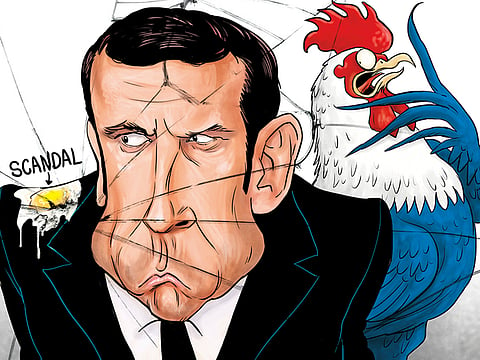

Macron thinks he’s untouchable, but the Benalla scandal could undo him

Cracks are appearing in the French president’s picture-perfect PR — and they come from within his own circle

It was just two weeks ago that French President Emmanuel Macron was on top of the world. At the World Cup final in Russia, he was photographed raising a victorious fist to celebrate France’s win. The snap quickly went viral, as the president fired up tweets to cheer the champions. Less than a week later, his Twitter feed had gone silent as his presidency endured its first major crisis.

No one in France took note of an article in the Times, published on July 26, about the Macrons’ €62,000 (Dh266,988) annual hairdressing bill. While previous stories on how Macron spent €26,000 on makeup in three months, and how the Macrons ordered €500,000-worth of plates for the Elysee palace, have been used to criticise the presidential couple’s expensive lifestyle, this one made no splash. Indeed, Macron, sometimes dubbed “president of the rich” and compared to the “Sun King”, was already engulfed in a much worse PR scandal: His aide and bodyguard, Alexandre Benalla, was alleged by Le Monde to have impersonated a police officer and beaten up protesters at a May Day march.

The problem with what quickly became l’affaire Benalla wasn’t just that the Elysee knew about the aide’s violent acts and failed to take proper legal action (Benalla was suspended without pay for two weeks, but his case was not taken to court, and it was later revealed that he did get paid during his time off). It was also that Macron and the Elysee remained silent on the whole affair, taking more than 36 hours to fire Benalla, before speaking out only to downplay the case’s importance, with an aplomb bordering on insolence.

For days, Macron avoided journalists, only declaring cryptically: “The republic is unalterable.” Six days after the scandal had broken, he spoke for the first time, at a private event with his party La Republique en Marche in Paris, where he appeared to make amends: “I am the only person at fault,” he said. Yet, he then lashed out at the press, which he said “is not looking for truth any more” and “wants to be a judicial power”, and criticised MPs who had called for an investigation into the case. He even boasted, shamelessly: “If they want a person at fault, he stands before you. They can come and get me. I answer to the French people.”

Over the next days, he called the affair “a storm in a teacup” and was filmed laughing the whole thing off: “We’re happy. Everything is fine!” (Everything was not fine, and the French media continued to break details of Benalla’s extensive access to the Elysee, the French parliament and the police, while the government’s statements contradicted themselves.)

‘Sun King 2.0’

There are two faces to Macron: The PR president who smiles on selfies and gives never-ending speeches, and the leader, a workaholic control freak who surrounds himself with a few trustworthy aides. Macron’s Elysee runs on a system of concentric circles of which he is the absolute centre. The “Sun King 2.0” (Bloomberg’s joke, not mine) has created his own court.

Benalla was in Macron’s inner circle. Questioned by the French parliament during the ongoing investigation into what the Elysee knew about Benalla’s actions, the Paris police commissioner described the case as a series of “unacceptable, reprehensible downward slides, against a backdrop of unhealthy cronyism”. Interviewed by Le Monde, Benalla himself said: “Everything at the Elysee is based on what can be exchanged in terms of proximity with the president. Is he smiling at you? Is he calling you by your first name? It’s a court phenomenon.”

Royal comparisons have gone much further. In May, the Elysee spokesman Bruno-Roger Petit said: “For Macron, the touch is fundamental. It is performative: ‘The king touches you, God heals you’. It is a form of transcendence.” The “king” Macron is known for holding exclusive dinners on Monday nights, with a dozen selected guests. The rule: Those who speak about it will not be invited again. After Macron dared his critics to “come and get [him]”, the hashtag #AllonschercherMacron, or “let’s go get Macron”, started trending and people joked that he had probably fled to Varenne, where then king Louis XVI was caught in 1791 before he could escape the French Revolution.

Ariane Chemin, the journalist who first broke the Benalla story, explains that: “Macron and his close circle conquered the Elysee as a commando unit. But they don’t understand that they cannot rule as a commando unit.” As a result, Macron’s vision of the balance of powers is very restrictive. Le Monde has written about the president’s “distrust of counter powers” and journalists have expressed concerns over the “rupture” that it marks.

Cracks are appearing in the king’s picture-perfect PR. They come from within his own circle, as Benalla has said that he is “not against” being questioned by parliament; and from the opposition, as MPs from the right-wing Republicains and several leftwing parties have filed two separate votes of no confidence. They have, after all, dared to “come and get him”.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Pauline Bock is a French journalist based in Britain. She writes for the New Statesman.