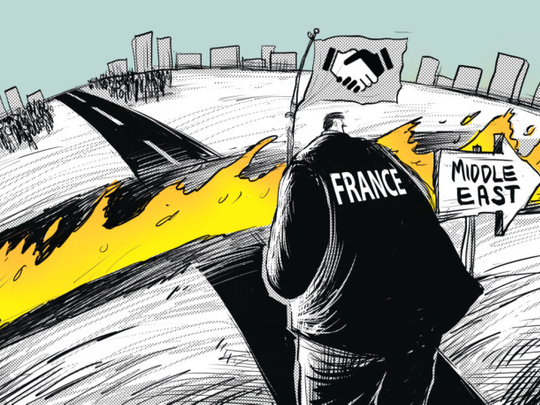

Surprisingly, outlines of the future French diplomacy, especially in the Middle East, seem to interest very few in France, whether voters or presidential candidates. The only notable exception being former prime minister Francois Fillon, who is the only candidate running for president with a statesman profile.

According to recent studies, matters of interest to the French (in decreasing order) are terrorism, immigration, social protection, unemployment, environment and public debt. One could think that terrorism and immigration are international issues, but the French think otherwise. Many in France are scrutinising these events through an ethno-centric approach, full of irrational fears towards globalisation and the European Union (EU). Populist themes developed by some candidates have started to pay off and don’t seem to hurt the socialist candidate Emmanuel Macron, a fervent supporter of globalisation. However, many voters are yet to discover the true nature of Macron’s policies. Such a picture confirms that the fringe of neo-conservative French diplomats who have been on the forefront in Libya or Syria, will pursue their activities, unless they are stopped by a new political force with someone like Fillon at the helm.

Two situations at least would indeed require a shift in policy. United States President Donald Trump’s recent declarations about the Israel-Palestine conflict illustrates one of them. Nobody really paid attention to the 75-member Paris conference that took place on January 15 since none of the main protagonists was attending. A few optimistic minds paid greater value to the United Nations resolution 2334, adopted a month earlier, without the US affixing its veto. Reminding the international community about the condemnation of illegal Israeli colonisation of Occupied Territories didn’t amount to much. Such resolutions nevertheless have legitimacy for countries that value international law. This has not been the case for Israel since 1967.

The coming of Trump has ignited a series of questions: Be it his inner circle, his nominee as the ambassador to Israel, or his declarations about moving the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to occupied Jerusalem — his choices were contentious even though Trump is accustomed to change his mind overnight. His recent encounter with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu makes him move further ahead.

Giving-up the two-state solution is indeed a step towards the end of the Jewish state. It appears that the two-state solution has now become that kind of mirage that makes ‘experts’ happy, but to which a minimum degree of support is missing. The forthcoming annexation of Ma’ale Adumim and the recently passed bill over legalisation of 50 illegal colonies (800 hectares of land) are facts that render irreversible any future Palestinian state. Trump knows it, but his advice to Netanyahu, “to go slow on colonisation”, strangely echoes former Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon saying “it is not necessary to call the press while colonising...”

Regaining control

France has been supporting the two-state solution for years. The question arises whether any candidate will be courageous enough to tell Israel that it should respect international law. In Europe, this may well be dubbed being ‘anti-Semitic’? Trump still has a lot of time to change his mind on a 70-year old conflict, but shouldn’t French diplomacy raise the tone and finally officially recognise the Palestinian state?

In Syria, the situation is relatively easier to settle, since it is mainly in the hand of one country, Russia. The facts on the ground are more or less accepted by everyone: The Syrian National Army has regained control of a large part of territory — but it is unable to stand alone. There is a complicated presence of rebels in the entire spectrum of Syrian society — from secular revolutionaries to deeply religious people not far from Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant); there are ‘palace’ combatants in the middle; Kurdish fighters looking for independence that nobody wants to give them; blood-thirsty fighters, more or less manipulated and financed by external forces; a remaining dictatorship, which believes it can recover control over the whole country, and which remains characterised by corruption and the rampant use of torture.

Through promoting a “no-Bashar [Al Assad] no-Daesh” policy, France has excluded itself from any resolution of the conflict. Fillon, who doesn’t like Syrian President Bashar Al Assad but finds it difficult to fight Daesh without him, advocates pragmatism. French diplomats in charge, on the other hand, are now promoting a kind of negotiation between the parties — still insisting Al Assad has no future and meanwhile, making sure he will not consolidate his position through the reconstruction of the country, as the EU proposes. A document released by the daily Le Figaro shows that France thinks of establishing ‘exclusive zones’ to be held by rebels that would become ‘autonomous’ over time.

Once again, such reasoning confirms how French diplomacy has difficulties appraising the situation in Syria. Many cards are in Turkish and Iranian hands, but the levers lie with the Russians. It is incumbent upon the new French President to take up the issue of Syria with his Russian counterpart. Fortunately, it is precisely part of Fillon’s programme.

Luc Debieuvre is a French essayist and a lecturer at IRIS (Institut de Relations Internationales et Strategiques) and the “FACO” Law University of Paris.