Quebec G7 the toughest summit in years

The alliance’s involvement in a multitude of geopolitical dialogues is not without controversy

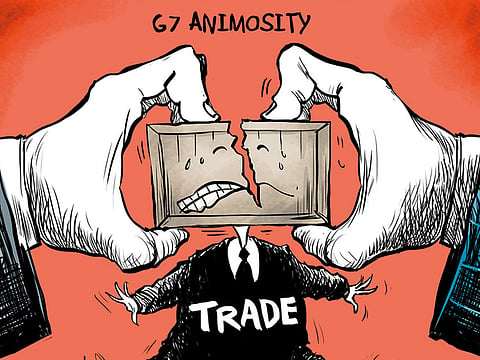

The G7 finished up on Saturday in Canada after one of the group’s most challenging summits. Far from serving as the latest annual affirmation that key western powers are aligned, the session showcased significant splits and occasional remarkable personal animosity between US President Donald Trump and other leaders.

On a range of issues from trade to climate change and Iran, the US president — who made a pre-scheduled decision to leave the summit in Quebec early on Saturday — appears to be dividing from G7 partners at a time of significant geopolitical and international economic turbulence giving rise to talk of a “G6 plus 1”. And this shift was given added spice in recent days by a spate of undiplomatic language, including Trump’s characterisation of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau as “so indignant” while the latter called the US president’s trade tariffs “laughable”.

To be sure, G7 policy fissures did not begin with Trump’s election in 2016, but they have been exacerbated by it. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, there have been a series of intra-western disagreements, from Middle Eastern issues — including the Iraq war opposed in 2003 by France and Germany — through to the rise of China with some European powers and the United States having disagreements over the best way to engage the rising super power.

Yet, despite occasional discord, G7 states generally continued to agree until the Trump presidency around a broad range of issues such as international trade; backing for a Middle Eastern peace process between Israel and the Palestinians along Oslo principles; plus strong support for the international rules-based system and the supranational organisations that make this work. Yet today, more of these key principles are being disrupted if not outright undermined by Trump’s agenda.

Take the example of international trade which saw Trump isolated in Canada following the US imposition of tariffs on steel and aluminium imports against all its G7 partners. The tensions over trade are especially salient for the G7 hosts Canada given that Trump also warned, again, last week that he is considering scrapping the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta).

In this contentious context, Trudeau pushed an agenda at the summit that included trade, tackling income and gender equality, female empowerment, climate change, and peace and security. With the Trump tensions, discussion over numerous of these issues was stymied — as proved the case last year at the Italian-hosted event too.

In this atmosphere of discord, significant emphasis was put at the meeting on finding greater G7 consensus on a range of security and geopolitical issues. Examples here included the upcoming Singapore summit between Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, plus the continuing clampdown against Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) in Syria and Iraq.

Despite Trump calling Friday for Russia to be allow to rejoin the group (as the G8), as was the case from 1997 to 2013, G7 leaders called for a “rapid and unified” response to malign international interference, including by Moscow, such as cyber and chemical weapon attacks like those recently in Salisbury, England. Despite the US president’s desire for warmer ties with Vladimir Putin, there is little sign that Russia will be invited back to the club any time soon after being told it can only rejoin if “it changes course and an environment is once again created in which it is possible for the G8 to hold reasonable discussions.”

The G7 also expressed concerns over the process leading to the re-election of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro. Western leaders remain worried about the destabilising geopolitical and economic impact of the Caracas crisis for the wider region, including bordering states of Brazil and Colombia, and the fact that Venezuela is the third-largest oil exporter to the United States and has the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

The G7’s emphasis on such issues underlines, yet again, the group’s often under-appreciated importance as an international security linchpin — despite the fact that it was originally conceived in the 1970s to monitor developments in the world economy and assess macroeconomic policies. Last year’s Italy summit, for instance, was dominated by the aftermath of the Manchester terrorist attacks and development of a new G7 terrorism action plan; plus the-then brewing nuclear tensions on the Korean peninsula. In Italy, Trump also pushed other G7 members for Nato to become a full member of the global coalition against Daesh.

The G7’s involvement in this multitude of geopolitical dialogues is not without controversy given its original macroeconomic mandate. For instance, China strongly objected to discussion of maritime security in Asia at the 2016 Japan-hosted summit.

It is sometimes asserted, especially by developing countries, that the G7 lacks the legitimacy of the UN to engage in these geopolitical issues, and/or is a historical artefact given the rise of new powers, including China and India. However, it is not the case that the international security role of the G7 is new.

An early example of the linchpin function the body has played here was in the 1970s and 1980s when it helped coordinate Western strategy towards the then-Soviet Union. Moreover, following the September 2001 terrorist attacks, the then-G8 (including Russia) assumed a key role in the US-led ‘campaign against terrorism’.

Taken overall, this year’s G7 saw significant splits, especially on trade. While some of these fissures pre-date the Trump presidency, his agenda has grown these gaps into what could soon become unprecedented strains in the western alliance.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.