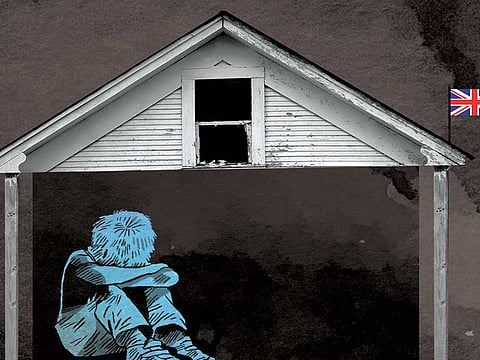

Child-abuse probe debacle shines harsh light on May

As home secretary, she fought hard to set up this review. Now, Britons will learn how much, as the prime minister, she strives to stop it unravelling

How must it feel, to have been let down as a child by those you were taught to trust, and then in adulthood to be let down all over again? It’s hard to imagine how painful the turmoil inside the British government’s child abuse inquiry must be for survivors of abuse. Already on its fourth chair, the inquiry has now suspended its counsel Ben Emmerson over unnamed allegations about his leadership — hours after reports that Emmerson was considering resigning because he felt the scope of the inquiry was impossibly wide. Now the inquiry’s second-most senior lawyer, Elizabeth Prochaska, has quit too.

To the understandable distress and anger of abuse survivors who have already suffered so much, the project seems to be slowly unravelling, raising awkward questions about whether its design was flawed from the start. And that is a question that leads past the current British Home Secretary, Amber Rudd, right up to her predecessor’s door in Downing Street. Theresa May, before she became Prime Minister, fought tooth and nail to set up that inquiry, overcoming resistance in some parts of No 10, and nobody doubts she did it for the best of reasons. She saw a group of vulnerable people grievously failed by the state and wanted to help them find some peace, to right historic wrongs. It would have been inhuman to feel otherwise. But the question of whether this huge, sprawling inquiry has bitten off more than it can chew can no longer be dodged. And while nobody wants to play politics with the lives of damaged people, the whole episode raises some awkward questions for the new prime minister.

Conservative party members gather in Birmingham today, for four days, for its annual party conference. This is May’s first chance to bask in the warmth of a grass-roots party grateful for the stability she has brought in recent months and reassured by her often-repeated commitment to Brexit, but it is also a chance to set out a programme to Britain. She has already coloured in the broad outlines.

The view from Downing Street is that former prime minister David Cameron didn’t just lose a vote on Europe, but a whole series of deeper arguments leading up to it — about globalisation and insecurity, elites and the powerless, the gap between booming London and the struggling provinces — for which both Remainers and Leavers in his Cabinet bear some responsibility. Whatever warm words May has for her predecessor, rebuke will be there in every reference from the platform to unfashionable concerns ignored, meritocracy stalled, voters overlooked. But if the bigger picture is very clear, the detail is missing, unless you count the gnomic “Brexit is Brexit” as an answer to the vast question of how on earth Britain can extricate itself from Europe without doing itself permanent harm. By refusing to provide what Downing Street calls a “running commentary” on Brexit negotiations, she is asking voters to take a leap of faith. Britons are simply being asked to believe that she’s got it all in hand, honest; that she is the sort of solidly reliable politician who can be trusted just to get on with things, behind closed doors.

And to be blunt, she could probably get away with that for some time yet, so long as people continue to regard her as a safe pair of hands. But were she to lose her reputation for brisk competence, then the public might very quickly start demanding proof that she does have a grand plan up her sleeve for dealing with Brexit.

By itself, the child abuse inquiry is not going to destroy a reputation gained over six gruelling years at the Home Office. But it is, if nothing else, a reminder that even the safest pair of hands can’t catch everything; that politics is a series of near-impossible judgement calls, and that even the best of politicians will eventually call one wrong. It is not enough simply to ask people to believe. May will opens the conference today with a session on Brexit, but the suspicion among MPs is that she won’t be giving much away. She is now coming under intense pressure from all sides to show her hand.

The first public shots were fired last week by the former education secretary, Nicky Morgan, an ardent pro-European with a decidedly fearless streak. Her warning that the government didn’t seem to have a plan reflects Tory Remainers’ alarm that a vacuum is being created, to be filled by all the wrong voices. The Institute for Government thinktank, which has close links with senior civil servants, has just published ‘Planning Brexit’, a report arguing that Whitehall will be hamstrung without a clear idea of what the prime minister wants and that “silence is not a strategy”. Two of the three Brexit ministers, David Davis and Liam Fox, are said to be chafing at the bit to explain themselves. If it’s hard to keep a lid on all that frustration in Westminster, it’s 10 times harder in the febrile, gossipy atmosphere of a party conference where feelings are already running high — which means this year’s fringe may be unusually lively.

May has brought a Conservative party, seemingly broken after the referendum, back together at astonishing speed, but her position is not quite as strong as she makes it look. The cracks have been papered over, not filled. On the fringe in Birmingham, exultant Eurosceptics and ex-United Kingdom Independence Party supporters newly returned to the fold will rub shoulders with those who still feel raw, robbed and in some cases significantly better qualified for high office than Fox or Davis.

And the signs are that the beleaguered modernisers aren’t going down without a fight. The lesson some have drawn from Labour’s current travails is that they can’t rely on a chaotic opposition to stop a hard Brexit, and they feel increasingly driven to act as both opposition and governing party. May can’t put off for ever spelling out her position in more detail. It would be silly to overstate the problems facing a honeymoon prime minister, swimming with the tide of popular opinion. But it would be foolish, too, to imagine that voters can give her the benefit of doubt for ever or that the strategy she employed in the Home Office of battening down the hatches and diving deep will work in Downing Street whenever there’s a crisis. Sooner or later, every submarine has to surface.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Gaby Hinsliff is a Guardian columnist and former political editor of the Observer.