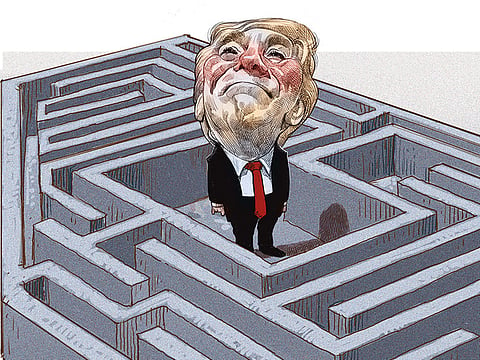

How Washington got outplayed on North Korea

Trump’s inconsistency weakened America’s hand, while others skilfully manoeuvred to advance their agendas

The May 24 letter from US President Donald Trump to Kim Jong-un, apparently ending their nuclear negotiation bromance, should come as no surprise. But by once again catching American allies off guard and publicly antagonising North Korea, the administration has further undermined its own leverage.

Over the past year, the president has repeatedly underestimated the importance of making real trade-offs in diplomacy. These choices appear to be anathema to his “go big or go home” style of deal-making. The Trump administration has been eager to jettison the “weak,” “terrible” deals negotiated by previous presidents — including the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Paris climate agreement, and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran. With North Korea, he was seeking something bigger and better, “a very special moment for World Peace.”

Instead, the United States may now walk away with nothing. While it’s true that deals like the Iran nuclear agreement had inherent shortcomings, they also effectively advanced America’s national security. In fact, their limitations reflect a hard-nosed assessment of the risk of the alternatives, the broader geo-strategic interests in play and the constraints on America’s leverage. In diplomacy, every deal is an imperfect deal. The question is, how imperfect? And at what cost?

Unless you can produce a better alternative, tossing out a less-than-perfect agreement that does advance some concrete goals is an exercise in peril. “Repeal” is almost always simpler than “replace.”

There may still be time to avoid the all-or-nothing trap with North Korea. While it will not be easy to overcome the fallout of provoking a thin-skinned dictator, the United States might now have a chance to focus on a more credible strategy: a deal that constrains, even if it does not immediately eliminate, North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes without offering unacceptable concessions in return. Whether such a deal is possible depends on Trump’s ability to embrace the art of the imperfect deal.

Developing a stronger negotiating strategy requires acknowledging the obvious: The United States has less leverage than it thinks in this negotiation. Over the last few months, the Trump administration has repeatedly insisted that near-term denuclearisation is achievable. This assessment flies in the face of North Korea’s pointed recent statements and long history to the contrary, and it contradicts a new Pentagon report that suggests Kim views nuclear weapons as essential. No amount of wishful thinking, or even the possibility of reduced American sanctions, will change this reality.

The Trump administration will also need to address the divisions among its partners in the region, where Trump’s inconsistency has weakened his hand in negotiations and allowed our Asian partners to more skilfully manoeuvre towards their own goals.

Leveraging the art of flattery

President Moon Jae-in of South Korea has repeatedly leveraged the art of flattery with Trump to ensure that South Korea’s vision of a sweeping peace deal remained on the table. Moon is likely to keep pursuing some kind of diplomatic play with or without Trump’s involvement.

China, which will never share in America’s urgency about denuclearisation, continually dangled the prospect of deeper cooperation on North Korea to head off far more worrisome actions by the United States on trade policy — all while simultaneously shoring up relations with Pyongyang. President Xi Jinping may not want a war, or a nuclear-armed ally on his border, but he can live with most of the undesirable possibilities in between. And he has now gotten the United States to put the trade war “on hold,” at least for now.

Not to be outdone, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan has visited Trump several times to ensure that the United States does not cut a narrow deal that puts Japan’s security at risk. These divergent interests won’t be readily reconciled. Instead of ignoring these differences, the administration needs to find some common ground for a more unified negotiation. Otherwise, the other power centres in Asia may pursue side deals with North Korea that will be even worse for the United States.

Finally, a more viable strategy requires a clearer analysis of how important North Korea really is to American interests, and what the United States is willing to put on the table. Is the top priority dealing with the threat of intercontinental ballistic missiles, or reducing North Korea’s nuclear stockpile? Where is the United States willing to accept calculated risks? The Trump administration must answer these questions to ensure that the United States doesn’t give up too much — like suddenly reducing its military presence in Asia or weakening its alliances — without getting anything substantive in return from North Korea.

Continuing with Trump’s all-or-nothing tactics increases the risk of making strategic errors elsewhere. The longer the United States remains obsessed with North Korea, the less prepared it will be to address more important challenges, like China’s escalating assertiveness in Taiwan and the South China Sea. And the United States could miss the chance to capitalise on opportunities as they arise, such as this month’s historic election in Malaysia — a stunning triumph of democracy over corruption that registered as little more than a blip on America’s radar.

If the past six weeks of diplomatic speed-dating over North Korea have made one thing clear, it’s that all the other people at this dance have a clear strategy and are playing their limited hands to full effect. The Trump administration, meanwhile, has attitude, swagger, and now a break-up letter for the ages. What it doesn’t yet have is a viable strategy. Hopefully, Trump will seize this chance to find one.

— New York Times News Service

Lindsey Ford is the director of political-security affairs for the Asia Society Policy Institute in Washington.