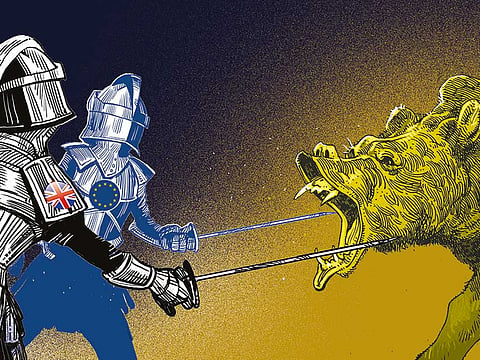

On Russia, Europe closes ranks with the UK

As Britain remains bent on leaving the EU, it must realise that its true friends and staunch allies are in continent

Of all the vacuous slogans generated by the entire Brexit campaign and process, “Global Britain” is the most vacuous of all. Not before time, the phrase is being called out for what it really is. Last week the Commons foreign affairs select committee dismissed it as meaningless, the former head of the Foreign Office trashed it as “mushy thinking”, while the Economist scorned it as “globaloney”.

Yet still Theresa May presses on with using it. Global Britain is a slogan masquerading as a policy. Predictably, it therefore appeals to Boris Johnson. The foreign secretary has said it shows that Britain is not “some bit-part or spear carrier on the world stage”. In fact, as the Economist’s columnist rightly pointed out, it is three foolish ideas rolled into one: complacent grandiloquence about Britain’s standing, dismissive perversity towards Europe, and post-imperial fantasy about the English-speaking “Anglosphere”.

The Salisbury attack ought to be a national wake-up call about such muddled, lazy thinking. Whether it was carefully timed is unclear. But it was certainly much more than an attempted spy-on-spy murder attempt. It was a state-on-state declaration. The attack on the Skripals, coming on top of several other mysterious deaths of high-profile Russians, proclaimed to the world that Britain is a weak country, and getting weaker.

At the start of this year a senior British diplomat told me that, post-Brexit, the big message he got when he talked to opposite numbers was that the world sees Britain leaving the EU as a step away from reality. It sends them, he said, an unmistakable signal that Britain does not matter as much any more and that it is turning inward. And this has happened just at a time when the US is ruled by a compulsive disrupter and China by a strategic autocrat.

Yet behind the rhetorical flatulence, something interesting may nevertheless be happening. That something is the very opposite of what the Global Britain fantasists either want or intend. For at precisely the time when Britain still remains bent on leaving the EU, many of the UK’s policymakers are cleaving ever more determinedly to Europe in other ways.

The most striking of these moves is in the UK defence world, and it has permission from the very top. May often says that Britain wants a “deep and special security” relationship with Europe after leaving the EU. The words often seem ridiculous in a Brexit context. But in defence, they describe something increasingly real. On most of the issues facing European nations, the UK is now closer to its main European allies than it is to the US.

This week, in a rare on-the-record speech, the permanent secretary for the MoD, Stephen Lovegrove, put a name to it. He called it a policy of “leaning to Europe”. Lovegrove’s speech to King’s College London’s Strand Group was very clear. It was an “absolute priority” to be a partner in continuing European defence projects. In the task of defending the nation and in defence planning, “We’re not going to do ourselves any favours if we pretend we can row our own boat.” Britain’s allies saw it the same way. “You can’t optimise European defence without Britain,” he added.

In defence terms, this is not really new thinking. Along with France, Britain has long been the highest spending and best equipped of the western European Nato states. What makes it new, though, is the context. In the age of Trump and Brexit, these assertions that Britain intends to continue to treat collective European security as an absolute priority inevitably seem freshly freighted. They have nothing to do with the Global Britain claptrap. They have everything to do with a hard-headed recognition that, when the chips are down — as they are in the Skripal case, for instance — Britain is a European nation and a European partner. It would be extremely surprising if they were not reflected in the outcome of the current strategic defence and security review.

The Skripal case has underlined this in many ways. What did May do after the attack? She didn’t pretend to be leading a superpower. She didn’t threaten war. She didn’t adopt the inane approach of blowing raspberries at Russia, as Johnson and the new and unimposing defence secretary, Gavin Williamson, did. Instead she stayed on the moral high ground. She turned to Britain’s allies on the basis of their shared values.

Understanding alliances is just as important for political leaders as understanding threats. Britain’s allies are in Nato and, for another 12 months, the EU. Both have responded decisively to UK calls for solidarity in the last week, and for good reason. Any state that decides it can murder people in our country will ultimately be prevented from doing so only by the opposition of a collective security alliance that efficiently penalises those who ignore international rules. That is why these alliances exist, and it is why Britain should continue to be part of both of them, especially now.

— Martin Kettle is noted columnist and one of Britain’s foremost political commentators.