Sitting on a volcano of public discontent

Bouteflika's regime has indoctrinated Algerians to think of the Arab Spring as a threat, but the young population will not be fooled forever

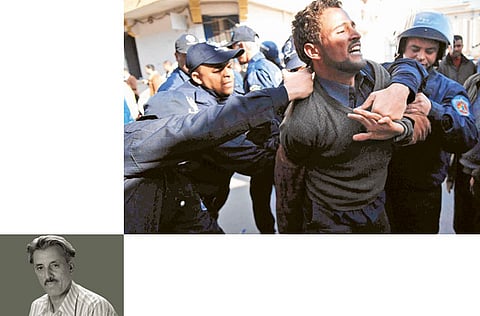

Less than a year after the start of the Arab uprisings, Algeria appears insulated from political upheavals experienced by other countries of North Africa, such as Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Morocco. Algeria experienced nationwide riots in early January 2011 and in the context of the Arab Spring, several members of civil society and historical personalities have raised the prospect of a peaceful change in Algerian politics. Nevertheless, despite the lifting of emergency rule in late February, the Algerian regime seems to have no inclination to change. Algeria faces institutional obstacles to democratic change, say some observers. It's as if nothing has happened, said Le Monde, the famous French newspaper.

The wave of revolts shaking the Arab world since the beginning of 2011 seems to have left Algeria untouched. Yet the Algerians share the same aspirations as their neighbours — Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco — which rose up to demand more democracy and the end of social deprivation (unemployment, health and education).

The first electoral foray in Algeria since the wave of Arab Spring, the May 10 parliamentary elections, produced a result almost identical to the 2007 elections, according to results released last Friday. The National Liberation Front (FLN), which has dominated the political scene since independence and which is also the party of President Abdul Aziz Bouteflika, retains control of the National Assembly. Algeria would be, if one believes official figures, tightly windproofing itself against change blowing across the Arab and Muslim world.

The elections held last year in Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt produced assemblies dominated by Islamists. In Algeria, on the contrary, Islamist parties have fared badly. The FLN and its ally, the National Democratic Rally (RND) party of the prime minister, together won an absolute majority with 288 seats out of 462, including 220 for the FLN.

Spectacular setback

The Green Alliance, a coalition of three Islamist parties, came third, with only 48 seats.

The setback was so spectacular that it was immediately dubbed suspicious, especially as initial estimates suggested that the Islamists would capture second place. The Green Alliance denounced a "massive fraud" and announced its intention to file an appeal with the Constitutional Council.

These charges may be tempered by the abstention rate, which remains high (57.6 per cent, and up to 80 per cent in Kabylie region) even if it is less than the record of 2007(64.4 per cent).

Consistently, the Algerian government, on its part, advanced a simple explanation for the stability of the electorate: the deep trauma of the civil war of the 1990s, after the victory of the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) in the election of 1991, interrupted by the military and, more recently, the confusion in Egypt and Libya which has surprised Algerians.

The distribution of oil revenue, through which the regime was able to give the public a series of welcome reliefs when the Arab Spring threatened to spread to Algeria in 2011, is another stabilising factor. It is not clear, however, that these devices will permanently immunise Bouteflika against real protests at the presidential election falling in 2014.

The elections of May 10 produced another Algerian specificity, which was much more positive: the massive influx of women in parliament, following the introduction of quotas in electoral lists. They will now be 145 in number, or nearly one-third of the deputies in the new Algerian Assembly.

The overall strategy of Algeria, since last year, is to disarm the Islamists, and then coerce them to enter the game of specific democracy: one does not throw the Islamists to sea, but intends swimming with them! In Algeria, for the past three months, the regime has approved a dozen parties to better project the multi-party system. It also uses the forbidden word ‘Islamist' on TV and speaks of it as a healthy part of nationalism and ‘anti-Spring' Arabic nationalism.

There is constant reminder by the FLN and the alliance that revolution is chaos or Nato. Therefore, the plan is to hold elections with international observers and the slogan that ‘if you do not vote, it will be recolonisation, like Libya'. This stance is also a reminder of the values of the Liberation War.

The images of chaos in Libya, those of false consensus like in Morocco and the slow Iranianisation of Tunisia, have had their effect: the Algerians now speak of the Arab Spring as a threat, not as a possible revolution to free themselves. But all said and done, the Algerian regime underestimates the Arab Spring and forgets it has had the first aborted spring of its kind in the Arab world.

Many days ago, an Algerian official presented the Arab Spring as a disaster for the Arab nation and the Arab world. The Algerian official forgets that the system of military rule was the first aborted spring in the Arab world, after the Algerian people had made the greatest revolution against the French occupation.

The complicity of the West, especially France and the US and the FLN, and with the generals against the will of the people, was exposed.

In the wake of the Arab revolutions, several reforms have been undertaken. These must be passed before the legislative elections of 2012. It is useless to rebel against the Father of the Nation only to submit, at the end, to the Imam of the Nation, whisper the soft voices of past dictatorships. The fact remains that socially, economically and politically, Algeria is sitting on a volcano and many people, including those within the regime, fear an explosion. Seventy per cent of the Algerian population is under 30 years of age.

Reeling under the impact of the clash of generations, changes in the medium and long-terms are unavoidable.

Shakir Noori is a journalist and writer based in Dubai.