Telling NHS doctors to go home is self-harming madness

Why would anyone — let alone a health secretary — insult the one-third of Britain’s doctors who were born abroad by suggesting that they’re only ‘interim’?

A wise government facing the multiple threats of Brexit would strive in every way to mitigate its worst effects. Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer dashed to Wall Street on Thursday to try to calm markets as the pound fell again and future investment to Britain was in jeopardy: The idea of Philip Hammond on a “charm offensive” may be a tad improbable — but at least he’s trying. Not so the British prime minister, home secretary and health secretary, though: In a hole, they keep digging.

They are right that immigration must be addressed when every poll and focus group showed it was at the heart of the Brexit vote — but what kind of immigrants? If there is “good” and “bad” migration, doctors, nurses and care workers would surely top the “good” list. So would students swelling university coffers, returning home to influential jobs with a fond connection to Britain spreading our soft power round the world. Yet, they have picked on both these groups this week in a fit of self-harming madness. The popular anti-immigrant fears that stirred European Union (EU) antagonism were scenes such as the 4,000 people a day now struggling to the EU in boats or the east Europeans packed into slum housing by gang masters serving car-washes and farmers.

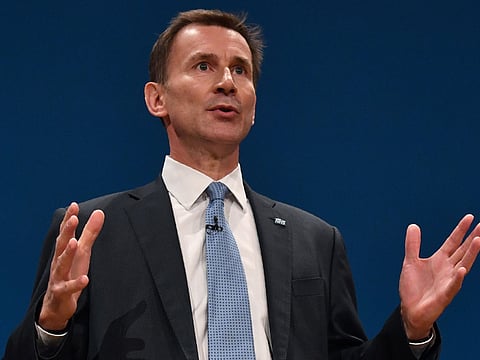

But why pick on doctors at a time of severe shortage, when some units are closing for lack of qualified medics? Everyone welcomes Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt’s announcement of 1,500 more medical school places by 2018. When Britain needs more doctors, it makes no sense to turn away so many able applicants. Though somehow it has slipped Hunt’s memory that his government cut medical training places by 2 per cent in 2012, and only last year cut the Health Education England budget for training.

The puzzle is why anyone would insult the one third of National Health Service (NHS) doctors born abroad by suggesting they are only “interim”, as Prime Minister Theresa May said. Britain needs both homegrown and foreign staff, all it can find, scouring the world for more. Since the Brexit vote, agencies are struggling to recruit nurses and doctors abroad. As ministers refuse to guarantee the right for EU staff to stay, NHS doctors and nurses feel insecure and unwelcome — and many may slip away. Ed Smith, chair of NHS Improvement, the regulator, writes in the Telegraph warning of the risk to patients if overseas staff are made to feel “demoralised and diminished”.

Simon Stevens, head of NHS England recently wrote that “It should be completely uncontroversial to provide early reassurance to international NHS employees about their continued welcome in this country”. Hunt’s claim that Britain will be “self-sufficient” in medical staff is nonsense — and he knows it. These new doctors won’t qualify as consultants until 2030, while everywhere has ageing populations and the World Health Organisation estimates a global shortage of two million doctors.

The number of people in Britain over the age of 85 will double by 2037 — and who is to care for them if Britons chase away all foreigners? At the same time, Hunt squanders the British-born who are there: Around half of medical students don’t go into the NHS when they qualify. Hunt is right to oblige them to pay back with four years’ service to the NHS — but that’s not enough and it’s only necessary because of all he has done to alienate junior doctors instead of wooing them to stay for life. Treasuring them, begging them not to depart for easier work in Australia would be economic prudence. Scaring away the foreign-born doctors will do untold damage.

The NHS has lost a decade in progress, returning to where it was 10 years ago in A&E-waiting and ambulance-response times. Waiting lists for operations are at their highest since 2007.

The social care calamity in local government has helped tip the NHS into crisis — a crisis happening right across the UK, where doctors are needed everywhere. More than 60 per cent of care workers in London are foreign-born, mainly from outside the EU, people May could have banished long before Brexit. But the government knows that if it drives out cheap foreign care-labour it will need to pay higher rates with better conditions to attract British-born staff.

Good idea, but will they raise the tax to do it? Paeans of praise poured from the prime minister in her speech on Wednesday, bidding to be the party of the NHS. But she showed no sign of confronting the NHS crisis. Instead, it was a Go Home message to invaluable NHS and social-care staff. She looks and sounds like a safe pair of hands — but we may find her neither as practical nor as competent as she pretends.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Polly Toynbee is a columnist for the Guardian. She was formerly BBC social affairs editor, columnist and associate editor of the Independent, co-editor of the Washington Monthly and a reporter and feature writer for the Observer.