When the economist Gunnar Myrdal was researching his book Asian Drama, his classic investigation into Asian poverty, he found that one subject was “almost taboo” among scholars and planners.

No matter which learned institutions they were from, none wanted to talk about corruption. Many other, often poorer, people did. As Myrdal pointed out in 1968, authoritarian regimes in the region often came to power on the promise that rampant bribery and nepotism would be eradicated, either by the Communists (for whom corruption was an inevitable by-product of capitalism) or by the army (which saw it as a result of poor social discipline), depending on who was leading the change.

So why were academics and well-meaning international agencies so silent? Myrdal concluded that they were too embarrassed to ask about it. And when Myrdal asked them why they hadn’t asked, they were liable, if they were Asian, to say that every country in the world was corrupt in one way or another; or, if they were from the west, that corruption was “natural” in countries such as India and Pakistan because of attitudes that survived from colonial and even pre-colonial times. Both statements may have been true. Neither was a good excuse for not finding out more — where and among whom corruption prevailed, how it worked, who profited and who lost from it. In the early post-colonial decades, it was an inconvenient truth rarely mentioned in polite international conversation.

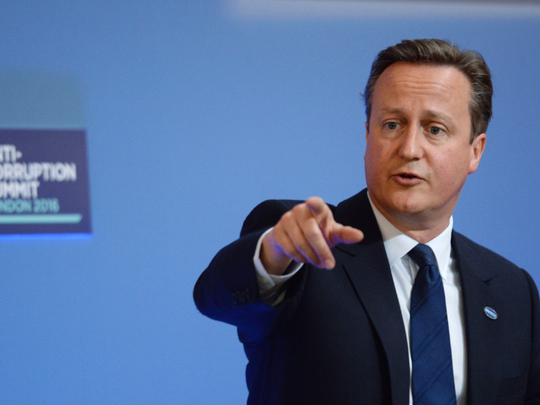

Things are different now. Corruption has been out of the closet for years and last week reached new heights of publicity, at least in the UK, with British Prime Minister David Cameron’s unguarded remarks to the Queen about the “fantastically corrupt” countries attending his anti-corruption summit in London.

In more considered statements at the conference itself, Cameron recognised corruption “as the cancer at the heart” of many global problems; a crime that cost the world economy billions of pounds every year, eroded human values and deepened the poverty of the already poor by diverting into private hands money that should have been spent on schools, hospitals and thousands of other civic projects. And it didn’t just happen elsewhere. “Make no mistake, corruption affects us all, Britain included,” Cameron said. Tax evasion, money laundering via tax havens, the Westminster expenses scandal: “We have our own problems and we are very much still dealing with them.”

According to its published aims, the summit is intended to encourage governments to take practical steps to “expose corruption so there is nowhere to hide” and “drive out the culture of corruption wherever it exists”. These are noble ambitions, but some scepticism would be wise.

Menace keeps spreading

Well-attended international anti-corruption conferences have occurred at fine locations every two years since 1983; the UN convention against corruption, signed by 140 nations, has been in place since 2003 and contains dozens of legally binding articles outlawing embezzlement, money laundering and bribery; an International Anti-Corruption Day is observed annually on December 9 (though it would be interesting to know how and by whom).

And yet it has gone on growing, in great underground rivers of money with their headwaters in the collapse of the Soviet Union and to a lesser extent the power of states nearly everywhere in the face of neoliberal economics, easy, instant communication, and the vanishing bonds of good citizenship.

As a word, it covers many different kinds of behaviour. An Indian railway ticket collector is corrupt when, in return for a few extra rupees, he finds you an overnight berth that, if the rules had been observed, would have gone to another traveller. But how does that relate to a British arms company winning a contract to supply guns to a foreign government after a few million in backhanders have been slipped to its minister of defence; or the villa in Hampstead purchased from funds illegally exported from Russia?

Are they merely small and large examples of the same crime? Is a state that turns a blind eye to the first more likely to permit the second and third? Is the same kind of personality involved? Can the culprit progress like an addict from the soft to the hard stuff, from ticket inspector to international arms dealer, in the course of his social fabric-rotting career?

In an essay for last week’s summit Francis Fukuyama wrote that, just as the 20th century was characterised by the ideological struggles between democracy, fascism and communism, corruption has become the defining issue of the present century. He, too, struggles to separate different kinds of corruption, but he provides a clue to the reasons for its recent growth: the modern state, “which seeks to promote public welfare and treats its citizens impersonally”, is a recent and inherently fragile phenomenon that runs counter to the human instinct to show favouritism towards family and friends. As the state gets weaker, the opportunities to break, elude and ignore its rules grow. Being a good person and obeying the state become different things, at least in the eyes of the individual. Corruption means breaking the rules devised for the public good for personal gain.

In India until 20 or 30 years ago it was easy in a village or small town to meet older residents who recalled a time when the district magistrate, the person who sat at the apex of the local administration, was British. Often he would be fondly remembered: “a fine gentleman — incorruptible”, people might say, contrasting him with a more recent state of affairs. Officials in the old Indian civil service observed strict rules — no gifts other than fruit and flowers — and retired on modest pensions to manageable houses in the home counties. The system they served, on the other hand, exploited and oppressed the people it ruled; “corrupt” might be the wrong word for it — the empire observed its own laws — but it certainly looted India’s revenues and raw materials.

Good exists in the unlikeliest places. In Katherine Boo’s brilliant study of a Mumbai slum, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, she describes how life there often depends on scams and deals that in one way or another cheat the state. “It is easy, from a safe distance, to overlook the fact that in under-cities governed by corruption, where exhausted people vie on scant terrain for very little, it is blisteringly hard to be good,” she writes. “The astonishment is that some people are good, and that many people try to be...”

For their sake, as well as the anti-corruption summit’s ambition to “drive out the culture of corruption wherever it exists”, strong, welfare-minded states governing cohesive societies seem more necessary than ever before. But the tide is against them.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Ian Jack writes a weekly column for the Guardian. He has covered South Asia as a foreign correspondent.