The romance of libraries

Despite the strong monopoly of internet, revival of public reading places is possible

Public libraries in the West have had another bad year. They have become like local railways. People like having them around, and are angry if they close. But as for using them, well, there is so little time these days. The latest Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy figures on library closures are dire. In the past five years, 343 have gone in the United Kingdom. Librarian numbers are down by a quarter, with 8,000 jobs lost. Public usage has fallen dramatically. Book borrowing is plummeting, in some places by a half.

The admirable children’s laureate (and cartoonist) Chris Riddell said during the latest campaign for libraries that, “if nurtured by government, they have the ability to transform lives. We must all raise our voices to defend them”. But what sort of library are we defending? I’m not sure the fault in this lies with that easy target, the government, nor even in the once-gloomy fate of the book.

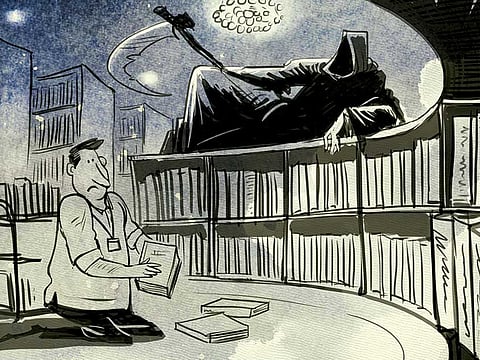

Last week, I was in my excellent local library and it was near empty. The adjacent Waterstones was bursting at the seams. I know it was Christmas, but something tells me there is a problem with libraries, not with books. When an institution needs a luvvie-march to survive, it looks doomed. I was a library addict. I grew up mooching along the shelves of my local branch, feeding on its fantasies of biography, travel and self-help. I was terrified alike of the bespectacled librarian and the tramp behind the Times. When I found vinyls and CDs could be borrowed for free, I was over the moon. But I felt as the Victorians did of library fiction. Should so much pleasure be offered “on the rates”?

The story of the library is the most exhilarating in modern culture. To US historian Matthew Battles it is a metaphor for the land of opportunity, a place where, “lost in the stacks”, new Americans could “dream of personal success, unaided by unnamed others, a stage with a mirror for backdrop that reflects only the reader”. In Britain, the library was a grammar school without an 11-plus, a teach-yourself academy, a democracy of learning.

The most exciting book on my shelf is Great Libraries of the World (the finest being in Portugal’s Coimbra). One day, I shall try to see them all. Battles admits digitisation has changed everything. The public library is no longer a church sacred to knowledge. Its walls have been blasted open, its uniqueness gone. It cannot live in a romantic past, a place where books go to die. Nor need it. So much rubbish is said and written about the death of books. Five years ago, when Amazon ebook sales overtook those of paperback copies, it was assumed the book was doomed. Print was yesterday, one more victim of the great digital wipeout.

I have an entire file of obituaries of the book. In the event, as with most over-hyped innovations, ebooks have found a sound place in the market, but hardly a prominent one. Waterstones last year stopped selling Kindles and switched the shelf space to books. It saw a 5 per cent rise in sales. After years on a plateau, physical book sales have begun to rise again. Though the bookshop has suffered, the book has not.

Place of congregation

But these are buyers, not borrowers. The library must rediscover its specialness. This must lie in exploiting the strength of the post-digital age, the “age of live”. This strength lies not in books as such, but in its readers, in their desire to congregate, share with each other, hear writers and experience books in the context of their community. Beyond the realm of the digital oligarchs, the big money now is in live. It is in plays, concerts, comedy, lectures, debates, gigs, quizzes, performance of every sort. London must have more live events today than ever in history. Who would have dreamed that retiring politicians would grow rich not on banking but on public speaking?

The local library needs to become that place of congregation. It should combine coffee shop, book exchange, playgroup, art gallery, museum and performance. It must be the therapist of the mind. It must be what medieval churches once were. Indeed the decline of libraries has a similar trajectory to that of churches, thousands of which now lie actually or virtually unused in villages and towns across the land. They too have underused buildings and underused books. Like libraries, they must turn to communal nostalgia for support. Libraries and churches have a shared metaphysic. They embody the cultural identity of a place as its archive, museum and collective memory.

I remember once visiting Blickling church in Norfolk during a festival. Some inspired individual had asked every local organisation, from the Scouts to the lifeboat to the second-hand bookshop, to display its wares in an aisle bay. The place was packed. It was a virtual high street. There was even room in the chancel for choir practice. Since redundant churches are prominent buildings, and most cannot be demolished, they offer the perfect venue for the new library as cultural hub. In some cases, churches are already being used as one-stop refuges for high streets in decline, from post offices and corner shops to nursery schools and clinics.

Ailing libraries should be removed from their present owners and managers and be vested in neighbourhood town councils, as is common on the continent. There will be thrills and spills, but local responsibility is the only secure way forward — and it would raise money.

Ever since the days of Alexandria, the library has been the palace of the mind, the University of All. The internet has removed its monopoly on knowledge, but cannot replicate its sense of place, its joy of human congregation. The Victorian tycoon Andrew Carnegie, first great patron of public libraries in Britain and America, dreamed of one in every town and village. His vision awaits renaissance.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Simon Jenkins is a prominent journalist and author. His recent books include England’s Hundred Best Views, and Mission Accomplished? The Crisis of International Intervention.