Winning the fight for global education

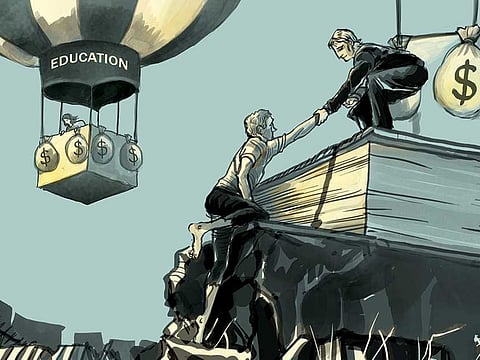

The world secured funding that helped combat diseases. Today, the same needs to be done for education

In 2000, when the world adopted the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), a promise was made: Education is a right and every child must be educated. Last week’s Oslo Summit on Education for Development confirmed the growing consensus within the global education community about what must be done to honour that pledge.

Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg and Foreign Minister Borge Brende are to be congratulated. They not only helped to turbocharge the discussion, but also — and more important — helped to forge policymakers’ resolve to find the resources that will be required to get the job done under the upcoming Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, which will succeed the MDGs).

Indeed, the first achievement of the Oslo summit was a call to get much more serious about closing the $39 billion (Dh143.44 billion) annual gap in external funding needed to ensure that every child attends pre-primary, primary and secondary school. This is the bedrock of the proposed SDG to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote life-long learning opportunities for all”.

At the meeting’s close, Norway announced the establishment of a Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunities. The new commission, convened by Norway, Indonesia, Chile and Malawi, and headed by former British prime minister Gordon Brown, will make the case for investment in education and reversal of the decline in overall funding. I believe this gives education the same opportunity that the health sector had following the adoption of the MDGs.

At that time, the world secured the donor funding and introduced the innovating finance mechanisms that enabled widespread vaccine distribution and led to better ways to combat HIV, malaria, and other diseases. Today, we need to unlock the same doors to ensure that governments, philanthropists, the private sector, and others step up to meet the world’s education needs.

The Oslo meeting also advanced work that is already underway to establish a cohesive response to the education crisis afflicting tens of millions of children caught up in war, civil strife, epidemics, and natural disasters. Children across Africa, the Middle East and Asia have been driven out of school — many for years — compounding their misery and jeopardising their futures. The aim under the emerging approach is to have a new programme that responds to these children’s needs ready to start next year.

The Oslo meeting also affirmed new horizons. No one spoke more eloquently than Malala Yousufzai, the Pakistani schoolgirl and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Her appeal for 12 years of quality primary and secondary education for all children electrified the meeting’s participants. “If nine years of education is not enough for your children, then it is not enough for the rest of the world’s children,” she declared. “The world needs to think bigger and it needs to dream bigger.”

And so we shall. As world leaders headed to Addis Ababa earlier this week for the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, which ended yesterday, they were guided not only by what happened in Oslo, but also by other important recent markers of global sentiment. For example, education has been endorsed repeatedly as the highest development priority in United Nations My World Surveys. Likewise, in May, the Incheon Declaration of the World Education Forum endorsed quality education for all and called for the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) to be scaled up and strengthened.

The draft outcome document for the conference in Addis reflected the rapidly emerging consensus: “We will scale up investments and international cooperation to allow all children to complete free, equitable, inclusive, and quality early childhood, primary and secondary education, including through scaling up and strengthening initiatives, such as the Global Partnership for Education.”

So what needs to be done in the future — to take this agenda forward?

For starters, it is essential that advocacy efforts to ensure better resourcing of the current GPE model continue, accompanied by a strategy to attract new donor governments and new private-sector and philanthropic engagement. Moreover, there is a critical need to design innovative financing solutions that will work at scale, as well as to ensure better donor coordination, while efforts within developing countries to create functioning taxation systems and transparent government accounting must be better coordinated with efforts to improve domestic resource mobilisation.

Last but not the least, it is essential to identify and agree on the best approach to meeting the educational needs of children in crisis and conflict.

As with the MDGs’ success in achieving its health targets, ensuring the capacity to meet the world’s educational needs will require exploring seed financing and then upscaling, after appropriate due diligence, new ways of working. Much can be done to create global goods platforms for educational inputs like books, technology, professional support materials for teachers, and student learning assessment mechanisms. By bringing to bear the efficiencies that come with scale, such an approach promises to support country-led education planning and implementation.

The GPE’s members — 60 developing-country partners, donor countries, civil-society organisations, teachers associations, private-sector actors, and others, including UN agencies — are all ready to realise the SDG vision. Those most committed to these goals know that this is the time, this is our fight, this is what we must do for our children throughout the world.

— Project Syndicate, 2015

Julia Gillard is also chair of the Global Partnership for Education.