Britain breaches ‘peak Brexit confusion’

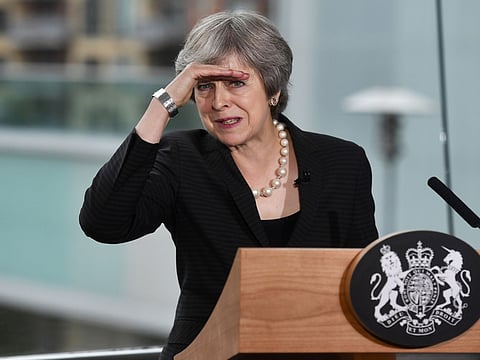

Besieged on multiple domestic and international fronts, Prime Minister May’s hold on power is very fragile

With parliament going into summer recess tomorrow, Britain last week reached ‘peak Brexit confusion’. This comes after a tumultuous time for Prime Minister Theresa May, leaving her very vulnerable in Downing Street again, after Cabinet resignations; the diplomatic disaster that was United States President Donald Trump’s trip; and the government’s bizarre handling of legislation detailing Britain’s scheduled exit from the European Union.

Almost two years to the day that May took office as prime minister, the government at the end of last week sought to draw a line in the sand with publication of its Brexit White Paper. Yet, May’s vision, embodied in the document, is unlikely to be the last word after already coming under criticism from the UK political Right and Left, Brussels, not to mention the extraordinary interventions of Trump. This move to define the UK’s final negotiating position follows a nationwide debate about what the meaning of the 2016 referendum result was. For contrary to what many Brexiteers now insist, the Leave vote encapsulated a range of sentiment and there is still not a consensus behind any specific version of Brexit, whether hard or soft, disorderly or orderly, which makes May’s task enormously difficult.

However, decision time is fast approaching. For the UK Government now has — under current timelines — less than nine months to deliver on a final Brexit framework settlement.

After the resignations of foreign secretary Boris Johnson and Brexit secretary David Davis week before last, the White Paper sets out a preferred pathway forward by the prime minister (a Remainer in the 2016 referendum). Her clear view is that immigration and sovereignty were the primary drivers behind the Leave campaign’s victory two years ago.

From this perspective, it follows in the White Paper that better controlling EU migration flows and seeking to end the jurisdiction in the UK of the European Court of Justice should be key objectives for final-stage negotiations. Given the EU’s commitment to the free movement of goods, people, services, and capital, May has sought to strike a Brexit balancing act between delivering on these objectives, while seeking to avoid the hardest of hard Brexits favoured by some in her Conservative Party.

May’s vision will see the UK, in her words, discard all “bits of the EU”. This includes membership of the 500 million-consumer European Single Market, full membership of the EU Customs Union, the Common Commercial Policy and the Common Commercial Tariff.

A central challenge in her politically weakened position is that May is now being confronted on multiple fronts. From the Right, Brexiteers like Johnson and Jacob Rees-Mogg argue that the compromises with Brussels in the White Paper are already a step too far (and this despite the fact that the EU said Friday it will still need to see significant further changes in the UK negotiating stance to get a deal) and that they would rather now see a hard, disorderly Brexit that will see no final settlement with the EU than what she proposes in the White Paper.

In parliament last week, Rees-Mogg tabled a series of Brexit legislative amendments that seemed to contradict the spirit if not the letter of the White Paper. Yet, after the government initially criticised these, it did an extraordinary volte face to accept them underlining the weakness of May’s position and creating further confusion about the UK’s negotiating stance.

Diverse and divergent views

Conversely, many who supported Remain in the referendum tend to favour a softer Brexit than May, potentially combined with a referendum on the terms of any exit deal that is ultimately agreed with the EU-27. From this perspective, the prime minister’s Brexit narrative (let alone that of harderliners like Johnson and Rees-Mogg) about the referendum’s meaning is far from the full picture, and there were, in fact, diverse and sometimes divergent views expressed by people voting to exit the EU in 2016. Some Leave voters, for instance, of an isolationist bent, focused on perceived costs and constraints of EU membership other than immigration and sovereignty. Meanwhile, a significant slice of the electorate voted Leave as a protest against non-EU issues such as the domestic austerity measures implemented by UK Governments since the 2008-2009 international financial crisis.

Many of these voters were fixated by the issue of UK financial contributions to the EU’s budget. They were also taken in by the spurious promises that all the membership money currently paid to Brussels would, post-Brexit, be entirely pumped back into UK public spending, especially the health service.

However, other Leavers voted in 2016 for an alternative vision of a buccaneering global UK that could, post-Brexit, allow the nation to secure new ties with countries outside the EU. It is many of these people who now want to see, for instance, new trade deals with key Asian markets such as China and India; the Gulf states; and mature markets such as the US, Canada and Australia.

Yet, in his visit to the UK week before last, Trump undermined May by appearing to question whether a new US-UK trade deal is possible under her preferred Brexit approach, contrary to what the prime minister has asserted. Trump’s intervention has given succour to hard Brexiteers in May’s party, especially after he praised Johnson who may well launch in the coming months a leadership challenge to her.

Taken overall, May’s White Paper is unlikely to be the final word on Brexit. Besieged on multiple domestic and international fronts, her hold on power is very fragile and it remains possible she could be unseated from Downing Street before Britain’s scheduled exit from EU next March.

Andrew Hammond is an associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.