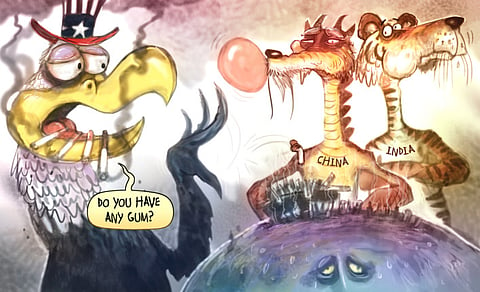

The world’s climate is in the hands of just three nations

If India, China and the US work together, there is hope after the Paris climate summit

While all contributions from the 195 countries at the UN’s global climate change summit in Paris will be important, three are critical. China, the United States and India hold the key to large-scale global progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

So far, the UN climate process has faced the challenge of rallying all countries behind one unified resolution. While this remains crucial, efforts to build global consensus are increasingly varied, emphasising the role that multilateral, national and subnational policies can play in responding to the unique circumstances faced by societies around the globe. The Paris meeting reflects this shift, as the UN increasingly looks to shape the individual national commitments of countries around the world into a new, dynamic global compact. This approach creates encouraging possibilities for China, the US and India — which together make up roughly 40 per cent of global carbon emissions — to become global leaders in a new and more sustainable energy future.

The US and China have proved that real progress can be made on climate both nationally and through bilateral cooperation. The two countries have converged significantly over the past two years, embracing goals for reducing emissions, raising energy efficiency standards and expanding renewable energy deployment in the near and long terms.

A climate agreement between the two countries in November last year and further actions announced during Xi Jinping’s recent state visit to the US signal the Obama administration’s intent to dramatically lower the carbon footprint of America’s energy sector before he leaves office. It also reaffirmed President Xi’s resolve to lower carbon emissions.

These agreements have substance: the US has pledged to reduce emissions by 26-28 per cent compared with 2005 levels, while China has committed to peak emissions and increase the non-fossil fuel share of its energy mix to 20 per cent by about 2030. Both sets of commitments have been incorporated into their countries’ national contribution for Paris.

China intends to shift away from its heavily industrial, carbon-intensive economy to a more diversified, sustainable model. Its new economic strategy emphasises a service sector and advanced manufacturing that leave a smaller carbon footprint. It also focuses on industrial and building efficiency to reduce carbon intensity. Moreover, it incentivises wider adoption of electric vehicles. These, if fully implemented, will have a significant global impact.

India is the world’s third largest emitter and, as with China, its climate strategy must be seen through the lens of its economic strategy. In contrast with China, India’s economic challenge is to reduce its reliance on the service sector, and to invest more in its core transport, industrial and energy sectors.This, in fact, creates an enormous opportunity to drive smarter and more energy-efficient investment, including in the world’s best, low-carbon infrastructure and energy technologies. Working together, China and India could significantly increase renewable energy deployment worldwide, as in the Sino-Indian agreement in May that resulted in a $22 billion investment in new energy projects, including possible Chinese investment in photovoltaic industrial parks in India and on broader R&D cooperation in renewables sectors.

India and the US likewise agreed to a range of cooperative clean energy projects in January this year. Under the US-India Partnership to Advance Clean Energy, these projects saw a joint commitment to advance research and development, clean energy and finance mechanisms, and cooperation on appliance efficiency and clean energy storage. While India still faces challenges in lowering the cost ofcapital for renewable energy projects and delivering clean electricity to many of its poorer rural areas, these bilateral agreements indicate measurable progress in the long march towards sustainable energy use.

This is a promising time for developing countries like China and India to forge a low-carbon economic pathway. Unlike the US during its industrial heyday, they can capitalise on the effective and affordable energy technologies widely available to accelerate their energy transition. Such a move would be a boon to the global clean energy business, including the US — home to the majority of clean energy patents. These must be developed and brought to market as a matter of global urgency.

But to make real progress the US, China and India must direct more publicand private resources to the climate challenge. Less than 2 per cent of global public research and development dollars are spent on renewable energy — a paltry $5 billion in total. China, the US and India could show global leadership by directing, say, 5 per cent of their public research and development budgets towards climate challenges. All three should also collaborate to leverage enormous private sector investment in new energy technologies and innovative infrastructure projects that reduce the global carbon footprint.

What happens in Paris is critical in developing a global climate framework to keep temperature increases within 2C. More critical again is what happens after Paris to give effect to this framework on the ground.

If the US, China and India develop cooperative climate change strategies — including strong financing models — the “big three” can help bridge the divide between the developing and developed countries involved in climate negotiations. Alongside the many challenges, there is historic opportunity.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd