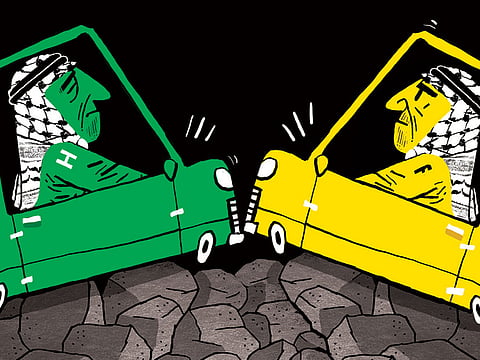

Rocky road for Fatah-Hamas unity deal

Dismantling of security apparatuses in Gaza will be a major sticking point in arriving at a reconciliation agreement

The stop-go diplomatic Fatah-Hamas reconciliation deals going on for the best part of a decade maybe reaching their conclusions with a copper-coloured seal between the two Palestinian movements over a unity government that would rule the West Bank and Gaza.

Whilst many would say I heard that before — after all negotiations took place in Makkah in 2007, Cairo in 2011, Doha in 2012 and other places and came to naught — this time it is for real, well almost. Cairo has been working hard and pushing to iron out a deal, one to satisfy everyone, and it seems we have a winner.

On the face of it, Hamas is no longer adamant about ruling Gaza. For the first time since 2006, when it retreated to the Gaza Strip, it is relinquishing rule and acquiescing to the Ramallah-based Palestinian National Authority (PNA). This time, and again on the face of it, there will be one government and one voice to speak on behalf of the Palestinians. No more splits on the basis of geography, no more harangues.

Great. So what is the problem? Well, it’s not really a problem, only a tingly feeling on the part of Hamas, no Fatah as well, no Hamas, no Fatah! The arguments can go on and on if you allow them for there is much still at stake. For now, Hamas has agreed to give up its dominant-rule status and Fatah wants to extend its PNA-rule, but doesn’t want to finance a Gaza administration that would continue to be loyal to Hamas.

For the time being, the nitty-gritties have been pushed aside, to be negotiated later at an appropriate time. Afterall, Hamas has been ruling Gaza since 2007. PNA’s chief negotiator Palestinian Azzam Al Ahmad has tried to whitewash the issue. He said simply the Palestinian unity government of Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah will be expected to officially take over the Gaza Strip on December 1, 2017, and will put its guards on the Rafah crossing.

The unity government already established a symbolic presence in Gaza with the prime minister visiting the strip soon after the deal was signed on October 12, 2017, in Cairo with Hamas chief negotiator Saleh Arouri. It was a roaring affair. Everyone, politicians on both sides, Hamas and Fatah, including Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas — who had called the deal a “final agreement to end the division” — displayed an unusual confidence that things will be green around the corner this time.

Unlike previous reconciliation attempts, Hamas leaders are now more open. Despite his radical credentials, Yehia Sinwar, the new Hamas leader who was elected to lead the Islamist organisation in the strip, had for long displayed much pragmatism about the way forward. Arouri too made no bones about it saying “... We have adopted the strategy of one step at a time so that the reconciliation will succeed”.

But, and it’s a big ‘but’, many in the international community have their hands on their hearts. The one-step approach could be seen as problematic and non-committal. Behind the razzmatazz, many fear the most fundamental issue, that of disarming Hamas and its security forces, like the 25,000-strong Al Qasim Brigades, are still under negotiations. They have been left to the next round of talks between Hamas and Fatah on November 21.

The brigades are only part of the Hamas security structure that includes five security apparatuses of the intelligence service, internal security, national security forces, police and civil defence. What is to become of these will likely be an intense subject of discussion and could possibly tear the reconciliation process apart. These only number 14,000, in addition to the 23,000 government employees. What would become of them is likely to end up as ‘power play’ and ‘bargaining chips and pleas’ within the Hamas-Fatah logistics.

So, it would probably be a long process of change, and the November 23 meeting, if it isn’t crushed in its cradle, is likely to result in a series of many such meetings, because over the last 10 years and in addition to separation from the PNA and the Israel-imposed blockade on the Gaza Strip from 2007 onwards, Hamas has built a significant organisational and security infrastructure to reinforce its status and authority. Dealing with this, for it to be integrated with the PNA administration, will likely be a complex undertaking that would require an enormous goodwill on the part of Hamas and the PNA. If the goodwill is here now, starting at point-zero of the implementation process, will it be later on that Hamas personnel could be forced to be curtailed or down-sized?

The road ahead is likely be tricky and filled with pitfalls especially in the light of the fact that Abbas has already made it clear he will not accept a Hezbollah-style Hamas organisation with its paramilitary units, as is the case in Lebanon. So there is still a good deal of negotiations to be had to produce a concrete agreement acceptable to all, especially, since at the other side of the equation, there is Israel — already demanding that Hamas explicitly recognise its existence and disarm itself. The recent changes in the Hamas charter made in May 2017, accepting a two-state solution based on the 1967 borders, and in line with the position of the PNA, is not sufficient in itself, for the Zionist state.

So to use the term of Arouri, it’s still “one step at a time” for everyone. It’s clear, however, that Hamas is moving for change in approach, recognising the fact that this will be the only possible way to get things moving and force Israel to lift the inhuman siege. Yet, this is complicated story in itself, where further guarantees will be demanded on the part of Hamas, the least of which is ending its chequered history with Iran.

Reconciliation is only the beginning of the exercise. What is feared is that Palestinians will continue to bear the brunt of the Israeli siege for quite some time, something that Egypt, as a sponsor of the reconciliation talks, could play a strong hand in persuading Israel to lift quickly.

Marwan Asmar is a commentator based in Amman. He has long worked in journalism and has a PhD in Political Science from Leeds University in the UK.