists. I’m not interested in reducing ideas, but in opening space where visual language invites people to engage and interpret.

T.K. You were an early graffiti artist in Egypt, essentially pioneering a movement. How has the scene evolved since your early days with the group Fo2 we Ta7t?

A.T. In 2008, as a teenager at the Faculty of Fine Arts, I turned my grandfather’s attic into a studio with friends. That became the base for Fo2 we Ta7t, the first collective in Egypt to experiment with street art. We were restless, breaking free from the academy, testing what art could become outside classrooms. Those early nights painting walls felt raw and uncertain, but they laid the foundation for what followed. Today, the scene has shifted. Street art in Egypt has become more commercial, murals in malls, projects tied to gentrification, companies turning it into a business model. I’ve stayed in my lane, keeping the original objective intact: to make work that is bold, experimental, and accessible in public space. At the same time, I adapt, because change is part of urban art, without losing the spirit we started with back in that attic.

T.K. Street art in the Arab world has a complicated relationship with visibility, censorship, and expression. How do you navigate that terrain?

A.T. Visibility and censorship have always been part of the equation. Anything on a wall might be erased the next day. But that ephemerality is part of the language of street art. It teaches you to work with risk, to accept change, and to keep creating. I focus on what I can control. Whether a mural lasts a week or a year, what matters is that it sparks dialogue. Public art will always carry tension between expression and restriction, but I see that tension as fuel. It forces me to keep the work alive and evolving.

T.K. Your work feels rooted in Alexandria, but in dialogue with cities around the world. How do you balance the local and the global?

A.T. I see visual art as a universal human language. Growing up in 1990s Alexandria shaped that view. The city I knew was a mix of nationalities, cultures, and religions. My home was right next to the Library of Alexandria, and I spent summers meeting people from all walks of life. That gave me a sense that local stories are always connected to something bigger. When I travel, I study and honour the host city’s culture without slipping into appropriation. I play with the balance between familiarity and disruption. A mural might echo something rooted in a neighbourhood’s history but also introduce elements that surprise, so the work belongs to its place yet speaks universally.

T.K. There’s a distinct humour and surrealism in your work, especially in your use of characters. What draws you to that?

A.T. My work has always circled around humanity in search of divinity, our longing for beauty, our embrace of imperfection, and the attempt to find meaning while creating it. That theme evolves with each stage of my life. The lens I carry is both surreal and humorous. It’s how I make sense of the world, and that sensibility shapes my art. For me, art is not a fixed answer but a moving dialogue, between the sacred and the absurd, the intimate and the universal.

T.K. You’ve worked across animation, NFTs, murals, and more. What excites you most about emerging technologies today?

A.T. I feel privileged to have witnessed so many technologies unfold in my lifetime. Growing up in the 1990s, I practiced with drawing, painting, and printmaking before computer graphics evolved into something new. I was curious, learning these tools as they advanced, and they became part of my artistic language.

Now, with the AI revolution, I’m even more excited. These tools help me imagine and produce ideas on a scale our predecessors couldn’t have dreamed of. For me, technology isn’t a replacement for creativity. It is an expansion, pushing expression into realms once impossible.

T.K. How do you view your role as a cultural bridge, not just as an Egyptian artist, but also as an Arab voice in global discourse?

A.T. I’m aware of how the global art world often frames Arab artists as if we’re inventing ourselves for the first time. That comes from a long history of erasure. Our experiences and lineages were never properly documented, so every generation is treated as unprecedented. I resist that orientalist narrative. My role isn’t to reinvent the wheel, but to continue it, to insist that our stories and aesthetics have always existed and evolved authentically. What I can do is add my voice to that continuum, making work that is experimental and of its time, but rooted in a deeper history that deserves recognition.

T.K. Looking ahead, what do you wish people understood about your work, and what excites you about the future?

A.T. My practice has evolved in ways I couldn’t have predicted, and I hope audiences allow space for that evolution rather than defining me by the past. What excites me now are ambitious public commissions, cross disciplinary collaborations, and the challenge of stepping into new environments that push me out of comfort and into reinvention.

CAPTIONS

01 Aya Tarek

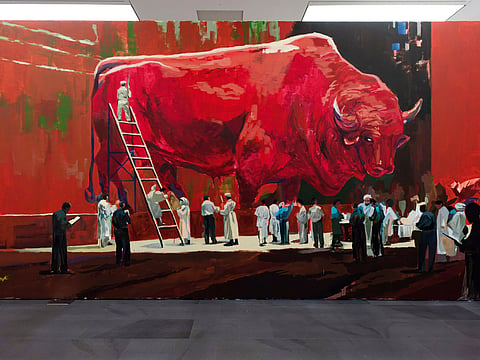

02 Mudec Invasion by Aya Tarek in Milano (2025)

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox