Catalan separatists prepare for war of attrition against Madrid

Spain’s government will not give way on Catalonia. The next step may ruin the province or boost the rebel cause

For years there were warnings of the impending “train crash” in Catalonia, but nothing was done to prevent it. As a result, horrified Spaniards have now spent three weeks watching a slow-motion collision that became dramatically worse with the decision to impose direct rule from Madrid.

While leaders on both sides blame each other, there is growing anger at the inability of either to swallow their pride and take a step back. “Now that we are at the cliff edge, it seems that there is no option but to step over it,” Fernando Garea, a veteran commentator at El Confidencial online newspaper, wrote. “We can then continue arguing from the bottom of the gorge.”

Politics having failed, civil disobedience is pitted against the law of Madrid. Separatist leaders think they will win the confrontation because each clash between popular power and the state creates converts to their cause —which polls show had only 41 per cent backing before a chaotic referendum and police violence on October 1.

Yet a poll run by Barcelona’s El Periodico newspaper last week shows that, despite the outrage and sympathy provoked by the police charges, separatists have a long way to go before they can properly claim to represent the will of the Catalan people.

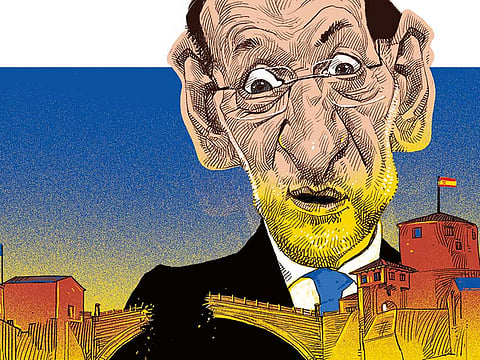

According to that poll, 55 per cent of Catalans do not think the referendum – where only 43 per cent of people cast countable votes – is a valid basis for declaring independence. Carles Puigdemont, the Catalan president, has, nevertheless, threatened to ask the regional parliament to do exactly that in response to direct rule. Since separatists have a majority there, which they used to pass the referendum law that was then struck down by the constitutional court, any vote would probably succeed. All the deputies who vote in favour – about 70 of them – could be hauled before Spanish courts. It is now clear that the conservative government of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, having won the support of EU leaders, will be implacable in its attempt to enforce the law and govern directly. It is impossible, however, to measure the appetite for further confrontation among the separatists.

Rajoy has the law on his side and the power of the state in his hands. If the separatists decide to fight, they are likely to lose many battles. That may help win sympathy as they try to argue that they are an oppressed people, but it is a tiring option for their supporters – and one which requires volunteers willing to become martyrs, facing court cases, fines, bans from public office and, possibly, prison time.

When a judge ramped up the tension further last Monday by arresting Jordi Sanchez and Jordi Cuixart, the leaders of the two principal separatist pressure groups, on sedition charges, 200,000 people protested in Barcelona’s Diagonal boulevarde. But when the two groups called on people to remove money from “unpatriotic” banks on Friday, the response appears to have been minimal.

Boycotting banks could backfire. The two biggest in Catalonia, La Caixa and Sabadell, have already moved their head offices out of the region in response to Puigdemont’s threats to declare unilateral independence. A tit-for-tat boycott of Catalan goods by consumers in the rest of Spain could provoke even more companies to leave.

Jordi Sanchez, the wily and capable head of the Catalan National Assembly group, will not be enjoying jail – where other inmates shout “Viva España!” at him – but he knows that his imprisonment has added more diehards to the cause.

Key to the separatist narrative that has been so successfully built over the past half dozen years is the idea that Catalonia, and Catalans, are victims. That was boosted on October 1 and separatists will hope that direct rule – which polls show two-thirds of Catalans oppose – increases that feeling.

Either way, they are now plotting to turn direct rule into an unworkable disaster. Reportedly regional ministers may refuse to budge from their offices, requiring police to remove them — with peaceful crowds in place to prevent that from happening. Police units sent to carry out the task would then have to decide whether force must be used to clear the way. That could produce some uneasy standoffs.

Local government officials, including parts of the Catalan police force, may refuse to collaborate or deliberately disobey orders from Madrid — but they, too, would face legal actions and fines.

Rajoy, who is notoriously cold-blooded, is likely to sit out any public service strikes and simply hope that these turn Catalan voters against independence. The separatists have a glaring weakness: their threats to declare independence unilaterally are scaring businesses away, with more than 1,200 companies having moved their registered headquarters out of Catalonia over the past two weeks. Some fear this will provoke a definitive shift in the relative economic power of Barcelona and Madrid.

“Despite the dramatic implications of this phenomenon, nobody from the Generalitat [the Catalan regional government] has bothered to explain what is happening to those who look on with concern, and sometimes anguish, at this decapitalisation of the Catalan economy,” Barcelona’s influential La Vanguardia newspaper wrote in a lacerating editorial on Saturday.

It pointed the finger at Oriol Junqueras, Puigdemont’s No 2 and leader of the Catalan Republican Left party, accusing him of refusing to face reality. “For a long time he claimed that the markets would welcome the creation of a new state with open arms,” La Vanguardia reminded him, saying that “fear of the cliff and of legal insecurity” was driving companies away.

“Does the Catalan government think that international investors are going to come to a place where the locals are leaving en masse?”

Rajoy’s party has long wanted to limit the devolution of powers in Spain, and some will see this as an underhand way of managing that. On Saturday, the speaker of the Catalan parliament, Carme Forcadell, called the measures a “de facto coup d’etat” She added: “It is an authoritarian coup inside a member state of the European Union,” adding that Rajoy intended to “put an end to a democratically elected government”.

Inaki Urkullu, the prime minister of the Basque regional government, said: “It is an extreme and disproportionate measure, which blows up bridges. The Catalan government has our support to seek a constructive future.”

The Podemos leader, Pablo Iglesias, meanwhile, saw a plot by “monarchist” parties, including the socialists. “This just shows their inability to come up with solutions and pushes Catalonia further from Spain,” he said.

Perhaps the bitterest blow to separatists has been the support shown to Rajoy by Angela Merkel, Emmanuel Macron and other European leaders.

Where the more diehard supporters of independence see repression, an authoritarian state and political prisoners, Europe’s leaders see an internal Spanish problem that must be solved within the confines of existing democratically approved law. Given that very few separatists are interested in leaving the EU, that is a devastating blow.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Giles Tremlett is a regular contributor to the Long Read. He is the author of Ghosts of Spain and Catherine of Aragon.