Karl Marx once said: “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce.” Yet with hundreds of thousands having lost their lives already, and millions more displaced, there is nothing farcical about the Syrian tragedy, which has raged on since 2011.

A lot of ink will be spilt in the coming years and decades, and many historians, journalists and former officials from around the world will dedicate their entire careers to studying and analysing how Syria — and the world — sleepwalked into the first major calamity of the 21st century. Many will point fingers, while others will try to seriously understand the root causes and motives of such an uncharacteristically devastating conflict. Most of those historians, writers and pundits will make at least one reference to the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916.

At the height of the First World War, France and Britain saw an opportunity to enlarge their empires at the expense of the collapsing Ottoman one. The interests of the people of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Anatolia were never on the minds of French and British (and before 1917, Russian) strategists and diplomats during the Sykes-Picot discussions, named after Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot, and in the sequence of conferences and agreements that followed.

The secular French Republic sought to carve out a Christian entity in the form of Greater Lebanon, using Catholic links as a bridgehead into inner Syria. The British hardly cared about Mesopotamia’s civilisational heritage, but they did crave what was beneath its soil — the vast reserves of oil much needed for an ever-expanding fossil-fuel-based global economy. The Russians cared little about the fate of either the Kurds or the Ottoman Empire.

The Tzarist regime, however, wanted to amputate its long-standing imperial nemesis by carving out as much territory as possible, handing it over to the burgeoning nationalist forces in Anatolia — while ruthlessly repressing such forces at home.

The aim was to restrain the ambitious Turks in a tight Anatolian box and insure Russia’s mastery over sea routes to warm waters; but Lenin’s revolution was quicker and the Romanovs’ part in the Great Powers deal never came to be. The Sykes-Picot blueprint was tweaked and re-tweaked on several occasions between 1916 and 1923 to account for the changing circumstances on the ground. When Russia’s Bolsheviks abrogated from the Great Power scene, France and Britain scrapped the promised Kurdish national homeland to placate the newly born (and very combative) republican regime in Turkey. Syria was further split into smaller entities as the French realised the daunting challenges they faced.

The Christian-dominated Lebanon was enlarged to include the fertile Bekaa and Akkar plains, inhabited by a majority of Muslims — setting on course a dynamic that would eventually lead to a devastating 15-year civil war in Lebanon.

The British traded a 25 per cent share of Iraqi oil to the French in order to get the until-then Syrian city of Mosul, which was floating atop a sea of fossil fuel. And in 1939, France handed the Syrian Hatay province, and the city of Antioch (the capital of Hellenic Syria) to Turkey — once a German ally — in order to placate the Kemalist regime as the Nazi tide swept across Europe.

Behind closed doors

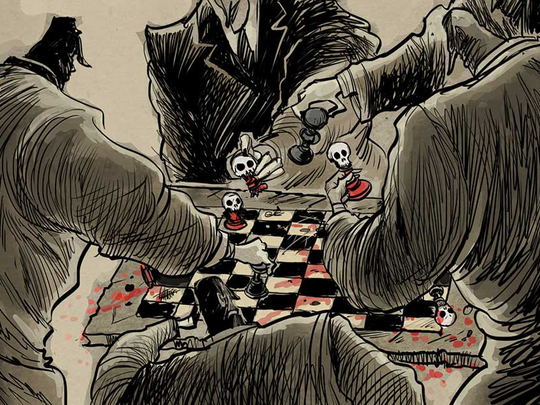

A century later, Syria is once more a playground for the Great Powers, and although the script may have varied, the dynamics have hardly changed. One major difference, however, is that regional powers are now awakened and have developed their own schemes for the troubled Middle East, at times challenging the will of the established world powers. Russia and the United States, in addition to Saudi Arabia, Iran and Turkey are all interlocked in a mortal struggle over the lands extending from Mosul to Beirut, and from Aleppo all the way to Basra. We are mostly unaware of what the diplomats and planners are discussing behind closed doors, but one can nonetheless speculate.

The Russian craving for the warm waters of the Mediterranean has not abated, as their fighter planes and warships cruise the Syrian shores on an hourly basis. And the old Romanov desire to curb Turkish influence in the Caucasus, the Middle East and Central Asia was also revived by Putin’s Kremlin. The Kurds, once again, play a central role in the Russian plan to disrupt Ankara’s bid for regional mastery. The Kurdish question left unsolved by the treaty of Lausanne in 1923 — an offspring of Sykes-Picot — has definitely made its way back on to the tables of Russian and American planners.

The Americans seek to benefit from the regional convulsions to further their presence in the region — and especially to keep a watchful eye on Iraq. Mosul is once more at the heart of the issue. Liberating Mosul from Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic state of Iraq and the Levant) is not an impossible military task, yet the question of who should control Mosul is still open. The US wants a foothold in Iraq, and a ‘Sunni’ entity with Mosul at its heart seems ideal for checking Iran’s attempt to extend its clout over Iraq and into the Levant. Turkey and Iran on their part are emerging powers in a collapsing milieu, and they will resist every attempt on the part of the international powers to deny them the benefits of this historical moment, or to extend the chaos across their borders.

The diplomats and the planners are quite busy today, drawing and redrawing maps, moving pieces across the regional chessboard. At the same time, the voices of the people of Syria remain unheard. And if these dynamics persist, this century will not unfold very differently from the one before it… all at the expense of our future generations.

Fadi Esber is a research associate at the Damascus History Foundation, an online project aimed at collecting and protecting the endangered archives of the Syrian capital.