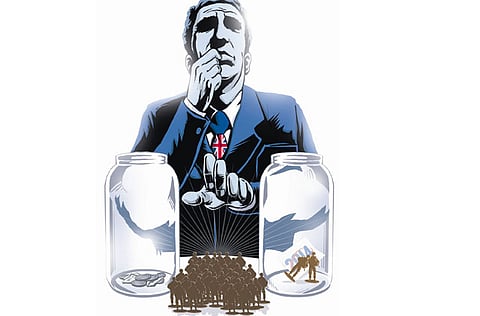

Tough choices for Britain

The news from Afghanistan emphasises the need for the Ministry of Defence to act

At first glance, last week was a confusing one for watchers of the defence debate. On the one hand, Afghan President Hamid Karzai announced at a major conference in Kabul that Afghan forces will take lead responsibility for security in that country by 2014, a plan supported by the British foreign secretary. On the other hand, the British prime minister seemed to suggest that the UK's armed forces could begin to withdraw as early as next year.

At the same time, the National Audit Office (NAO) published a report that in effect ordered the Ministry of Defence (MoD) to live within its means, and reduce its planned expenditure over the next 10 years by about $53.35 billion (Dh195.9 billion) in order to do so. Some commentators translated this as, among other things, requiring the Army to lose up to 30,000 of its soldiers. Defence Secretary Liam Fox agreed that his department's current programme was "entirely unaffordable", and floated the idea of cutting the number of senior officers.

How does one make sense of that variety of messages? Well, on Afghanistan, Karzai and William Hague were setting out a plan that, if successful, would see the Afghans essentially running their own country in four years' time. The challenge for the international community, and in particular Nato, is to ensure that the build-up of the Afghan forces, in terms of their quality and quantity, is such that this objective can be achieved.

Concentrating minds

If nothing else, the setting of a deadline will concentrate political and military minds, not only in Kabul, but in Washington, London, Brussels and elsewhere. Should the process go better than many predict, then the withdrawal of some British troops could indeed happen as soon as next year, as suggested by the prime minister. However, should the security transfer take longer, then the objective of handing over responsibility by 2014 would be called into doubt. Although a timeline has been set, this does not replace the over-riding principle that matters will ultimately be governed by conditions on the ground. So a sufficiently secure Afghanistan remains the objective; handover to the Afghans by 2014 is the aspiration. It is at this point that the NAO report becomes important — because the underfunding of British operations in Iraq and Afghanistan has been simply the most visible symptom of the MoD's chronic budget difficulties, and chronic overspending. There were two solutions available: to increase central government funding for current military operations, and for the MoD to reorder its priorities.

Neither has really happened to the degree necessary. In terms of current operations, the Treasury fought the MoD every step of the way, paying what it had to, but on a grudging, minimalist basis. The MoD, for its part, has consistently failed to carry out the necessary re-prioritisation. In particular, although the department officially stated in October 2006 that its highest priority was the achievement of strategic success in Iraq and Afghanistan, its largest spending programmes remained those devoted to other wars that we may or may not find ourselves fighting in the future.

Core spending on Land Forces, which includes the Royal Marines, the Army, and the helicopter and transport parts of the Royal Air Force — the units that were doing the heavy lifting in Iraq and Afghanistan — saw only a minimal uplift. Why else would there have been continuing shortages of helicopters, surveillance equipment to combat the threat of improvised explosive devices, and sufficient numbers of well-protected vehicles, to name but three deficiencies? The NAO was absolutely right to order the MoD to live within its means. That, however, will mean brave decisions and bold cuts, and not just to the number of senior officers.

Taking a gamble

Those who wish to avoid those big equipment decisions would rather seize on the possibility of early withdrawal from Afghanistan in order to make cuts to British Land Forces, and hope that future wars look less like Iraq or Afghanistan, and more like the kind that justify the new, high-tech equipment that has sat so expensively in the Defence Programme for years, in some cases stretching back to the Cold War.

This brings the whole discussion back to the importance of the current Strategic Defence Review. Unless it is underpinned by a proper analysis of the character and nature of future conflict, in order to determine the likely threats to the security of Britain, then future policy will be based upon those cherished equipment programmes, propped up by vested interests but devoid of logical rationale. No one knows what the future will look like, but we certainly know what Afghanistan looks like, and we know we need to get that right. Britain may be able to start withdrawing troops from Afghanistan next year, and be out completely by 2014, but what if it cannot do that? And what if the next war looks similar to Afghanistan, and needs boots on the ground rather than fast jets, tanks, heavy artillery and submarines?

The present and the future of British security and defence needs are all bound up in this review. To fudge the issue on grounds of expediency, rather than basing policy on rational analysis, will simply perpetuate the muddle that has characterised the decade since 9/11. The Coalition has the opportunity to bring clarity and direction. Is it willing to rise to the challenge?

General Sir Richard Dannatt is a former chief of the British Army's General Staff.