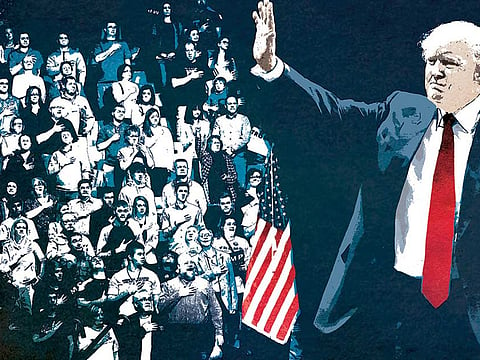

The crowds still love Donald Trump

Although the ‘Trump doctrine’ is being copied around the world, it has a possible expiry date: The US midterms in November

‘Even these horrible, horrendous people,” the president boomed, pointing at the assembled press, “they say, probably in the history of this country, maybe in the history of the world, there has never been anything like what happened in November of ‘16”. A rare accurate insight from the man who, since he took office, has uttered 4,229 false or misleading statements, according to the latest tally by the Washington Post.

Speaking at an event to support a Republican candidate for the United States Senate in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, US President Donald Trump was in his element. He railed against “fake, fake, disgusting news,” complained about the “Russia hoax” and reminisced about election night. These rallies are his happy place; recall that, in the chaotic days after his win in 2016 when there was an administration to form, all he really wanted to do was get back out on the trail.

Beyond the rallies, Trumpism continues apace, a potent cocktail of economic nationalism, opposition to immigration and vicious attacks on his opponents. Its twists and turns don’t seem to hurt Trump too much; his approval rating remains around the 40 per cent mark, and has improved significantly since the winter. As a side note, it remains extraordinary just how much the president is motivated by a loathing of his predecessor: Last week, the White House announced that it would scrap Barack Obama-era rules, forcing auto companies to make vehicles more fuel-efficient and less polluting. Unbelievably, the changes were billed as “Make Cars Great Again” by Trump’s Transportation Secretary. And last Monday, the president seemed to indicate that his trashing of the Iran nuclear deal in May was less about principled opposition than the fact that Obama did it. “If [the Iranians] want to meet, I’ll meet anytime they want, anytime they want,” he said.

After nearly two years, not only are we getting used to Trumpism, we are getting used to it being admired across the world. In Europe, his fans include anti-immigrant stalwarts Geert Wilders, Marine Le Pen and Nigel Farage. Crucially, more mainstream politicians look favourably on his tactics, too. While still being the United Kingdon foreign secretary, Boris Johnson admitted he had become “convinced that there is method in [Trump’s] madness”. Imagining the president negotiating Brexit, Johnson said: “He’d go in bloody hard ... There’d be all sorts of breakdowns, all sorts of chaos. Everyone would think he’d gone mad. But actually you might get somewhere.” Johnson, a clear favourite of Conservative party members, is still very much in the running to be the next prime minister of Britain.

Global sea-change of opinion

The exportability of the “Trump doctrine” derives largely from the impression left by his shock win in 2016. Despite the fact he lost the popular vote, that victory has been styled as part of a global sea-change of opinion: Voters delivered their verdict on the centrist, technocratic politics that had become the norm in advanced democracies, and it was presented as decisive. Trump rode a wave of resentment to power with an eccentric formula that nonetheless achieved success. A formula that could be copied.

Apart from a few special elections, voters have yet to deliver a verdict on his performance as president. When this comes, in November, it will have importance way beyond America’s borders.

The candidate Trump was supporting on Thursday night in Pennsylvania was Lou Barletta. He takes a hard line on immigration, opposes Obamacare and supports import tariffs. Yet, he is trailing his democratic opponent Bob Casey by around 15 percentage points. Casey has an incumbent advantage, but if Trump’s buddy can’t win in the state that did so much to help secure the White House, perhaps the formula isn’t so brilliant after all (a special election in rural Pennsylvania in April resulted in a shock win for the Democrat Conor Lamb).

This year’s midterm electoral map is a tough one for the Democrats. They could flip the house, where all 435 voting seats are up for election, and a net gain of 24 would make it theirs. The Senate will be much harder: Democrats must defend 26 of their 49 seats, Republican 9 of their 51.

If the results of midterm elections to the House and Senate are good for the Republicans, that would cement the view that Trumpism is a vote-winner, and an appropriate response to the political times we’re in. If they aren’t, then the bubble might just burst, with global implications. As the man himself might put it: Who wants to copy a loser?

— Guardian News & Media Ltd