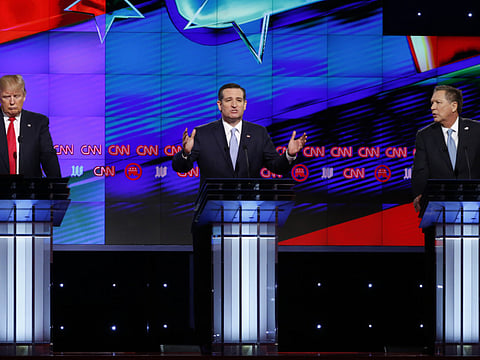

Three candidates, three faces of Republicanism

Kasich, Cruz and Trump offer strikingly different yet coherent world views that draw on the party’s history and traditions

As campaign strategists feverishly draw up battle plans for the next round of Republican primaries, and party chieftains discuss solutions to a possible deadlock, voters can be grateful. In contrast with the last several presidential nomination contests, this cycle is giving Republican voters clear and bold choices.

The three surviving candidates all have strong personalities and distinctive campaign styles. They also offer strikingly different yet coherent world views that draw on the party’s history and traditions. Each presents a different face of Republicanism.

Begin with the front-runner, Donald Trump. Though he is depicted as an interloper — not a “true” conservative — his pitch would have sounded familiar to Republicans in an earlier time. Tune out the bluster and bravado, and you’ll hear the clarion strains of Fortress America nationalism that defined the party from the late 19th century up through the Great Depression.

Trump is a devoted protectionist who wants stiff tariffs levied against unfair competitors like China. His nationalism, more economic than military, is largely directed at allies who don’t pull their weight. This theme isn’t new for Trump, and neither is his aggressive tone. In an “open letter” published in major newspapers in 1987, Trump wrote: “The world is laughing at America’s politicians, as we protect ships we don’t own, carrying oil we don’t need, destined for allies who won’t help.”

He includes a strong dose of anti-immigrant populism in his argument. In this, Trump has a Republican forebear: Patrick Buchanan, twice a Republican candidate for president in the 1990s and a fierce critic of immigration, “illegal” and otherwise.

“Do we have the right to shape the character of the country our grandchildren will live in?” Buchanan wrote in 1994. “Or is that to be decided by whoever, outside America, decides to come here?”

Trump’s appeal is much broader than Buchanan’s. One reason is the growing anxiety that a more diverse America has dispossessed older, white “pocketbook voters” worried about stagnant wages and shrinking benefits. It’s not just Republicans who are fearful. Democrats are, too, to judge from the crossover vote in the Massachusetts primary, much of it evidently going to Trump.

At the same time, Trump has dispensed with the religious and cultural warfare Buchanan was spoiling for, against an array of supposed evils. Trump has shown little interest in exploiting these prejudices. In fact, of the remaining three Republican candidates, he is closest to the mainstream on social issues like abortion and Planned Parenthood.

It is Ted Cruz, the ideological conservative, who wears the armour of the culture warrior. Like Trump, he developed his arguments long ago. As a Princeton undergraduate, Cruz was a protege of Robert George, the political and legal philosopher later appointed to the President’s Council on Bioethics that advised George W. Bush on embryonic stem-cell research.

Cruz combines values conservatism with the “constitutional conservatism” that emerged in the Republican Party in the Obama years when tea party groups and members of the House Freedom Caucus crusaded against the Affordable Care Act. It was not just bad policy in their view, but dangerous federal encroachment into areas not strictly “enumerated” in the Constitution.

Government shutdown

The progenitor is Barry Goldwater, who more than half a century ago came before the nation as a “constitutional fundamentalist,” as the political journalist Richard Rovere wrote at the time. Like Cruz, Goldwater often depicted “big government” as a kind of law-breaking. “I will not attempt to discover whether legislation is ‘needed’ before I have first determined whether it is constitutionally permissible,” he stated in his book, The Conscience of a Conservative, published in 1960.

tirelessly reiterates his faith in “conservative principles” while showing little interest in making policy. Consider the episode that made him famous, the government shutdown he led in 2013. It began as a protest against the continued funding of Obamacare. Yet, Cruz himself has yet to propose a detailed health-care plan of his own.

In debates, Cruz talks less about what he will do as president than about the many things he will undo. The list includes “every illegal and unconstitutional action taken by Barack Obama”.

This leaves the one policy wonk still in the field, John Kasich. Like Trump and Cruz, he developed his ideas long ago. Kasich was an energetic member of the House of Representatives in the 1980s and 1990s. In those years, the Beltway didn’t seem a den of corrupt insiders, but a hive of conservative “policy intellectuals” — at the time a new expression — who populated congressional staffs and think tanks. Coming into power after a long period of liberal dominance, they were eager to test out new conservative approaches on crime and welfare, poverty and health care, among other issues.

Kasich, the policy conservative, remains a pragmatist. He was one of a handful of Republican governors who accepted the federal Medicaid expansion offered under Obamacare, in defiance of party orthodoxy.

Not that Kasich is a moderate. True to his origins, he advocates major tax cuts and supports a balanced-budged amendment, top items for conservative policy thinkers in his congressional years. Announcing his run last summer, Kasich said: “Policy is far more important than politics, ideology or any of the other nonsense we see.” In 2012 such words might have doomed him — unless he repented, as Mitt Romney did. Kasich remains the darkest of horses. Yet, he could be a powerful player this summer, if neither Trump nor Cruz sews up the nomination.

Meanwhile, with many more primaries and caucuses to go — in important battlegrounds like New York, Pennsylvania and California — the differences among the three candidates should sharpen.

Party elders who rue the election that got away from them have missed the bigger message. The Republican “base” is not so easily categorised — or pandered to — as in past years. Voters have lost patience with litmus tests and talking points. They want arguments. Now they are getting three very different ones.

— Bloomberg

Sam Tanenhaus is the author of The Death of Conservatism and Whittaker Chambers.