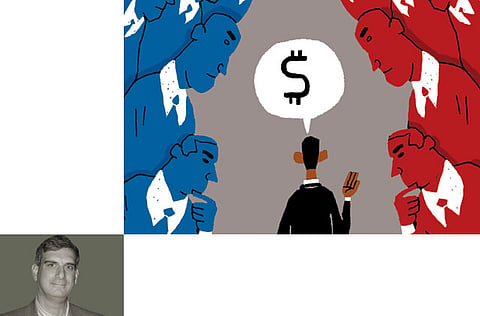

US default will have a domino effect

Politicians bickering about the debt ceiling must understand that a financial meltdown will have global repercussions

A financial train wreck looms. Exactly how America got itself — and potentially everyone else — into this mess is the story of how a routine legislative chore became the latest victim of Washington's dysfunctional political culture. I am talking, of course, about the debt ceiling — a quirk of America's political system and its division of executive and legislative powers.

The president runs the American government, but cannot spend any money unless he gets approval from Congress. That means the Treasury cannot sell bonds or even pay the interest on bonds it has already sold without the legislature's permission.

Congress, never eager to give any president a blank cheque, has traditionally fixed an upper limit to the amount of debt the country can float. Regardless of who controls Congress this limit has routinely been raised whenever the government nudges up against it.

Congress does this because the status of the dollar as the world's reserve currency and the universal understanding that US Treasury Bills are the safest investment on earth are key attributes of American power — as important, in their own way, to the US' role in the world as its military.

Everyone in Washington knows this, and accepts that periodically voting to increase the debt limit is an annoying but necessary duty of governing.

Until now, that is.

Since last spring, Republicans have let it be known that they will not agree to an increase in America's borrowing limit unless the measure is accompanied by huge budget cuts. Because such cuts would fall most heavily on social services, Democrats have alternated between refusing such demands outright and insisting that any cuts must be accompanied by at least some rise in taxes, something the GOP flatly refuses to contemplate.

So far this all sounds pretty normal. Unfortunately, it is not. Previous debt ceiling increases have, occasionally, been tied to spending cuts or tax increases. But holding America's ‘full faith and credit' (to use the official term) hostage to a sweeping multi-year deal that fundamentally alters the entire government's budget priorities? That is new.

Complex challenge

What is genuinely scary is the sense that the current debate is increasingly controlled by people who do not know what they are talking about. In particular, a number of Republicans in the House appear to believe their own simplistic talking points (example: ‘the government has to balance its budget just like a family sitting around their kitchen table.' Actually, no. The government's budget is absolutely nothing like a family budget).

Several Republicans have said they will only consider — not agree to, but merely consider — voting to raise the debt limit if their entire fiscal agenda is enacted first, including amendments to the constitution requiring all budgets to be balanced and a two-thirds majority to raise any tax. This displays both a maximalist mentality that rejects the very legitimacy of democratic give-and-take, and a stunning ignorance of the procedures required to amend the US Constitution.

Amending the constitution is a lengthy, complex process. It cannot be done in the three weeks that remain before the federal government loses the ability to pay its bills.

In a normal legislature this is the moment when party leaders step in, cut a reasonable deal with the other side and then lower the boom on junior members to ensure that the deal is enacted. At the moment, however, House Speaker John Boehner appears to be guided by his freshmen, not the other way around.

The situation is made worse by the fact that several of the Republicans currently running for the presidency (including several who surely know better) are publically siding with Tea Party know-nothings who contend that letting America go into default is no big deal.

If this all sounds arcane and far away rest assured it is not. Because American government debt has long been considered the safest investment on the planet it is held in large amounts by banks, governments and investment funds in every corner of the globe.

There is a chance, of course, that the doomsayers are wrong and that a US default would not trigger a global financial apocalypse. It is, however, a microscopically remote chance — one that no sensible statesman would want to take.

Even Ronald Reagan, the iconic leader of modern American conservatism, recognised this. Back in 1983 he rejected calls in his own party to ignore the debt ceiling, warning of "incalculable damage" if America failed to meet its financial obligations even briefly.

With the clock ticking the conventional wisdom is that some sort of deal will emerge at the last second, much as was the case earlier this year when Democrats and Republicans averted a government shutdown by barely an hour.

What American leaders need to remember is that a government shutdown is embarrassing and inconvenient, but a default — even a short-term technical one that is quickly ‘fixed' — may ricochet through the world economy with unpredictable consequences for years to come.

All of us, therefore, need to keep an eye on Washington in the coming weeks and hope that, for once, short-term thinking takes a back seat to doing what needs to be done.

Gordon Robison teaches political science at the University of Vermont.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox