Why climate change is a partisan issue in America

Climate is an issue where the two parties cannot even agree what it is they are actually discussing and such huge gaps are impossible to bridge

When President Donald Trump announced last week that the United States would pull out of the Paris climate accord, the reaction around the world was almost universally negative. Analysis of the decision focused on the political influence of the oil, gas and coal industries and, particularly, those industries’ close ties some of Trump’s top aides.

Yet many of these analyses failed to address a related question: Why is this another of those areas (like health care and guns) in which America is unique? Other countries with politically powerful and economically significant oil, gas and coal industries accept both the reality of climate change and the need to do something about it. Other countries have climate sceptics, but only in America do they dictate the agenda of the ruling political party. Only in America is the very existence of climate change considered a partisan issue.

It is worth remembering that this was not always the case. As recently as 2008 the Republican Party’s presidential nominee, Senator John McCain, was a leading voice on climate change. During that year’s campaign he was arguably more animated about the issue than Barack Obama.

That same year Newt Gingrich, the former House Speaker who has been one of the American right’s most outspoken ideologues for more than 30 years, made a TV ad in which he and the then-current speaker, Nancy Pelosi, sat together on a sofa in front of the US Capitol and issued a remarkable joint appeal.

“We don’t always see eye-to-eye, do we Newt?” Pelosi says.

“No, but we do agree, our country must take action to address climate change,” Gingrich replies. Adding: “If enough of us demand action from our leaders, we can spark the innovation we need.”

Three years later Gingrich — who was getting ready to run for president at the time — appeared on Fox News to call the ad “the dumbest single thing I’ve done in recent years.” In that same appearance he also said: “I actually don’t know whether global warming is occurring.”

It is common to trace the changes of heart by Gingrich, McCain and others to the brutal partisanship of the Obama years, but the fact is that Republican attitudes on the issue had been shifting for a long time before Obama took office.

McCain may have been a bold voice on climate change a decade ago but it’s worth remembering that he stood out precisely because even then, he was largely out of step with his party on the issue.

This mindset goes further back. When Al Gore was the Democratic presidential nominee in 2000, the GOP singled out his environmentalism as evidence of woolly-headedness. Today it remains the thing most likely to draw sneering dismissals of him among Republicans. Two decades earlier, part of Ronald Reagan’s success lay in rejecting the calls for national sacrifice and austerity that had characterised the presidencies of Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford. Reagan’s message was that America is a land of bounty and that anyone who tells you it needs preserving both lacks faith in the country and prioritises austerity over jobs and growth. This has resonated with multiple generations of American voters.

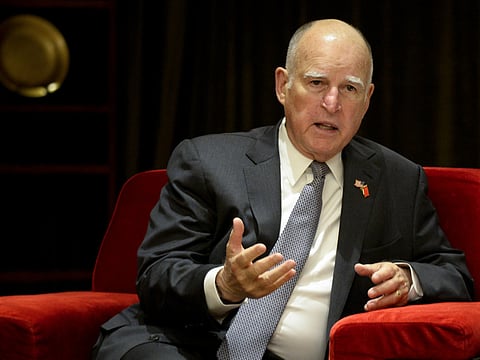

So the partisanship around climate change — the tendency to see it as an either/or tradeoff pitting jobs against preservation — did not spring into being a few years ago. It has been growing, and slowly hardening into the US political mindset for generations. The case of California Governor Jerry Brown is particularly instructive. Brown is the most successful (some might argue the only) major American politician to have built his career around environmentalism (even Gore, despite a long and solid environmental record, only made climate change central to his political persona after leaving office).

In recent weeks Brown has emerged as the most forceful and articulate spokesman for the Paris Accord in US politics, organising state and city-level officials to do what they can to mitigate the effects of Trump’s decision. Yet this is the same Jerry Brown who was also governor of California more than 40 years ago, in the 1970s, and whose attempts to move onto the national stage — three unsuccessful presidential campaigns and a failed senate race — all stalled in no small part because his concern for the environment made him seem kooky and economically unrealistic to an entire generation of voters. Most Republicans still see him that way.

Brown’s profile is rising precisely because Democrats nationally are embracing his views in a way that they did not 30 or 40 years ago. That very fact only further alienates him from Republicans.

I wish I could say there was any sign all this is going to change — that America will evolve toward the rest of the world on at least this one question. But the reaction at home to Trump’s announcement shows how thin a hope that is.

Like so many other things in US politics today, climate is an issue where the two parties cannot even agree what it is they are actually discussing. Gaps that wide are close to impossible to bridge.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches political science at the University of Vermont.