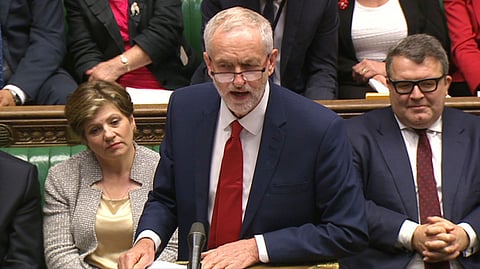

Corbyn’s uselessness has lost its charm, but he’s not Labour’s only problem

The party needs to move quickly to show that it stands for something as well as against everything

The ability to move fast in politics, as in real life, makes you seem flexible, agile and in control. Speed is decisive. All those who look on the current works of the Tory party are reeling with admiration at the blood-soaked tapestry and envy at the stitchup.

In a backroom deal, a small number of people decided who would be prime minister, but, look, here she is installed , and many are breathing a sigh of relief that someone is in charge. The man who was once the future is past; Theresa May has assembled her Cabinet and is signalling that there will be some significant changes in policy.

Meanwhile, Labour slowly bleeds out, unable to offer anything like a functional opposition, not able even to have a meeting that lasts less than several hours. It will lumber along wounded and snarling until a leadership election in September, apparently. Is this the end? The beginning of the end? Will there be a remission period? Possibly, but there is now something so profoundly sluggish in its gait that it is pitiful.

A modern party has to move fast and react quickly — socialism can’t be Skyped in — but in anxious times the Labour party needs to show it can jump. It hasn’t been able to for a long time and, by electing Jeremy Corbyn, it deliberately chose to reward endurance over agility. This crisis has been exacerbated by Corbyn, but it is not all about him. His “non-personality” or authenticity, or however it was spun, has resulted in one of the most bizarre personality cults, where this wiry man is carried along by a crush of police, media and fans between adoring rallies and hostile meetings with his own colleagues.

It is undeniable that the politics he represented were new and exciting to many. His very uselessness was seen at the early rallies, which I attended, as an indication of his untainted virtue. Lately, though, his uselessness has lost its charm — even for many who voted for him. What I hear people saying is that they still want someone to represent many of his positions — on Trident, on renationalisation, on inequality, for example — but they want someone with strategy and presence. They want someone and something that isn’t him, not because they are swivel-eyed Blairite triangulating traitors, but because they want something that works.

This is not all Corbyn’s fault: It is really about something much bigger. We are talking about at least three kinds of deep disenfranchisement here. First, the failure of the left to outline a plan or some policies that amount to more than vague “anti-austerity” talk still leaves many unmoved. If we are not talking about redistribution, what exactly are we offering? Slightly less jagged capitalism? Ed Miliband struggled with this — speaking of fairness or predators — but it was all a bit tentative. To bring in new voters, Labour has long needed to be for something as well against everything.

Meanwhile, May has already made some moves into that territory. The need for fiscal stimulus requires a rethink around debt and borrowing and the whole flimsy argument that underpinned austerity. Again, the inability of Labour to think on its feet in response to the fast-changing world is not because of one man’s indefatigability, but it is embodied in Corbyn’s long silences.

The second kind of disenfranchisement is the cultural gulf revealed by the Brexit vote. We can argue all we like about how and why people voted Leave, but the divides it points to are significant. This huge expression of loss is felt differently in different places, but it is felt every day.

Explaining to people that they have the “wrong” feelings is not an answer. The fear that those feelings of loss will cohere around the right is a clear and present danger.

Third, and just as disturbing, is the anti-democratic sentiment that Brexit has produced everywhere. Many thought the referendum should be annulled somehow. We now witness political elites keeping themselves in power by ignoring their own rules or making them so complicated that no one else understands them. The very relationship between “the people” and “the party” and “parliament” is being rewritten before our eyes. The attempt of the Corbyn crew to grow a social movement off the back of an elected leader rather than the other way round has produced this Podemos-lite aspect. The notion that it is still possible to function as a parliamentary party by bypassing the parliamentary bit is untenable. But it exists because there is now comfort in the knowledge that winning is for losers. This is extreme self-sabotage. It is sad that many young people do not know what winning might look like, but I would direct them to the all-round relief and happiness felt when Sadiq Khan became Mayor of London.

Apart from that victory, though, it is undeniable that Corbyn was a product of crisis not its sole cause. The fantasy that some special leader could change everything, that there really is “the one”, can no longer be maintained. This genuinely is about issues, not personality. As things get so very personal, it may be worth clinging on to that.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Suzanne Moore is an award-winning columnist for the Guardian.