Delhi defeat should be a clear message to Modi

He needs to live up to his pledges of radical changes to India’s economy

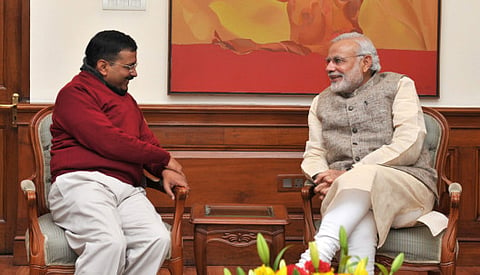

In the Delhi elections, voters left no doubt about whom they prefer to govern India’s capital region. Official results released on Tuesday showed that the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), led by populist anti-corruption campaigner Arvind Kejriwal, had swept 67 of the 70 seats in the legislature — a record — and cornered more than 50 per cent of the vote, a rarity in India’s multi-party, first-past-the-post system. Voters were clearly sending a message. The question is to whom?

Strategists from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which had swept to power nationally in its own landslide last May, have been quick to insist that the debacle does not represent a referendum on the prime minister’s nine months in power. And it is true the election was dominated by issues and personalities specific to Delhi. The BJP’s local leadership has traditionally been weak; it has failed to win the legislature since 1998.

Yet, Modi is unquestionably the face of the party and has been only too happy to take credit for its recent slew of victories in other state elections. He handpicked the BJP’s candidate for Delhi chief minister — Kiran Bedi, another well-known campaigner against corruption — and repeatedly asserted that the capital’s voters reflected the national mood. The BJP’s campaign slogan exhorted voters to “walk with Modi”.

In the last local elections in December 2013, the BJP had won 31 seats in the legislature. In May 2014, Modi helped the party sweep all seven of Delhi’s parliamentary seats. The scale of the BJP’s reversal now is stunning: Voters have unquestionably grown impatient waiting for the “achche din” (“good days”) that Modi had promised them.

The prime minister may regret having raised expectations so high with his candidacy. He promised new jobs, to revive growth, lower inflation and end corruption and cronyism. His record on all fronts has been patchy. The economy, despite buoyant new gross domestic product growth figures — ginned up by a revised methodology — is only beginning to sputter back to life. The plunge in global oil and commodity prices has caused inflation to ease and put the economy on a sounder footing. But in the absence of dramatic reforms, investment — particularly private investment, which is key to sparking growth — has not been forthcoming.

Meanwhile, the public investment needed to kickstart infrastructure projects has been constrained by India’s large fiscal deficit. Even the limited reform measures Modi has introduced — on land laws and increased foreign investment in the insurance sector — have been blocked in the Upper House of parliament, which the BJP does not control. Modi’s strategy of ramming through reforms using executive ordinances has created doubts among investors about how lasting the measures will be.

Modi’s personal record on corruption is impeccable and no scandal has rocked his government so far. Still, the prime minister has not been able to shake off perceptions of cronyism. A proposed loan of $1 billion (Dh3.67 billion) from the government-owned State Bank of India to Gautam Adani, a prominent industrialist from Modi’s home state of Gujarat, created a perception problem, even if it was aboveboard. Modi’s aloofness from the mainstream media has been puzzling. It certainly has not helped his cause.

In the end, voters judge politicians on the promises they make. Among other things, Modi vowed to bring back the illicit wealth accumulated by wealthy Indians in offshore bank accounts and to deposit Rs1.5 million (Dh88,348) into the bank account of each Indian family using the proceeds. But during the Delhi campaign, BJP president Amit Shah claimed that it was a rhetorical pledge. For voters, it was a broken promise.

The lessons for Modi should be obvious: He needs to live up to his pledges of radical changes to India’s economy and investment climate, and fast. The first test will come at the end of this month when his government presents its first full budget. If he does not introduce bold reforms then, his political capital will likely begin to seep away.

There is a lesson for the popular Kejriwal as well. He has promised Delhiites many things, including subsidised power and water. As chief minister, he will have a very hard time fulfilling those pledges without busting the budget. And as Modi has discovered, much to his chagrin, Indian voters are unlikely to be forgiving.

— Washington Post

Dhiraj Nayyar is a journalist in New Delhi.