Lessons from the Third Arab–Israeli conflict

The 1967 war gave rise to Israel as a new Sparta and the emergence of Palestinian nationalism as a force to contend with

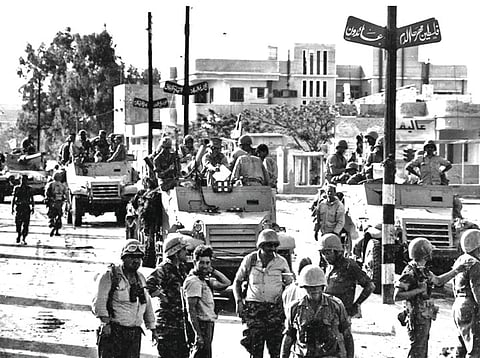

Fifty years ago, on June 5, 1967, the Israeli Air Force launched a devastating attack on both the Egyptian and Syrian Air Forces while they were still on the ground. Without air cover, the armies of Egypt and Syria were vulnerable to attack. It was the worst defeat in modern Egyptian history. The Israelis sought to justify the assault before international public opinion as an act of self-defence by invoking international law. The Egyptians and Syrians naturally interpreted it as an act of aggression.

The tension that had preceded the strike was palpable. The drums of war were being beaten loud. The assault was masterfully planned, carefully executed and it swiftly achieved its goals: Conquest of the Sinai from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan. Thus began a war that was to last a mere six days, but with serious ramifications at both the regional and global levels.

Although the 1967 war was officially condemned by the international community as an act of aggression, the feat of the Israeli Air Force was praised. The coordination, skill and discipline necessary for the successful execution of the Israeli war plans, left the objective observer in awe. A new Sparta had emerged.

In Egypt, the intelligentsia and the elites woke up from their torpor and demanded accountability for the brutality of the defeat. They argued that had Egypt not been ridden with corruption, nepotism and sloganeerism, while the enemy was preparing for war, it could have withstood the shock.

The military and political establishments, forever intertwined, were astonished by the speed with which a whole system, with its socio-political, and cultural institutions, could collapse and disappear overnight.

In Tel Aviv, people celebrated; in Cairo people mourned and a sombre mood reigned. The streets were full. The crowd wailed. The agony of defeat profound.

A few days after the debacle, Egypt’s then president Jamal Abdul Nasser announced on national television that he accepted responsibility for the bitter and profound loss and offered his resignation effective immediately. Hundreds of thousands of Egyptians poured onto the streets to insist Nasser to stay on. He accepted the will of the people and remained in office. But he was a broken man. However, he was able to challenge Israeli air superiority by relying on political and military aid from Moscow. With the use of Soviet made surface-to-air Sam 20 missiles against Israeli fighter jets, he waged a war of attrition that was meant to wear down Israel by means of a long engagement.

The Rogers Plan

Nonetheless, it was humiliating for the Egyptian army to accept the condition that the missiles be operated by Russian experts. Nasser accepted a peace plan presented by William Rogers, former United States secretary of state Henry Kissinger’s arch-rival in the administration of former US president Richard Nixon. The Rogers Plan provided for:

1. An Israeli withdrawal from Egyptian territory occupied in the 1967 war.

2. A binding commitment by Israel and Egypt to achieve peace.

3. Negotiations between Israel and Egypt regarding areas to be demilitarised.

4. Free passage through the Gulf of Aqaba.

5. Security measures for Gaza.

The plan was rejected by Golda Meir, the then Israeli Prime Minister. She was not interested in giving legitimacy to Nasser’s regime or giving up the territories occupied in the 1967 war. Nor was she ready to give in to the combined pressure of the Americans and Russians, who, in 1956, had forced Israel to withdraw their troops from the Sinai. Nasser had been able to transform the military retreat from the Sinai into a political gain and thus became a hero — not just for Egyptians but for the Arab world.

Unfortunately, with Nasser’s sudden death due to a heart attack, Arab nationalism also died, along with its rallying cry to oppose imperialism and colonialism. Israel had just inflicted a humiliating defeat in the Sinai desert, the West Bank and the Golan Heights. It was at this time that the role of Israel as a strategic US ally in the Middle East came to the fore.

The 1967 war gave rise to Israel as a new Sparta and the emergence of Palestinian nationalism as a force to contend with. The absence of a peace process eventually led to interactions between these forces and within six years they had coalesced into yet another war.

Adel Safty is distinguished visiting professor and special adviser to the rector at the Siberian Academy of Public Administration, Russia. His book, Might Over Right, is endorsed by Noam Chomsky and published in England by Garnet, 2009.