What ‘Countering Violent Extremism’ programmes hide

Diminishing essential social institutions at the expense of domestic society

Over the past few years, multiple governments, non-profit organisations and study centres have been building up Countering Violent Extremism, or CVE, as a set of programmes aimed at reducing radicalisation. These efforts seek to stem the tide of citizens who either travel to war zones like Syria and Somalia to fight alongside non-state militant groups, or who conduct violent attacks domestically.

Each subsequent, horrific, high-profile attack on western soil, from Paris to San Bernardino and Brussels, appears to affirm the necessity of this sort of work. These were perpetrated not by foreign individuals but by Muslims from the cities and towns where they carried out these gratuitous acts of violence.

As well-founded as these steps seem, the essential formula of CVE means that national security functions expand into vital social institutions, at significant risk to their essential missions.

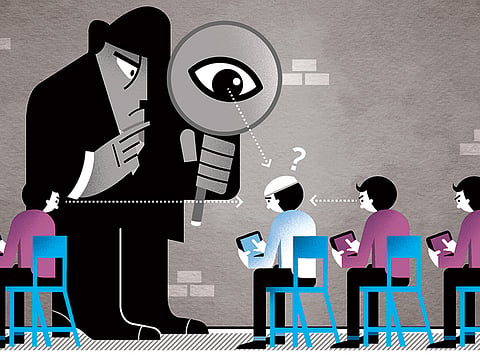

Some governments are turning schools into sites of surveillance. In the UK, teachers are now statutorily bound to identify students who show signs of radicalisation. The country also requires prison officials, mental health workers and others to do the same. This is based on the notion that these individuals are on the state’s frontlines in relation to the Muslim community. They are not trained, yet they referred more than 4,000 people — the youngest of whom was four years old — for further radicalisation detection last year alone.

The warning signs they are looking for; being withdrawn and quiet, prone to occasional outbursts and holding rebellious views, sound alarmingly similar to normal teenage emotions. They can also conflate too easily with having radical political views and being prone to carrying out violence.

Among teachers, programmes such as this are highly unpopular. They divert from the fundamentally crucial purpose of the schools as institutions, to educate and encourage socialising among students.

There are unintended consequences. If teachers are told to detect potential future terrorists, how does that impact their relations and interactions? Suspicion by teachers and fear of being referred by students skews this foundational interaction. Targeting young Muslims as potential suspects is very likely to produce alienation and forced silence, which themselves have been held up as symptoms of radicalisation.

Similarly, programmes that enlist members of the community, religious clerics and mental health professionals — such as the FBI’s test Shared Responsibility Committees — diminish autonomy and their crucial roles in society.

Local police serve a crucial role in maintaining public order and providing for the public’s safety. To the extent they are enlisted to engage communities through the lens of counter-radicalisation, this can lead very easily to stereotyping and extra scrutiny on those who may hold unpopular opinions.

There is a larger concern that CVE-style measures harm the public sphere. Through CVE, governments are, after all, engaging in propaganda, the deployment of one-sided information and expression for instrumental purposes — to spin or selectively represent issues towards pre-determined agendas.

While most CVE programmes are careful to say they target all forms of extremism, in practice they emphasise Muslim communities and signal that the population as a whole must be regarded with suspicion and extra-close scrutiny.

Similarly, addressing groups of citizens through such a lens results in a chilling effect. Muslims learn to keep quiet about politics. They will avoid voicing unpopular political views that could lead to them being held up as extremists. This in effect denies them access to the same freedoms of speech enjoyed by other citizens and worsens a sense of discrimination and inequality.

The denial of voice and agency could actually increase the allure of joining militant groups that promise empowerment, action and belonging to a greater cause. It seems then that CVE could just as easily spiral into one more instance of war on terror measures actually exacerbating the problem they claim to address.

Most important, CVE has become a distraction from the more important conversations western societies should be having about transnational violence and their responsibilities for the spread of terrorism in the past fifteen years.

Focusing on the radicalisation of young Muslims obfuscates the extremist violence of western foreign policy, nowhere seen more clearly than in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as in Yemen and Libya.

The linkage to foreign policy is direct. The US and its allies backed the predecessors of Al Qaida in Afghanistan during the Cold War. They also created the conditions for the rise of Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) by illegally invading Iraq in 2003. These cases demonstrate the old notion of blowback in foreign adventurism by states chasing immediate objectives at the expense of long-term repercussions.

Many of the militant groups sponsoring attacks have justified them as retribution for western foreign policies.

Yet, foreign policy is only present in CVE to the extent that it fits within the vague checklists that mark out individual pathologies to be flagged up. Specifically, the presence of foreign policy is simply as a means of marking those individuals as potential threats who criticise it.

CVE is pursued in lieu of officials and members of the public having to deliberate critically about structural causes — which then has the effect of maintaining root causes in perpetuity.

Officials too easily hide behind the primordial excuse that this would be giving in to the terrorists or somehow legitimises their grotesque violence. That is just a deflection from what is really needed, a critical re-evaluation of western governments’ own recent legacies of violent extremism.

Instead of western foreign policy establishments and national security apparatuses being taken to task for the failures and great human costs of their military interventions, invasions, regime changes and dubious alliances overseas, they prefer to pursue this latest buzzword, a paradigm that diminishes essential social institutions at the expense of domestic society.

— Will Youmans is an Assistant Professor at George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs.