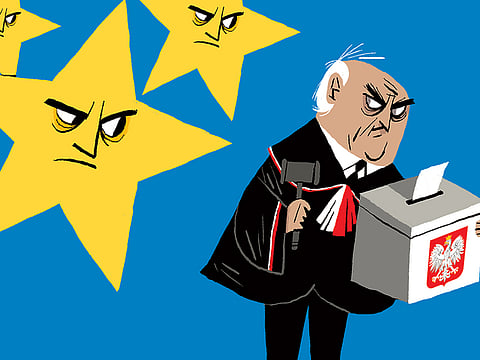

Can the EU enforce the rule of law?

As Poland illegally dismantles its Constitution, it is an affront to the European project

It’s never been easy for Americans — or for many Europeans —to understand the European Union (EU), so let me offer an analogy: Think of the United States in the years after the revolution, but before the ratification of the Constitution, when the Articles of Confederation allowed Congress to make laws but provided no executive branch or court system to carry them out. That’s the situation of the EU today.

Its members jointly agree on the rules of the group. They write and ratify treaties expressing their agreement to the rules of the group. As sovereign states, they then pledge to respect the rules of the group. But when a member state breaks the rules of the group, the group has no obvious way to stop them.

This flawed system was one of the sources of the Greek crisis that caused so much angst over the past decade. Consecutive Greek governments agreed to meet clear economic conditions before becoming part of the European currency; once they had joined, they ignored them. The ultimate result was a financial collapse, a prolonged political drama and, eventually, a bailout organised by the EU, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. But nobody felt happy about it.

The same flawed system is now confronting the different and in some ways more painful problem of Poland. Two years ago, a democratically elected Polish government, led by a party that calls itself “Law and Justice”, began illegally dismantling its own constitution. The process began with illegal appointments to the Constitutional Tribunal, and has, according to a European Commission investigation, included the passage of 13 laws designed to undermine the independence of the judiciary. This week, the Polish government signed into law a broad judicial “reform” that will, among other things, require about half of senior judges to resign and give the current minister of justice, who is also the chief prosecutor, unprecedented personal power over the selection of new ones. Among other things, the ruling party could use “its” judges to shape voting laws and even the results of elections; to prosecute political opponents; to reinforce financial pressure on independent media, which included, recently, a large fine placed on a television station that had the temerity to broadcast anti-government demonstrations.

But Poland, like Greece, also signed a series of treaties when it joined the EU, some promising to respect the rule of law, freedom of the press and judicial independence. Now the European Commission faces the same kind of turning point: Can it enforce the rules of its own club? Last Wednesday, it announced that it will try: The commission has, for the first time, invoked a procedure — Article 7 of the Lisbon Treaty — that could end by depriving Poland of voting rights in Europe.

Ironies abound. The Lisbon Treaty was actually signed in 2007 by a previous Polish president, Lech Kaczynski, who was the twin brother of the current Law and Justice party leader. At the time Kaczynski signed it, Poland was widely perceived as a model democracy; until two years ago Ukrainians, among others, were encouraged to follow the Polish example. (And here’s a declaration of interest that shows how much the current ruling party has changed: My husband was defence minister in a previous Law and Justice government, from 2005 to 2007, as well as foreign minister in the centrist Civic Platform government from 2007 to 2014.)

Inside the country, the ruling party’s cynical claim that its new laws will somehow rid Poland of the remnants of a communist-era judiciary are undermined both by statistics — the vast majority of judges were appointed after 1989 - and by its own curious personnel decisions. Among other things, the Law and Justice politician who is driving the changes, Stanislaw Piotrowicz, is himself a former communist prosecutor who was helping to jail dissidents as late as the 1980s.

But although the Polish piece of this drama is both strange and tragic, the more important debate is not the one taking place in Warsaw, but the one taking place in Brussels as well as every other European capital. For the rest of Europe’s governments, this really is a turning point: Are Europe’s member states really committed to the language of their treaties? Do they really believe in a set of shared political values? Do they have the political energy to enforce them? The decision they take will have all kinds of consequences, financial and political, not only for Poland but also for other countries.

The government of Hungary, another EU member, used subtler tactics to undermine its own judiciary, media and regulatory institutions; “far-right” or “populist” parties — by which we really mean anti-pluralist parties — have had electoral successes elsewhere, too. All of them will be watching what happens in Poland, and all of them will act accordingly. Just as Americans are now learning whether the rule of law can withstand a president who doesn’t respect it, Europeans are learning whether their system can withstand a member state that doesn’t respect it.

— Washington Post

Anne Applebaum is a columnist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author who has written extensively about Europe. She is a visiting professor of practice at the London School of Economics.