Warfare by drone still counts as warfare

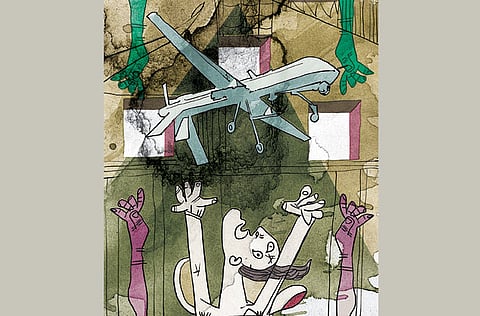

The War on Terrorism’s unfortunate contribution to history has been the drone

The most famous painting of the 20th century, Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, commemorates the bombing of the small Spanish town on April 26, 1937, by the German Air Force, in support of General Francisco Franco’s fascists in the Spanish Civil War. Hard to believe, but this was history’s first extensive bombing of a civilian population. In his book Postwar, the late historian Tony Judt pointed out that more civilians died in Second World War of various causes than did soldiers. That was not true of First World War or most earlier conflicts. Guernica was a German dress rehearsal for the London blitz, the destruction of Warsaw and so on. Soon to come on the Allies’ side were the destruction of Dresden, the firebombing of Tokyo and of course the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Today, when we think of war, bombing from the sky is one of the first images that come to mind. One consequence of this and other developments in warfare has been a blurring of the distinction between soldiers and noncombatants. Wars used to be conducted on battlefields, between soldiers in uniforms lined up in rows, bayonets ready. People famously took picnic baskets to watch the first battle of Manassas, thinking that the Civil War would be like that. It was not.

The War on Terrorism’s contribution to this unfortunate history has been the drone: An unmanned plane that can aim at and hit a target with enormous precision. And, as with earlier developments, the world is getting used to it. The eye passes right over headlines such as ‘Yemen: Drone Strike Kills 2’ buried inside the newspaper. Right now, the US has, more or less, a monopoly on drones, which will not last any longer than its monopoly on nuclear weapons did. The advantages of using drones are obvious. No American lives are put at risk and the precision minimises collateral damage, including the deaths of innocents who happen to be nearby. The disadvantages follow from advantages. When a military option seems less painful, it is more likely to be resorted to. The ability to strike at the enemy with absolutely zero risk to your own people must be especially appealing to politicians such as President Barack Obama, for whom the decision to put Americans in harm’s way is surely the toughest one to make. However, drones also highlight a terrible anomaly of civil-libertarian societies: The contrast between how we treat killing — state-sponsored killing — in battle and how we treat killing in civilian life. There are no Miranda warnings in the trenches. In fact, the entire edifice of protections against convicting the innocent is irrelevant in battle. You kill the other guy because he is trying to kill you and unless you are raping women or slaying babies, you are going to get a medal, not criticism.

Collateral damage — including the deaths of complete innocents — comes with the territory. Once upon a time, these two spheres were separate, with one set of rules for the battlefield and one for normal times and places. Now, every place is a battlefield. The World Trade Centre, for example. Why is it not only OK but praiseworthy for the US government to aim at Anwar Al Awlaki and kill him because he is an Al Qaida “operative” who may not actually have killed anyone directly (though no doubt he would have liked to), while Adam Lanza, who shot and killed 20 schoolchildren and seven adults, including his mother, before killing himself, could have had a trial that lasted weeks and cost millions of taxpayer dollars? What about the other person riding in Al Awlaki’s car, who was killed with him? What about Al Awlaki’s 16-year-old son, who died in a drone attack two weeks later? Al Awlaki was a US citizen and his child was born in Colorado, if that makes any difference.

The Obama administration’s position is that it has looked at this carefully and there is no legal problem with drone assassinations for reasons that regrettably must remain secret. US District Judge Colleen McMahon’s wonderfully acerbic decision, issued last week, reluctantly acknowledges the administration’s right to maintain this absurd position. A “thicket of laws and precedents,” she wrote, “effectively allow the Executive Branch of our government to proclaim as perfectly lawful certain actions that seem on their face incompatible with our constitution and laws, while keeping the reasons for their conclusions a secret.” As is so often the case, Stalin may have said it best (if, indeed, he really said it): “One death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic.” The deaths of Al Awlaki and Lanza may not be tragedies, but the differences in how we think about them deserve better than a “because we said so” — especially from a liberal Democratic administration led by a former president of the Harvard Law Review. I wonder especially about the teenage son killed in a separate drone attack and the two killed just before New Year’s Eve because, according to Reuters, they were “suspected of being insurgents linked to Al Qaida.” Is that good enough for you?

— Washington Post

Michael Kinsley is a Bloomberg View columnist.