The European Union (EU) has faced two major crises over the past six months — one involving the euro, the other involving refugees. By coincidence, the same two countries are at the centre of both problems — Greece and Germany. Last summer, Germany almost forced Greece out of the euro, rather than agree to the EU lending further billions to the Greek government. Now, Germany is reeling under the impact of the arrival of more than one million would-be refugees, most of whom have entered the EU through Greece.

It is time to think creatively about how these two problems could be linked into a diplomatic package that helps to fix them both. The broad outlines of the deal would be simple. Greece agrees to seal its northern border with EU help, stopping the flow of migrants into northern Europe. In return, Germany agrees to a massive writedown of Greek debt, as well as immediate financial aid to cope with the current crisis. Refugees arriving in Greece are then housed in EU-run camps on Greek islands in the expectation that they will return to Syria (or wherever else they are fleeing) once peace is restored.

This plan sounds far-fetched. But parts of it could already be emerging, by trial and error. EU officials are known to be considering “ring-fencing” Greece by blocking the border between Greece and Macedonia, which is the main route north. According to a report, this plan is “believed to have support in Berlin”. Action could come quite soon. Last week, Mark Rutte, the Dutch Prime Minister, said that the EU has to get control of the refugee problem “in the next six to eight weeks”, adding: “We can’t cope with the numbers any longer”.

On first consideration, any notion of bottling up refugees in Greece sounds chilling. Managed badly, that could strand hundreds of thousands of desperate migrants in a country of 11 million people, which is struggling with 25 per cent unemployment and a national debt approaching 180 per of gross domestic product.

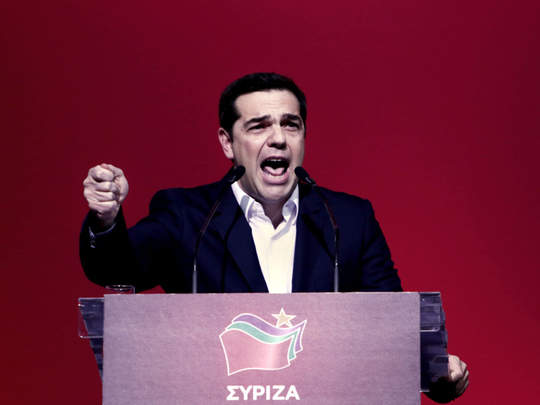

But Greece’s crippling debts could actually be the key to the problem. The government of Alexis Tsipras, the Prime Minister, has repeatedly insisted that Greece’s debts are crushing the economy. Germany, which is the largest single lender to Greece, has repeatedly insisted that German loans to Athens must eventually be repaid. But the refugee crisis has given German taxpayers a more urgent problem to think about than the relatively abstract question of when Greece will pay back its debts.

If the Greeks were seen to be doing the Germans a massive favour by stemming the flow of refugees, it would become much easier for Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor, to make the case for debt relief for Greece to her voters. And once the Germans moved, the rest of Greece’s creditors could be expected to fall in line. The deal could also be very attractive for Greece. It would get permanent relief from unpayable debts, in return for a temporary role as the EU’s main reception centre for refugees. The EU could also take on the burden of funding and running the refugee centres on Greek soil, which could provide protection and education for children and an opportunity to work for adults.

Some will object that it would be immoral or illegal for Europe to change the current system of asylum. But that system is on the point of breakdown, anyway, and is fuelling the rise of political extremists inside the EU. Most Europeans feel compassion for refugees in fear of their lives but are also worried about uncontrolled mass immigration from the Middle East.

So it is critical to break the connection between the offer of temporary protection from warfare and the offer of permanent immigration into the EU. Once that connection is severed, European public opinion will be reassured. And while people in danger would continue to be protected inside Europe, closing the route to Germany would weaken the pull-factor for economic migrants.

A model that Europeans could think about are the camps set up for millions of displaced people in Europe after the Second World War. These provided shelter and helped families reunite. Many displaced people were eventually resettled in third countries because European borders had shifted. But the preferred option was always that refugees would return to their home countries.

The situation in the modern Middle East — dire as it is — is actually less disordered than that of post-war Europe, which makes it more realistic to expect that Syrians, Iraqis and others could eventually return home. The task of rebuilding Syria, after the war, will also be immensely easier if the Syrian middle-class has not, in the meantime, dissolved into the EU. Indeed the eventual repatriation of Syrian refugees would be crucial to giving the country a future.

Of course there is a danger that the war will drag on and on and that “temporary” refugee centres will become permanent — as has happened with Palestinian refugee camps. But if, in a couple of years’ time, there is still little prospect of Syrians returning home, the status of those living in EU refugee camps could be rethought. At least that reassessment would be carried out in an orderly and thoughtful way, rather than in the current atmosphere of chaos.

I am sure that a serious examination of a debt-for-refugees deal between Greece and Germany would throw up all sorts of practical, moral and legal problems. But I have yet to hear a better idea.

— Financial Times