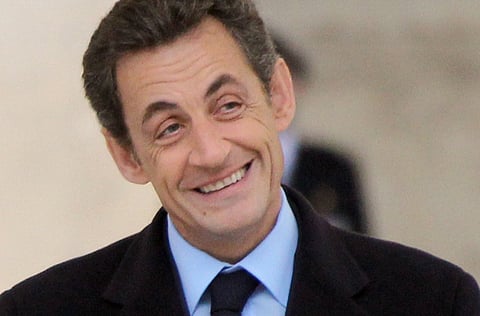

Can Hollande beat Super Sarko?

A bland socialist seems to be an unlikely opponent for the unpopular French president

After four and half years of Nicolas Sarkozy, the nation's hyperactive ‘omni-president', France woke up on Monday to find a bespectacled socialist they call Mr Normal beaming out from TV screens and news kiosks, anointed as their next head of state.

Could Francois Hollande — a 57 year-old who rides a scooter to work, looks like a provincial car salesman and has never held a ministerial post — really be the man to unseat the formidable Sarkozy in next year's presidential elections? Such is the national disillusionment with the president that every poll of recent months suggests the left-winger will do just that, and with consummate ease.

But when asked what he thought about his new, supposedly dangerous rival, ‘Super Sarko' is said to have brushed aside the threat in inimitable fashion. "Do you see this sugar cube?" he asked bemused visitors to the Elysee Palace. "It seems solid enough. Plunge it in water and see what's left. That's Hollande."

Back then, Sarkozy reportedly quipped that with his lack of government experience, Hollande was ‘not a has-been, but a never-was'.

The socialists made a daring political gamble by launching France's first US-style primaries, with the vote open to anyone willing to fork out a euro and profess left-wing sympathies. The process took too long, and the fight got dirty in the final days, but however the right tries to denigrate them as a non-event, the primaries were a resounding success. Almost three million turned out on Sunday to pick Hollande above his party rival Martine Aubry.

Despite his feigned lack of interest, Sarkozy has privately let it be known his preferred opponent would have been Aubry. The daughter of ex-European Commission chairman Jacques Delors was the architect of the 35-hour working week — a bugbear to right-wing voters.

For all his bumbling, apparently inoffensive charm, Hollande poses a worse threat to Sarkozy, as he is capable of wooing whole swathes of centre-ground and perhaps even centre-right voters prepared to plump for anyone but their current president. To reach this point, he has come a long way.

After stints working for Francois Mitterrand, the last socialist to be elected president, and Delors, Hollande took the reins of the Socialist Party in 1997. For the next 11 years, he presided over a string of regional political victories for the left but also the disaster in 2002 of seeing the socialists' presidential candidate, Lionel Jospin, knocked out by the far-right Jean-Marie Le Pen in round one.

Supporters say he kept the party together, but critics counter that the cost was inertia. But in that time, Hollande had also carefully nurtured his political power base in the cattle-breeding Correze department in central France — long the fiefdom of Gaullist ex-president Jacques Chirac — where he is now head of the county council.

While Sarkozy claimed as his urban fiefdom Neuilly-sur-Seine, France's richest suburb, Hollande seduced La France Profonde, even gaining the support of Chirac, who announced he would vote for Hollande — to Sarkozy's horror.

Corruption

To add to his armoury, Hollande has nurtured his image as a responsible socialist, careful not to promise the moon in a time of economic hardship. "If I am more popular than the others, it is not thanks to my promises but more to ones that I do not make," he said. Now all of the primary candidates, including his ex, have rallied behind him, buoyed by the fact that more French want to see a Left-wing president than at any time since 1981 — when Mitterrand was first elected. For Sarkozy, on the other hand, the situation looks grim.

Not a week goes by without some major revelation about corruption on the right, with several of the president's men either under investigation or facing serious allegations of bending or breaking the rules. Judges are probing claims that L'Oreal billionaire heiress Liliane Bettencourt illegally financed Sarkozy's party.

The allegations have been seen as making a mockery of Sarkozy's pledge to build an ‘irreproachable republic;'. But what the French really hold against him has been his lack of economic results, analysts say. Elected to help the country to ‘work more to earn more', the president has failed to deliver on key promises to boost spending power.

On Wednesday his camp began the counterattack with a convention to dissect Hollande's plans. They should find plenty of ammunition, as it envisages a return to a retirement age of 60; scrapping euros 50 billion (Dh253 billion) in tax exemptions; financial penalties for those that lay off staff while in profit and the creation of 300,000 public sector jobs for the young.

With pressure from ratings agencies on France to make even more cuts in public spending, Sarkozy may well argue the country stands to lose its triple A status under a socialist president. "The hour of truth has come. The primaries were a flurry of false promises and irresponsible spending," said budget minister Valerie Pecresse. "Now it's time to settle the accounts. The bill will be socially and economically unbearable for the French."

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2011