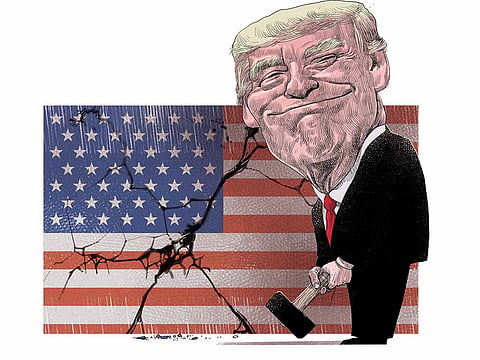

Is ‘Brand America’ under threat?

The incoming administration threatens to potentially damage the standing of the US worldwide

As President-elect Donald Trump continues making his picks of US officials, including the controversial announcement on Friday of Ambassador to Israel David Friedman, his upset poll victory is still sending shock waves around the world. The choice of right-wing lawyer Friedman, for instance, has already been heavily criticised by many Palestinians given his reported opposition to a two-state solution to the conflict, and support for Israeli annexation of the West Bank.

The continued shock at Trump’s election, and some of his early decisions and appointments, threatens to potentially damage the reputation of the United States (so-called ‘Brand America’) internationally. Indeed, Shashi Tharoor, former UN under-secretary general and a current Indian MP, has already asserted that the billionaire businessman’s presidency could mean “the end of US soft power” by exposing “tendencies the world never used to associate with the US: xenophobia, misogyny, pessimism and selfishness”.

Brand America is especially likely to take a battering if Trump continues with the undiplomatic pronouncements he regularly espoused during the campaign. Examples here include his assertions in April that Washington should withdraw US troops from South Korea and Japan and allow those countries, and potentially others, including Saudi Arabia, to develop nuclear arsenals.

While these ideas enjoy some support in the United States and internationally too, they fly in the face of US foreign policy over decades which has largely been focused on preventing nuclear weapon proliferation. So significant was the level of diplomatic concern in Japan, for instance, that both the prime minister and foreign minister responded forcefully, with the latter asserting that “it is impossible that Japan will arm itself with nuclear weapons”.

These controversies are only one example of a string of foreign policy indelicacies. Other instances of diplomatic angst he has caused relates to his plans for building a border wall with Mexico (which he claims the Mexican government will pay for); and a proposed ban on all Muslims entering the United States (a commitment which he has since backtracked from).

Much will now depend on whether Trump continues to adopt the occasionally more conciliatory language that he has adopted since election-day, or whether the wild rhetoric and policy ideas of the campaign return. If so, there is likely to be a spike again in anti-US sentiment in at least some key countries for the first time since George W. Bush’s presidency.

And this could undercut much of the work that President Barack Obama has undertaken to turn around the climate of perception about the country in the last eight years. Coming into office in 2009, Obama confronted a situation in which anti-US sentiment was at its highest levels since at least the Vietnam War. The key factor driving this was the international unpopularity of the Bush administration’s foreign, security and military policies in the so-called ‘war on terror’.

The ‘Obama effect’

The Obama team has done much to reverse these public opinion patterns. And according to one research study that uses the same tools that consultants use to value corporate brands, the “Obama effect” was estimated to have raised the value of ‘Brand America’ by $2.1 trillion (Dh7.71 trillion) in the first year of his presidency alone.

This reflected the substantial increase in foreigners regarding the US as the most admired country in the world again following the Bush presidency. And this turnaround in fortunes was not only been welcomed in Washington but also in Corporate America following concerns during the Bush years that US-headquartered multinationals were becoming a focus for commercial backlash from anti-Americanism.

However, despite these successes, Obama’s progress has been uneven in the last eight years. Perhaps the biggest failure of Obama’s global public diplomacy has been toward what he has called the Islamic world. Despite the early promise of his Cairo speech in his first term in which he sought to reset US relations with Muslim-majority countries, there remain pockets of very high anti-Americanism in several key states, including Pakistan and Egypt, which the president has failed to substantially address.

While Trump was criticised during the campaign by audiences across much of the globe, it is in the so-called Islamic world where the risks to Brand America are potentially highest. For instance, his previous plans to “shut down” immigration from all Muslims have been called “unacceptable... an insult to our religion” in the UAE, while Egypt’s top religious authority decried his “hostile view of Islam and Muslims”.

US public diplomacy problems, however, are not just restricted to Muslim-majority countries. Many internationally, for instance, have been disappointed by Obama’s failure to close Guantanamo Bay, and there is significant foreign unease about increased US use of drone strikes during his presidency.

It is in this context that foreigners are viewing Trump’s elevation to the presidency. And it appears possible that global opinion could possibly be even more hostile to him than Bush, highlighting the downside risks for Brand America.

The risk is heightened by the fact that Clinton was much more favoured than Trump by foreign audiences to be the next US president, partly because she was perceived as the ‘continuity candidate’ for the Obama administration. She was, for instance, the stand-out winner, in a poll of nearly 50,000 people in 45 countries, covering 75 per cent of the world, by WIN/ Gallup International Association. The survey found Clinton was favoured (often strongly) over Trump in all but one country, Russia.

These results were very similar to those by Handelsblatt that were taken with some 20,000 people in the G20 countries. Once again, Russia was the only state where Trump bested Clinton.

Taken overall, Trump has potential to be one of the least popular ever US president overseas. While Brand America has rebounded under Obama, there are now significant downside risks for the US reputation overseas should the new president-elect return to the sometimes wild rhetoric and controversial policy positions of his campaign.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS (the Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy) at the London School of Economics.