America won’t go to war with North Korea on purpose, but it might by accident

The Cuban missile crisis in the past and other recent conflicts demonstrate that the road to war seldom runs through an informed assessment of facts on the ground

In the midst of the vitriol flying between Washington and Pyongyang, a number of voices have emerged to assure the world that war is indeed unlikely. The leadership of both nations, they explain, has many rational, well-informed actors who recognise the potentially catastrophic consequences of a second Korean War, and hence will avoid crossing any of the critical lines that might take us there.

Theoretically, the voices are correct. Unfortunately, modern history shows that decisions for war are not made in theoretical circumstances, nor rooted in rational calculation. They are instead made by flawed individuals driven by emotion, miscalculation and misperception, and influenced by others with their own agendas who sit far from the chain of command.

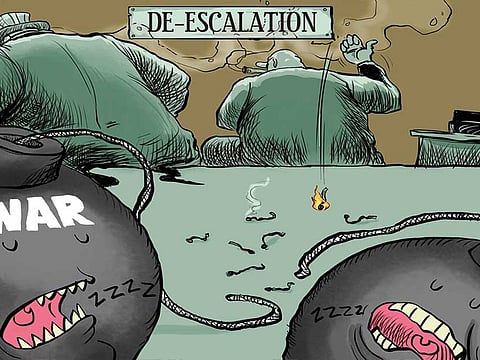

The great danger of the current crisis is thus not that decision-makers in Washington and Pyongyang will deliberately weigh the costs and benefits of another Korean War and decide it is worth pursuing. It is instead that a sudden and unexpected moment triggers a hasty and emotional decision that leads both sides down a tragic path from which there is no return.

The 1962 Cuban missile crisis demonstrates how easily foreign policy crises can spin out of control despite the best intentions of those at the top of the decision-making process. Most Americans celebrate the wisdom demonstrated by former United States president John F. Kennedy and former premier of the erstwhile Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev, who acted with restraint while working to avoid what surely would have been a devastating clash. Few Americans, however, understand how close to war the US actually came despite their efforts, as the actions of less well-known figures and the inevitable chaos of unanticipated circumstances threatened to undermine their best intentions.

On October 27, 1962, Soviet forces shot down an American U-2 over Cuba, killing the pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson. Khrushchev had given specific orders not to fire on American targets unless war had started, but the Soviet commander on the ground, General Stepan Naumovich Grechko, decided to shoot it down on his own authority. American officials had earlier agreed that such an action would probably evoke an American military response against Cuba, but Kennedy wisely chose to delay such a response.

That same day, American ships were harassing a Soviet submarine in the Caribbean. With no contact from Moscow and unsure of the current status of events on land, the captain, Valentin Grigorievitch Savitsky, ordered the launch of a nuclear torpedo. Only the opposition of his second-in-command prevented an act that surely would have sparked massive retaliation.

In the end, the Cuban crisis was resolved peacefully. But the fact that the world came perilously close to a nuclear conflict, because of actions taken by individuals outside of the world’s capitals and based on erroneous assumptions, should be a sobering warning for those who minimise the current dangers.

The path to other recent conflicts also demonstrates that the road to war seldom runs through an informed assessment of facts on the ground. In June 1950, North Korean forces swept over the 38th parallel, sparking the Korean War. Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin had earlier rejected Kim Il-sung’s request to launch an attack against the South. But he soon changed his mind, in no small part because of a mistaken belief that the US would probably not intervene, and because of Kim Il-sung’s unmerited assurances that massive indigenous backing from the South would ensure a quick victory before former US president Harry Truman could react if he chose to do so.

Likewise, the American role in the Vietnam War exploded after the alleged second Gulf of Tonkin attack on August 4, 1964. We know now that this attack never occurred, but American military and political leaders believed that it had, and former US president Lyndon Johnson used it as an excuse to obtain the functional equivalent of a declaration of war. In neither of these cases were the critical decisions for war made as part of a sober and thorough assessment of accurate evidence. And yet, war came nonetheless.

The current standoff in Korea seems particularly ripe for such an unintended conflict. A long history of rivalry has predisposed each side to read the worst possible motives into the other’s actions. Official lines of communication between the two are virtually nonexistent; at the moment, the US doesn’t even have an ambassador in South Korea. The two leaders are inexperienced and emotional, with a tendency to personalise strategic matters and unleash bellicose rhetoric that just heightens tensions throughout the region. North Korean defectors warn of Kim Jong-un’s desperate and unyielding commitment to his nuclear programme, which he sees as critical to the preservation of his regime, and of the growing doubts about his government at home. And the North has launched a number of limited but deadly military operations against the US and South Korea over the past decades, ranging from the attack on the USS Pueblo in 1968 to the attack on the Cheonan in 2010, but has never faced serious retribution for them, probably encouraging Kim Jong to trust in the safety of a limited strike that could be a critical first step.

Recent history thus suggests that the greatest danger that America now faces is not that President Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un will decide to go to war, but that isolated individuals who most have never heard of, operating within the inevitable chain of mistakes and miscalculations that are the by-product of human weakness and exigent circumstances, will decide for them. This concern seemed particularly acute last week, as the US and South Korea held their annual Ulchi Freedom Guardian drills, which for the first time included a nuclear war game and which the North has condemned for “adding fuel to the fire”. “No one can guarantee that the exercise won’t evolve into actual fighting,” they noted ominously.

The lessons of history suggest that under such circumstances, policy-makers on both sides cannot just rely on good intentions. They need instead to be cognizant at all times of the heightened risks inherent in such situations, act with significant restraint at even the slightest alleged provocation and impose institutional checks at every level to prevent a small misstep from spiralling out of anyone’s control.

— Washington Post

Mitchell Lerner is associate professor of History and director of the Institute for Korean Studies at the Ohio State University. He is also associate editor of the Journal of American-East Asian Relations.